POMPEII, Italy — It was just after 1 p.m. on a cold, wet day. Four bedraggled, scholarly looking men stood under their umbrellas at the entryway to the ruins of Pompeii. Rain spattered the stones at their feet.

They wore plastic tags identifying them as official guides. When I said I needed one, they eyed each other uncomfortably. I think they were all ready to go home; it wasn't a good day to be working outside.

After a moment's hesitation, Mario Improta stepped forward to introduce himself. He wore a lumpy tweed cap, a weathered wool jacket and a silk ascot. His beard was a wild sprawl of black and gray hair, and more curls tumbled out from under the cap. I was happy that he'd agreed to stick around.

I was passing through, traveling by train from Sorrento to Rome, and had only a day to spare. I'd always wanted to see this place; it's a snapshot in time, an entire city destroyed and at the same time preserved by one disaster.

We began walking up a narrow road of giant smooth stones. "Everything you see from now on is original — 2,000 years old," he said.

The ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum, another coastal town, were discovered in 1709 by a well-digger who accidentally struck a theater stage instead of water. Despite the damage and wear of time, I was astounded. I was walking down city streets, arranged in square blocks, made up of one-story buildings that stood shoulder to shoulder.

We stopped at the Forum first, an open space surrounded by temples and government buildings at the heart of Pompeii. We stood in front of the Temple of Apollo, where a blackened bronze statue of the god resides on a marble pedestal. Naked save for a sash draped over his arms, his empty hands are frozen in a pantomime of archery, preparing to shoot an imaginary arrow with a missing bow.

"Pompeii was an important regional center," Improta said. "Twenty thousand people lived here. It did not have famous generals or emperors, but regular people. And that, ultimately, is what makes Pompeii important. It shows the life of regular people in Roman times."

The clouds had cleared enough that Improta could point out the looming form of Vesuvius — the massive volcanic mountain — to the north.

"They called it Vesuvo in the Italic language before the Romans came. It means 'Mountain of Fire,' " Improta said.

"It was a summer day, Aug. 24, when the eruption started. . . . In a day, 6 meters of pumice and ash covered the town. But it wasn't the ash that killed the people, but poison gas given off by the stone. Archaeologists guess this because of the position the people were in when they died — with their hands held to their faces and their faces contorted as if trying to get air, consistent with death by asphyxiation."

The ash hardened around the buried citizens of Pompeii. The people eventually decomposed and evaporated to dust, leaving perfect casts that reveal their clothing, musculature and even expressions.

The weight of ash and stone caved in some roofs and walls, but for the most part, it preserved the city as it stood that day in A.D. 79. The murals on the walls of homes, the graffiti on street corners, the lead-and-terra cotta piping of the town's water system — they're all here.

From the Forum, Improta led me on a street tour of the densely built city. The size and shape of doorways gave no indication of what was behind them.

Improta took me into one of them. "Here is a typical house of a rich family. In the front, we have an atrium with rooms around it. The atrium brought in light. Rain was collected through drains in the marble floor. In the next chamber, a walled garden." Red paint still clung to the walls.

We stepped back onto the street and peered into the next door, which looked quite similar. But it opened onto a dingy cube not even 8 feet square. "This was probably a shop selling street food. Maybe roasted peanuts, snacks, wine. The shopkeeper lived upstairs," Improta said.

Romans loved to drink and fornicate, and there was plenty of evidence of both in Pompeii.

Improta showed me a typical bar. In it was a countertop with sauce-pan-size holes cut into the surface. Underneath were jars, insulated by concrete to keep the wine hot or cold, depending on the season. The exterior of the counter was a fabulous abstract mural of broken pieces of marble, pressed into the cement. "It's beautiful," I said.

"We're now entering what you might call the red-light district," Improta said, "but here Pompeians marked it with a phallic symbol."

Until turning onto this street, we'd seen perhaps a dozen other people in the ruins; here, 20 were trying to crowd through the door of the town's largest and best-known brothel.

"Still popular," I said.

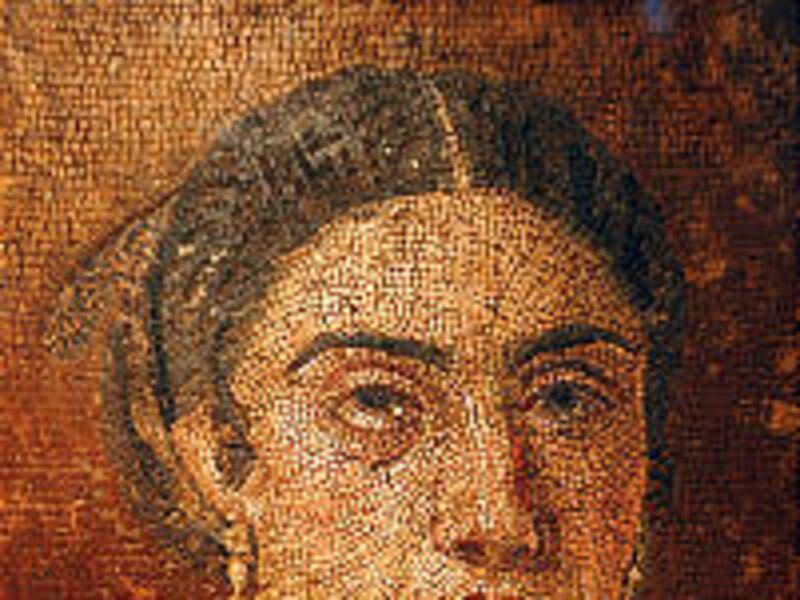

We walked into one of Pompeii's bath houses, its large concrete dome undamaged by the volcano. Even on that dreary day, the opening at the top filled the space with gentle light. Improta showed me a bakery, a "small" theater that could seat 1,000 people (the big one could seat 5,000), and some of the most famous homes — such as the House of the Tragic Poet (named for the murals found inside). The tile mural in the doorway depicts a growling dog straining at his leash and the words "Cave Canem" — Beware of Dog.

Improta told me that there were only a couple of written accounts of the explosion of Vesuvius. He recommended that I look up the letters of Pliny the Younger if I was curious to hear a survivor's story.

I made a point of taking his advice, and reading those words now brings a somber poignancy to my memory of that day in Pompeii.

Pliny the Younger watched the blast from the nearby town of Misenum and managed to escape with his life. He wrote that the cloud of ash created total darkness, "as if the light had been put out in a closed room."

"You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men. . . . Many besought the aid of gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore."

Distributed by Scripps Howard News Service