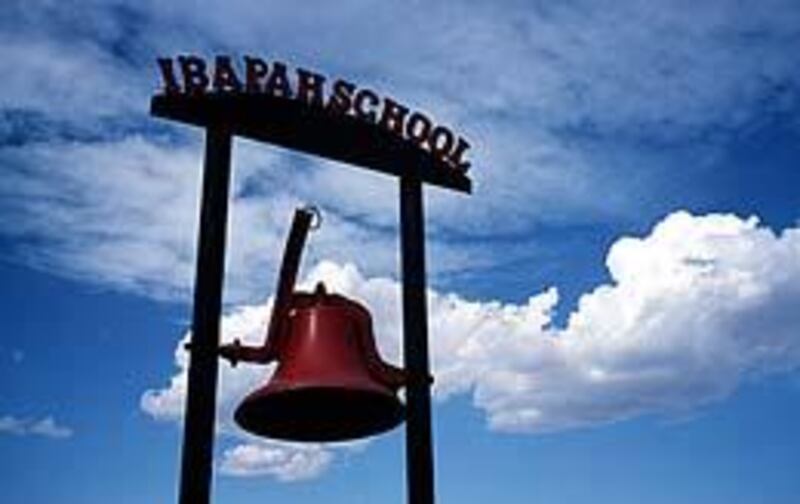

IBAPAH, Tooele County — Milton Hooper of the Confederated Band of Goshutes looks out over Spring Creek — a stream the elders of his tribe call "Fish Springs."

"I like it out here," Hooper said. "Out here you can actually hear yourself think."

Just to the west is the Nevada border. Several miles north is Wendover. But where Hooper stands, it's all Goshute country, the Deep Creek Reservation, which straddles the Utah-Nevada border.

Hooper is checking for cutthroat trout, a breed of fish anglers call "natives." The Confederated Goshutes are trying to increase the scope and number of those natives. And, along the way, they hope to do the same for themselves, the "natives" of Utah.

"Conservation is a big part of what we are about," said Hooper, leaving the door open for interpretation. Is he talking about conservation of wild life? The land? His culture? His people?

Yes.

About 100 miles east of Ibapah, the Skull Valley Goshutes have their own brand of landscape. The mountains ring the valley there like the pinched crust of an apple pie. But these days, the vista also includes foreboding fences, barking dogs and "No Trespassing" signs. Ever since the Skull Valley Band began talking about storing radioactive waste, it has been on the defensive. The media, environmentalists, politicians and corporate executives have all descended on the area in a swarm.

In an ironic twist to an old John Ford Western, this time the Indians appear to be pinned down in the fort while hostile forces come at them on all sides.

And they're fighting back.

At the little Pony Express convenience store on the reservation, for instance, a woman is asked if the Skull Valley Band and the Confederated Band ever join together for events. She snaps, "Why? Because we're Indians? Do you associate with every white person?"

In Skull Valley these days, most words are fightin' words.

Still, despite the difference in the tone and situations, the history of the two bands of Goshutes does blend. For in essence, Hooper says, the two groups aren't two groups at all. He says the "Euro-American pioneers" simply made distinctions where the Indians themselves never did.

"All Goshutes are basically Western Shoshone," he said. "Back in the 1930s, when the Indian census was taken, we had various extended families in different parts of the region. They were eventually subdivided into separate groups, but we're really just part of the same large family."

In other words, the Goshutes, Shoshones and Paiutes are actually family clans, not distinct nations.

Today, no one can be sure just how long the Goshute people have inhabited Utah's arid west desert. Like most tribes, the Goshutes themselves believe they have been there since the beginning of time. Some anthropologists speculate the tribe may have migrated from the Death Valley region of California, which would explain the amazing survival skills of the people. After Death Valley, the Utah desert can feel like a garden spot.

One thing is known, however. The name of the tribe, Goshute, comes from a native word that means "people of the desert." And to survive, they became excellent amateur botanists, recognizing which roots and leaves were edible, which were not. They wore rabbit hides for protection and developed a taste for roasted grasshoppers. Because of the way they lived, the Goshutes were often ridiculed as "Digger Utes" by the first settlers and became the object of jokes in frontier rags like the magazine "Keepapichinin" (Keep-a-pitching-in).

"The scarcity of resources in the arid Goshute homeland was a primary contributor to scarcity in other areas of Goshute life," Dennis R. Defa writes. In short, the tribe has few ceremonies, and there is not an abundance of handicrafts and ornamental designs. For the Goshutes, survival has been the order of almost every day. It has all been hunting and gathering.

Today, mainstream attitudes about the Goshutes are changing. More and more, the tribe is admired for carving out a legacy in the wilderness. The Goshutes are viewed as resilient and resourceful. And the hard-scrabble life that made them so self-sufficient and independent shows up in their attitudes and — vital to Utah — also their politics.

To understand why the Skull Valley Goshutes have been at the center of so much political and environmental turmoil recently means returning to a document that sent the two bands of Goshutes in different directions: The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

By the 1930s, Indian populations and land in Utah were shrinking alarmingly, partly because of missteps by federal agencies. The Utes, for instance, had lost about 90 percent of their territory. So the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 was written to undo government wrongs and keep the tribes away from two-legged predators. By signing the act, tribes were allowed to form their own governments, collect taxes and hold courts. They also received help with their schools and health care. In return, the tribes agreed to allow the Bureau of Indian Affairs to monitor their activities and offer federal input.

The Skull Valley Goshutes, however — much like conservative Republicans — were suspicious of big government. They felt allowing the government too much access would lead to abuses. And being the independent — some would say headstrong — people they were, they simply refused to sign the document.

And that defiant stance made all the difference and led to the current state of affairs.

It once led, for instance, to the Skull Valley Goshutes, in need of income, leasing land to Hercules for rocket testing and currently has led the band to flirt with storing radioactive materials.

It has led to officials of the U.S. and Utah governments being forced to stand by and wring their hands while the Skull Valley Goshutes wrangle over tribal leadership — even to the point of candidates coming to blows, as they did last fall. The BIA has no say.

And since the Skull Valley band has no charter or constitution, it has also led to a dozen interpretations of tribal law, history and election results.

Today, two different administrations claim to have a mandate to lead the band, one faction linked to pro-nuclear leader Leon Bear and the other linked to Rex Allen, who is softer on the issue. But since the backlog of unsigned paperwork was getting so immense, in October David Allison, a superintendent with the BIA, said the federal government needed someone with whom to deal.

"There is some business we can't ignore," Allison said at the time. "We had to make a move. It's simply for our purposes at this time."

The government chose to deal with Leon Bear. And that BIA move seems to have quieted the political firefight for a time. What effect it will have on the future of the tribe, however, is another matter. Many observers share the impressions of Forrest Cuch, director of the Utah State Division of Indian Affairs.

"I don't think anyone has made any earnest gesture to really help them as a people," Cuch said, pointing out that few people have been dealing in good faith — everyone inside and outside the band has an agenda.

Meanwhile, in Ibapah, the Confederated Band of Goshutes has watched the nuclear drama unfold with interest but has generally kept its own counsel. It would rather not be stirred into the mix.

"Out here, we're pretty much overlooked," Hooper said.

And he doesn't say it in a complaining voice.

"People get us mixed up with the Skull Valley Goshutes," said Amos Murphy, chairman of the Confederated Band. "But we try to stay out of the issues of Skull Valley. We have some beautiful land and resources here, and we're working to excel economically. We'd like to bring more people to our valley to see what we have."

In short, life in Ibapah is much as it has always been: open and simple, with people taking a quiet pride in their past. The children at the school recently produced a stunning picture book about a tribal legend called "Pia Toya" (see story above). Currently, they are planning to do a second book about preserving those cutthroat trout at Fish Springs.

The working title for the book? "Preserving the Natives."

The Ibapah Goshutes are well aware of what they have and what they don't have.

"I like the fact that when I go home I can ride 10 or 15 miles without opening any gates," said Marilyn Linares, a teacher at the school who grew up in Ibapah. "The only thing you hear at night out here are the crickets. I taught for a couple of years in Tooele, but I came back home. This is the best place in the world."

Given the whirlwind of politics swirling through Skull Valley these days, one suspects the Goshute "cousins" living there must feel just a bit envious of life in Ibapah.

E-mail: jerjohn@desnews.com