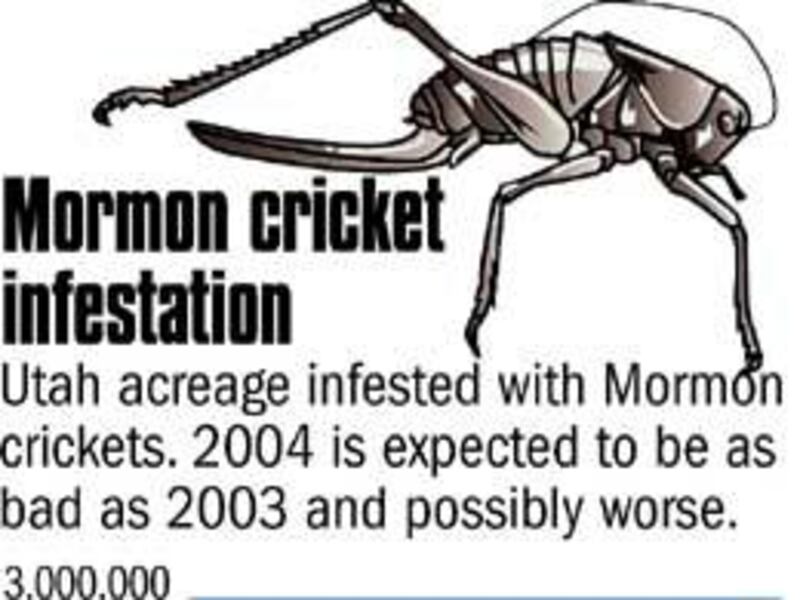

Mormon crickets attacked 2.7 million acres of western Utah rangeland, farms and desert last year, and this year's onslaught probably will be worse.

Year by year, as drought continues, crickets have generally increased in number. "We expect that to happen again, barring some weather pattern that changes," said Matt Palmer, the Utah State University extension agent who covers Tooele County.

"There's likely to be more this year than there was last year," in terms of infested acres.

Crickets already have begun to hatch from their eggs. They show up when the soil temperature reaches 40 degrees, he said.

Tooele Valley's first horde has emerged on the western side of South Willow Canyon. "Their numbers are pretty high" and the young crickets look healthy, "which is a disappointment."

"They're hatching in pretty big numbers," Palmer said.

Mormon crickets have been infamous since June 1848, when the insects began to devour the Utah pioneers' crops. Settlers fought them without success. They faced starvation as millions of bugs invaded.

Then, as recorded in diaries and recollections, came what has been known ever after as the miracle of the seagulls. A white cloud of California gulls descended and feasted on the crickets, disgorging and eating more. The crops were saved.

Today vastly more cropland is involved than 156 years ago, and gulls can do little to stop the modern infestation.

"Every cricket has an average of 86 eggs it lays, so you can see how fast populations can get out of control," said Palmer.

The Mormon cricket (scientific name Anabrus simplex Haldeman) is a large, flightless and notably unattractive bug that looks something like a grasshopper. It is actually a species of shieldback katydid.

Although the crickets don't have wings, they move together in dense waves, spreading across fields. "They creep along the ground and devour the forage," Palmer said.

"They kind of congregate and start migrating, and that's when people see them. When they start crossing the road or crossing your field, they come in these huge bands."

Palmer recalls wading into a swarm of crickets that he estimates was 50 yards long and 25 yards across. All of the creatures were moving in the same direction. The big bugs can crowd together at 100 per square yard.

For a band 50 by 25 years, that makes 125,000 insects — in just one gang. And countless swarms can be on the hop.

When they're moving, you can hear the rustle through the underbrush. It's eerie, he says.

Drivers hitting patches of crickets may find their windshields plastered with bugs, and their wheels sliding across slick patches of grease from the crushed bugs.

Worse, the crickets are ravenous, eating yard plants, gardens and alfalfa fields. "They really like alfalfa," said Palmer.

So far, Mormon crickets have been tearing up western Utah — mainly Tooele, Juab, Millard and Beaver counties. But they are on the march toward the central portion of the state.

"They're starting to flow into Utah County," entering from the vicinity of Eureka, Juab County.

The cricket population boom is related to Utah's drought, which is entering its sixth year. Dry weather increases the chance that cricket eggs will hatch.

"The spring has been very dry and great for hatching those eggs out," he said.

Palmer, fellow USU extension agents, landowners and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are teaming up to monitor the cricket attack.

They are setting out exclusionary cages, devices like buckets that are screened over. These will keep crickets off little swaths of vegetation. The scientists want to study damage to small grain, alfalfa and range forage.

"We'll compare inside the cage where the crickets are not eating, to outside where crickets are eating, to determine how much forage they're actually taking," he said.

About 12 or 15 of the cages are being set out in each of the four counties where the crickets are worst.

A few natural predators are helping. Coyotes may eat them. Sage grouse numbers are booming because of the insect cornucopia.

And what about gulls? According to Palmer, they're pitching in, too.

"You can see them still working on patches of Mormon crickets. The seagulls will come in and clear them off, but it's too small an area to really help."

Spraying is one of the few tools that shows any promise.

Several years ago, he said, a rancher in Terra, Tooele County, reported his alfalfa field was infested. Experts treated the field and saved all of one crop and part of another crop of hay, of what would normally have been three crops.

This protected $15,000 worth of hay and a lot of rangeland.

Meanwhile, specialists are tracking the bugs, trying to figure out where the next hot spots will be, Palmer said. "We figure we'll get some pretty good data spread out across those counties."

E-mail: bau@desnews.com