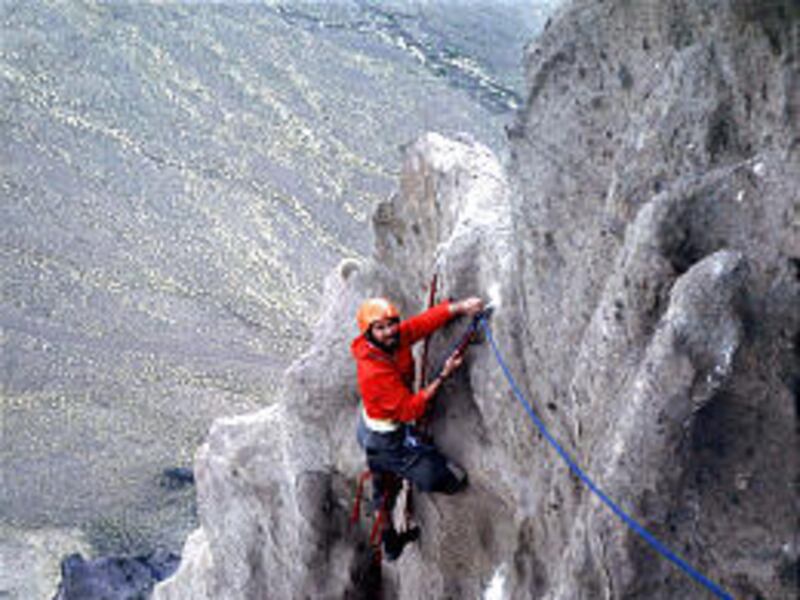

MOAB — When Eric Bjornstad danced, there was no music, only the sound of the wind and his own heavy breathing. He moved alone, followed no particular steps, but his movements were as graceful as any waltz and as meaningful as any ballet. They had to be. His life depended on it.

Bjornstad was a rock climber. No, he was a climber of tall pinnacles — towers to some. They are the freestanding rock spires built by wind and water over eons, always much taller than they are wide.

And it was, he says with a remembering smile, "This vertical dancing that I found so rewarding . . . To make a smooth, difficult move, not lunging, and not using your muscles to pull you up, but just little steps, keeping the body over your feet in perfect balance . . . It was exciting."

Bjornstad made thousands of such climbs. Many were first ascents; many were made on routes others had failed to conquer.

Now 70, and slowed by an earlier injury, he spends his time writing and, when the opportunity presents itself, sitting around a campfire with younger climbers, "telling stories and lies," he says, then smiles.

There was nothing in his early life that Bjornstad felt triggered his desire to rise above ground level, hundreds of feet, holding onto little more than a bump on a rock or hairline crack in a sheer stone wall.

Maybe it was the rope that hung in his father's garage that he frequently climbed, he says. Then again, maybe it was just something he was meant to do.

Whatever it was, climbing was his life.

He has difficulty walking now. His features look much younger than his years, but not his movements.

He suffered a back injury in a fall in 1986 that nearly cost him his life. A mental error and a bad knot caused him to fall onto a steep rock face and stop, spread-eagled on his back, only inches from a thousand-foot drop. As he lunged for a rope, his hold loosened and he began to slide over the edge.

"Luckily, I got the rope," he remembers, taking a deep breath and exhaling. "That was my only serious accident, but it damaged my sciatic nerve."

There were other close calls over the years, but none that would stop him from climbing.

Bjornstad began his adventurous life exploring caves in the 1950s while living in Berkeley, Calif. In 1959 he moved to Seattle, and found there were no caves and people did their climbing above ground.

He came to Monument Valley in the 1960s with his climbing companion, Fred Beckey, to make the first ascent of the Eagle Rock Spire, which he calls a 16-day marathon.

Ninety-eight percent of all his climbing was done with Beckey, who is also recognized as one of America's great climbers and who has probably made more first ascents than any climber in the United States or Europe.

"I fell in love with the desert and the soft rock. It's a lot more challenging," Bjornstad says. "I haven't been off the continent, but I've climbed in Alaska, Canada and Mexico, but desert climbing was by far my favorite."

He moved to Moab shortly after and over the years, no matter his official address, he has been securely tied to the area.

Early in his climbing he preferred freestanding towers and spires to walls and mountains because of their isolation

"I liked the lonesomeness of it," he says. "It's so quiet, so beautiful. And I find the rock is very sculptural."

And, he was quick to point out, the desert, in many places, is still a frontier. While many of the preferred areas around the country have been "climbed out," there are thousands of routes yet to be discovered in and around the deserts of Moab.

Near the entrance to the Needles District of Canyonlands National Park, for example, on the vertically fractured walls, there are more than 2,000 recognized routes, "and probably 2,000 more yet to be identified."

Bjornstad, himself, preferred areas that hadn't been climbed. What he looked for was a route that was aesthetically pleasing . . . a crack that went from top to bottom in a straight line and didn't wander. And, always, he looked for rock "he could work with . . . nothing that could crumble or fall.

"I wanted to climb as cleanly as possible," he says, waving his hand in a vertical line.

Many of Bjornstad's climbs over the years were "first ascents." Meaning, of course, he was the first to successfully select a route and summit. Others would inevitably follow. Many more of his climbs were listed as being among the first. He and Beckey, for example, made the seventh ascent of Liberty Ridge on Mt. Rainier in Washington. Today, it is a well-climbed route.

Bjornstad was the first to climb Moses, a popular tower, 600 feet high, near Moab. Today there are five routes on the narrow pinnacle of rock and it, too, is often climbed.

He spent two days climbing and fixing ropes for the first ascent of The Bride, a tower in Canyonlands. He then climbed down, called his friend, Beckey, and on the third day they were able to summit.

He was the first to climb the El Matador route up Devil's Tower in Wyoming and the 574th climber to summit the mountain. Today, the standing rock mountain is climbed between 2,000 and 3,000 times a year.

The two men made the second ascent of west peak of Moose's Tooth in Alaska, "And most every climber these days knows Moose's Tooth," Bjornstad says.

He was the first to climb Echo Tower in the landmark Fisher Towers east of Moab. It is only 550 feet high, but it took five days and two bivouacs to summit.

"It was in late October, and it was cold," he says. "We hung on ropes the last two days. You get so tired in cases like that, that at night you sleep standing up."

Not all his climbing attempts were successful. On one particular climb on Shiprock, an 1,800-foot tower in New Mexico, while climbing with Beckey, they ran into bad weather, had water bottles freeze and break and a tent pole break, among other things. After 20 days he left. Beckey stayed and would eventually summit.

In 1970, he was asked to supply technical help in the movie "Eiger Sanction," with Clint Eastwood and George Kennedy. He took the job, not to be in movies, but because it gave him the chance to legally climb the Totem Pole in Monument Valley.

"No one was legally allowed to climb the Totem Pole, which was 'Big Ben Tower' in the movie. It is the tallest, thinnest tower in the world. It's 400-feet high and only 18 feet thick," he says.

"I got in the movie by accident. The stuntman couldn't climb fast enough, so they asked me to try. The first time I wasn't fast enough, so I asked if I could try again. I took off all the safety gear, dressed in George Kenney's shirt and hat and went for it. I think I was in the movie for all of five seconds."

It was during that filming he had one of his "close calls." While retrieving ropes from the top of the tower, he noticed, as he neared the top, the wind had moved the rope over sharp rock and left it cut and frayed.

"I could either climb the final 10 feet and hope the rope held, or climb down. I figured my best chance was to climb up. I made it, but boy was the adrenaline pumping," he says, leaning back on the couch in his small trailer.

He admits, in a more serious mood, that climbing is much safer today, mainly a result of new, high-tech equipment.

He stops, points to the far wall that holds his antique collection of climbing equipment and notes that "many climbers have never seen equipment like that and likely never will."

In the early days, he says in a solemn voice, he would lose "about four climbing friends a year. That doesn't happen these days. Ropes used to break and welds on pitons broke all the time.

"You can hang an 18-wheeler from one of the new ropes today and it won't break. But I like the idea of safety. There's just so much more equipment in place for protection. It's fail-proof now. It's just one of the reasons climbing has become so popular. That and all the media coverage it gets.

"Also, climbers today are in much better shape. To stay in shape we used to run and chop wood. It's the way most of my climbing friends trained. It served two purposes for me — I exercised and I stocked up on firewood."

He says he continues to stay in touch with climbers. A logbook stashed away in a little nook carries the names and comments of some of the world's best-known climbers.

"People glance through it and can't believe all the famous people who've stopped here," he says. "But they've all come . . . and I have them sign the book. It's a way I stay in touch with climbing."

During his lifetime, Bjornstad has held a number of jobs in order to support his climbing, including that of a draftsman, piano salesman, gardener, bartender, truck driver, tree topper, handyman and coffee house owner.

His passions include writing poetry, chess, speed typing and classical music. He plays both the piano and oboe.

Today he lives in a small trailer on the outskirts of Moab, which comes with adjoining living room and kitchen, and a bedroom. There's enough room in the living area for a swivel chair and table, where he does his writing and makes etched; recycled glass ornaments that he sells; a small TV; and stacks of papers and files. On the far wall there is a large bookcase filled with books. "I read voraciously," he says.

His first climbing book, "Desert Rock," is out of print. He has been commissioned, however, to expand it into seven new volumes. Four are currently available. The fifth, he says, is nine-tenths finished.

"I'm also working on a biography. I've completed seven of 17 chapters. It's another way I vicariously stay in touch with climbing," says Bjornstad, who admits he dropped out of high school in the 10th grade, ran away from home and calls his educational background "self-taught."

"I'm also working on a book about the history of climbing in the desert. It will be profiles on well-known desert climbers and stories of how climbs got their names. How some routes got their names is very interesting. A couple of climbers, for example, were looking for a name, walked into City Market here in Moab and the first thing they heard was, 'Wet cleanup in aisle No. 9.' That became the name."

Bjornstad continues to take tours around the Moab area — "To talk about the flora and fauna and more about climbing that people would probably care to hear" — and work on his books.

It keeps him busy, he says. And, in some way, keeps him in touch with the desert . . . and his thoughts, at least, on climbing.

E-mail: grass@desnews.com