A hard lesson: Even heroes die

Utahn who tried to stop Challenger launch

First published in the Deseret News on Jan. 25, 2001, in observance of the 15th anniversary of the Challenger explosion.

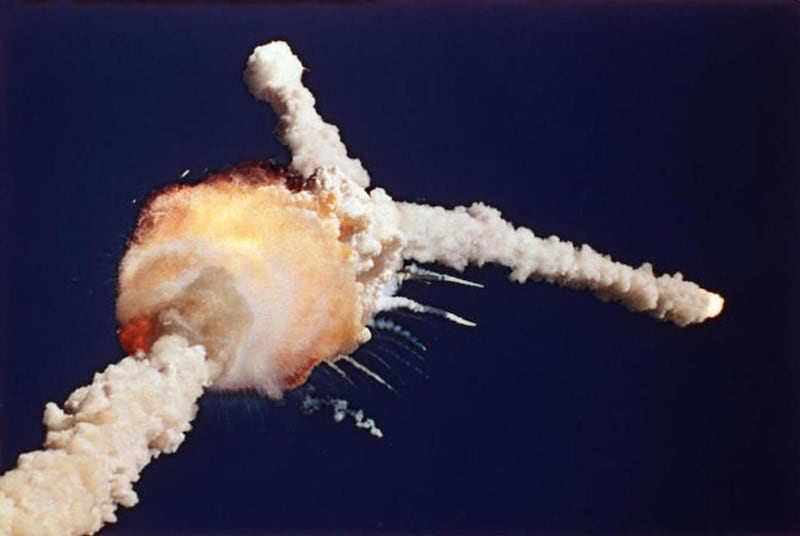

Fifteen years ago Sunday, millions of Americans were horrified by the worst accident ever to strike the nation's space program, the fiery destruction of the space shuttle Challenger.

The explosion 73 seconds after launch ended the lives of all seven members of the crew: the commander, Francis "Dick" Scobee; co-pilot Michael Smith; Ellison Onizuka; Ronald McNair; Judith Resnik; Gregory Jarvis; and Sharon Christa McAuliffe, who was to be the first "teacher in space."

For a time, shuttle launches had become nearly routine. The space shuttle was seen as NASA's workhorse, and the public had begun to expect flawless expeditions. The accident altered that expectation, probably forever.

An investigation by a presidential commission found that the accident was caused by hot propellant gases from the right solid-fuel booster rocket leaking from a joint and igniting the shuttle's external fuel tank. The failure of an O-ring sealant device in the booster had allowed the leak.

The boosters are manufactured by Thiokol, a Utah company with a production line near Corinne, Box Elder County. The company employs about 3,400 people.

The disaster was especially terrifying to school students, many thousands of whom watched the launch live to see a teacher go into space. But it also stunned the public at large, Thiokol and NASA.

For two years and eight months, the remaining shuttle fleet was grounded as the agency and industry looked for ways to make the program safer. NASA abandoned the "teacher in space" program and other offshoots featuring civilians in orbit.

The shock wave was so enormous that it might have derailed the space program. But when the space shuttle Atlantis launched on Sept. 29, 1988, with a satellite-detection system aboard, the spacecraft and its boosters had been reconfigured from stem to stern. About 200 improvements were made to various systems.

Shortly after the Challenger accident, Thiokol and NASA carried out a major redesign to the solid rocket motors, assuring redundancy in the field joints that involved the O-ring failure. Thiokol continues to test its motors every year in static ground firings, making sure they meet standards, said Thiokol's Gerald Smith, vice president and manager for space operations.

The procedure "just gives us added confidence," he said.

Kristen W. Larson, spokeswoman at NASA's Washington, D.C., headquarters, said part of Challenger's legacy is that it "reminded us that, even though it seemed at the time that space shuttle flight (was) routine . . . space really is a very risky environment."

The agency made significant changes in response to the Challenger accident, she said. Hardware and the boosters were improved. "We also did some changes to how the programs are managed."

In January 1986, Challenger sat through repeated delays. Finally, it was launched despite the protests of some Thiokol engineers who believed cold weather at Cape Canaveral might have made the O rings too brittle.

To prevent future mistakes like that, current or former astronauts now are part of NASA's management decision-making structure.

"We also put in place a safety organization," Larson said. The group is called Safety and Mission Assurance, and the person in charge reports directly to the NASA administrator.

Even though Safety and Mission Assurance is part of NASA, it is charged with looking at programs critically, making sure they are safe. "With the Challenger accident, there's been a real re-emphasis on safety," she said.

"There's really been a culture shift to where safety is our first priority," Larson said.

In the fall of 1998, the shuttle program was grounded for about two months because of a problem with wiring during a launch. That spacecraft orbited and returned to Earth without danger to the crew, she said, "but when we got that vehicle back to Earth we basically went through and found out that we might have a widespread problem with our wiring."

NASA fixed all the wiring problems and developed new maintenance protocols that are designed to prevent damage through such errors as maintenance platforms abrading wires.

Most recently, Atlantis was set to launch on Jan. 19, but NASA technicians noticed what might be wiring problems, possibly from the manufacturing process. So the launch was delayed until no earlier than Feb. 5.

"We certainly don't feel any pressure to launch," Larson said.

Among NASA's near-term goals is to upgrade the shuttle, with a "glass cockpit" design that is heavy on digital displays and better auxiliary power units.

A change to the main engine is also contemplated. NASA is looking at installing new monitors that would "help us detect situations in advance that might create a problem."

With Thiokol's boosters, "we are looking at redesigning several valves, filters and seals in the solid rocket boosters to help increase their reliability," she said.

NASA has recovered from the Challenger accident and is pressing on with exploring space. Ambitious unmanned explorations are planned for distant targets, with unmanned spacecraft headed to or already at Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, an asteroid and a comet.

Today's manned expeditions focus on building the International Space Station, the greatest structure ever to orbit Earth. In the permanently staffed stations, astronauts and cosmonauts will live and work for weeks or months at a time.

One project NASA is considering is a crew-return vehicle to serve as a safety backup for the International Space Station. The lifeboat would remain moored to the station unless needed during an emergency.

"Up to seven astronauts could climb into the vehicle and return safely home and land at any number of landing sites around the globe," she said.

Further down the road, "we're hoping to get out of low Earth orbit, to go to another planet or an asteroid."

One possibility is to eventually resurrect moon landings, this time to build a base on Earth's satellite.

Meanwhile, NASA and private industry partners are pressing ahead with the development of reusable space vehicles that eventually could replace the shuttle, such as the VentureStar space plane.

"The shuttle, although it first flew in the '80s, dates back to the 1970s," Larson said. "It's a great, reliable workhorse, but we've never stopped hoping to develop other vehicles as well."

Morale at Thiokol today is "quite high," Smith said. Compared with the dark days of 15 years ago. "It's just orders of magnitude different."

Workers and managers are proud of the successful launches that have taken place since then. Challenger was the shuttle's 25th launch, and Thiokol has put the space shuttle into orbit 76 times since.

A 100 percent guarantee of success isn't possible with a vehicle as complex as the shuttle, Smith said. But Thiokol is careful to assess the risks and make sure that the crew is not placed in undue danger.

"We do that through formal review processes," he noted. "We've learned a great deal over the years."

When a booster is recovered following a launch, it's returned to Thiokol's Clearfield operations.

"We systematically take it apart and we inspect it," he said. Any problem that shows up, Thiokol learns from and corrects, he said.

In the past few years, Thiokol has found "very few" flight anomalies.

With the improvements, Smith added, "I believe we're going to be flying another 15 or 20 years, for sure."

E-MAIL: bau@desnews.com