To use the Gracie Allen-type of "illogical logic" appropriate to the subject, all of a sudden we didn't notice that comedy teams weren't there anymore.

Comedy teams had been a part of American lives for decades, as pointed out by Lawrence J. Epstein in "Mixed Nuts: America's Love Affair With Comedy Teams From Burns and Allen to Belushi and Aykroyd" (Public Affairs, 293 pages, $26). But by the 1960s they had mostly faded from the entertainment scene.

Epstein tracks the history of comedy teams, from their birth in the late 1880s with Weber and Fields — "the first genuine team stars" — to their lingering death throes in the "temporary teams," such as Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder in the 1970s and '80s.

In doing so, Epstein, who earlier authored "The Haunted Smile: The Story of Jewish Comedians in America," says he found a "deeper social history of American life embedded in their story."

In seeking to determine why certain teams were popular at certain times, he concludes "that the teams flourished when we most needed a communal spirit and when we most forcefully embraced the virtues of self-sacrifice." That is, from the late 1920s to the early 1950s. "In this sense, the story of the rise and fall of comedy teams emerges as a metaphor for the struggle Americans undergo between communal responsibilities and personal desires."

The author employs a lot of that sort of psychological and sociological analysis, and much of it is convincing, though occasionally it tends to overreach into higher-intellectual twaddle: The revolt against suburban life "was the shriek of an ego released from history's penitentiary."

In general, though, his analyses are as insightful as his facts are diverting. Did you know, for instance, that the straight man has always been considered more important than the comic? He controls the pacing and other action. Consequently, his (or, rarely, her) name invariably came first, and he was often better paid.

Gracie Allen, by the way, was originally the "straight man" to her husband, George Burns. Their association illustrates perfectly, Epstein says, the dynamics of the straight man-comic team. The audience yearns for their "created world," which is held together by the tension between the "rationality" of the straight man and the fantasy of the comic.

Like Burns and Allen, most teams, before and later, were smart-dumb (Abbott and Costello, Martin and Lewis), but not Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. Nor were they straight man-comics.

Laurel and Hardy were the first enduring film team, and, Epstein asserts, possibly the best team ever, in large part because "they created the model of two friends struggling against the world." Like other great teams, they draw us into their world. And they were the only silent team to find success in sound.

Besides the Marx Brothers, other 1930s teams are little remembered. Bert Wheeler and Robert Woolsey, who had offered a precursor to Bud Abbott and Lou Costello's "Who's on First?" routine, didn't adapt to the times, which were turning to optimistic films, as did the Marx Brothers.

By the 1940s, teams were already past their peak, except for the Three Stooges, who never broke up and never lost their audience. Interestingly, the Stooges made the first American anti-Hitler film, "You Nazty Spy!," released in January 1940, a brave move when Hollywood was still concerned about overseas sales.

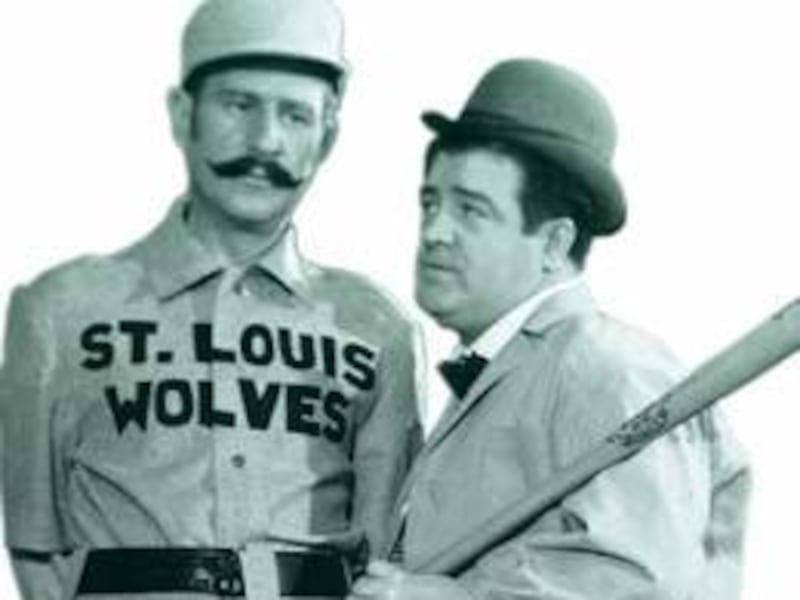

Abbott and Costello, who dominated comedy in the 1940s, were a throwback to the straight man-comic form. Jerry Seinfeld called them a vaudeville and burlesque preservation society. Epstein considers Abbott to have been the best straight man ever.

Such "temporary teams" as Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, Epstein maintains, portended the coming decline of teams. They were echoed years later by similar temporary teams in the new medium of television — Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca, Jackie Gleason and Art Carney, Lucille Ball and Vivian Vance.

Occasionally, Epstein strays from his main topic into other areas — the controversy over "Amos 'n' Andy," radio comedy in general, and the social effects of television. But none of this detracts from his narrative. To the contrary, it adds to it.

The disappearance of comedy teams is attributed by Epstein to changes in society, and to the changing nature of show business; stand-up comics began to dominate, for one thing. He sees Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, who were together for 10 years (1946-56) — right to the day — as "the last spectacularly successful classic comedy team."

Then again, later on he calls the Smothers Brothers "one of the last classic comedy teams to achieve national success."

At any rate, one thing is certain — the Smothers Brothers remain the last major team still performing.

E-mail: Roger K. Miller, a journalist for many years, is a free-lance writer and reviewer for several publications and a frequent contributor to the Deseret Morning News.