Twenty years ago today, one of the most bizarre chapters in Utah history began when a nondescript man wearing a high school letterman's jacket and carrying a package went into the Judge Building and took the elevator to the sixth floor.

The two murders Mark Hofmann committed that bright October day were cold-blooded, clumsy attempts to divert attention from his life's work — hundreds of forgeries and lies that tampered with LDS and American history. For years, it turned out, Hofmann had been producing phony signatures and documents and photos and coins, successfully convincing handwriting experts and forgery detection machines that all of it was authentic.

The reach of his forgeries — from Emily Dickinson to Mark Twain, George Washington to Joseph Smith — and the cunning with which he tricked a nation's document collectors continue to intrigue authors and investigators. So far, seven books have been written about him. This weekend, yet another symposium is being held to analyze his crimes, as forensic document examiners from 33 states gather in Salt Lake City to talk about the arcane details of ink and paper.

Meanwhile, Hofmann's forgeries and counterfeiting are still leaving their mark. His doctored documents continue to surface and are sometimes sold as originals even when there is proof that they're "Hofmanns." Two years ago, a penny Hofmann claims he altered sold for $48,300 at a Beverly Hills auction.

Hofmann himself sits in a 7-by-10-foot cell in the Utah State Prison, a prisoner for life, sharing those 70 square feet with convicted murderer and religious zealot Dan Lafferty. Hofmann has never granted an interview to the media and has never fully explained the murders and his motives. He does occasionally write letters to his family. As always, he prints; these days his printing has a slightly backward slant.

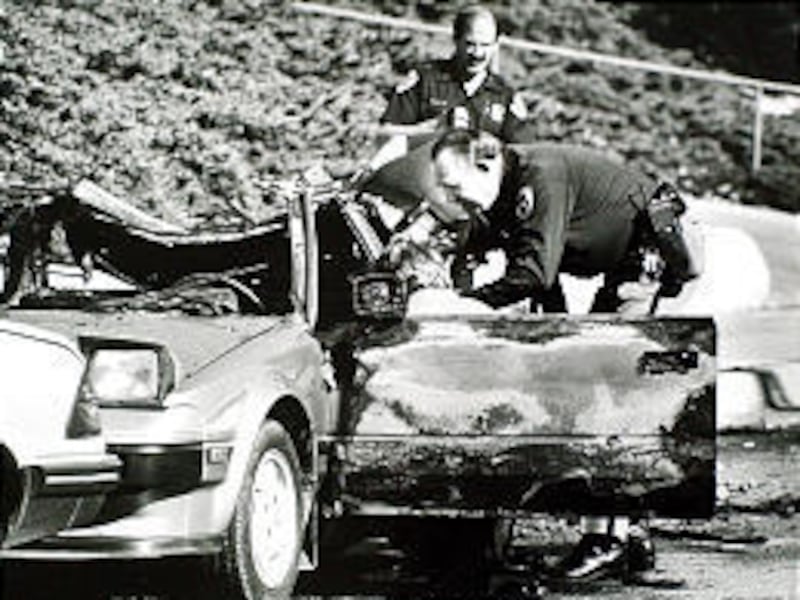

The first bomb exploded a few minutes after 8 a.m. on Oct. 15, 1985, killing Steve Christensen when he reached down to pick up a package in front of his office in the Judge Building. The second bomb exploded about 90 minutes later, killing Holladay housewife Kathy Sheets when she picked up a package in front of her home.

At first it seemed that someone was targeting employees of the beleaguered CFS Financial Corp., because Sheets' husband, Gary, was CFS's president, and Christensen was formerly one of the company's vice presidents. But when a third bomb exploded the next day, suddenly the motive seemed less clear.

The third victim, injured but still alive, was Mark Hofmann, a man unknown to most Salt Lakers but a minor celebrity among LDS historians and collectors.

By then he had already appeared in Time magazine as the young document dealer who had discovered a long-lost document of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Anthon Transcript, on which LDS Church founder Joseph Smith had copied Egyptian characters from the gold plates that were later translated into the Book of Mormon. Three years later, Time had written about a more bizarre Hofmann find — a letter written by Smith's close friend Martin Harris. The letter recounted how the church prophet had encountered a white salamander — that transformed itself into a spirit — guarding the gold plates. This second letter, known informally as "the Salamander Letter," had called into question the origins of the church, because no mention of anything that fantastical had ever appeared in church writings.

Immediately after the third bombing, Hofmann became a suspect in the Oct. 15 pipe bomb murders. But the case was so complicated the district attorney's office, for the first time ever, had to use a computer to keep track of the information. Investigators also began constructing a timeline, posting pieces of information on the blank walls of a "war room." At first they couldn't figure out how the stuff on one wall related to stuff on another wall, remembers prosecutor Bob Stott. Eventually, though, they zeroed in on the apparent motive: a tangled web of lies and debts, forgeries and frauds, that had made Hofmann feel backed into a corner, stalling for time.

Steve Christensen was a target because of his involvement with several of the document transactions. An amateur historian, Christensen had bought the controversial Salamander Letter from Hofmann for $40,000 and had donated it to the church in 1983. What apparently got him in trouble with Hofmann, however, were some 1985 transactions, including the "McLellin collection" that Hofmann said contained damning information about the church's early history.

Hofmann peddled the McLellin collection — sight unseen because, in fact, it didn't exist — to several potential investors. With Steve Christensen's help, he convinced the late LDS general authority Hugh Pinnock to help secure a non-collateral loan for $185,000 from First Interstate Bank so that Hofmann could buy the collection and donate it to the church to keep it from falling into "enemy hands." He negotiated a separate $154,000 deal with Salt Lake coin collector Alvin Rust for the same collection.

At that point, Hofmann was receiving pressure from all fronts to repay the loan and to either give back the investments or come up with the documents. Meanwhile, the deal Hofmann had been hoping would help him repay these and other bigger debts wasn't panning out. For a while, it had looked like the Library of Congress was going to buy Hofmann's rarest "find" yet — the early 17th century "Oath of a Freeman" — for $1.5 million. But in June the deal went sour.

Hofmann's deals were one big Ponzi scheme, says former Salt Lake City police detective Ken Farnsworth. Hofmann would promise investors a 30 percent or 50 percent or 100 percent return on their investments in rare documents, would take their money to repay earlier investors, then would look for still newer investors to pay off the others. At the same time, Hofmann was getting loans from local businessmen using real, rare books from his personal collection as collateral. And his checks were bouncing all over town.

Farnsworth, who investigated the Christensen and Sheets homicides, remembers that investigators kept a running tally of Hofmann's debts as the case became clearer in the winter of 1986. "We made this thermometer, much like one of those charity benefit thermometers" that show a steadily rising "mercury" of dollars, Farnsworth recalls.

The total of debts — $415,000 to Salt Laker Thomas Wilding and others in his investment group; $185,000 to the bank; $20,000 to a dealer in California for a Sherlock Holmes manuscript; a $180,000 down payment on a new house on Cottonwood Lane, and on and on — eventually reached $1.1 million, Farnsworth says.

"When you put together this whole morass of bad deals he had going on, he was in a box he couldn't get out of," he said. "It would have taken a whole year of forgery to get out of it."

In addition, Hofmann knew that Massachusetts autograph expert Kenneth Rendell was planning a trip to Salt Lake City in late October. Hofmann knew that Rendell would be visiting Christensen, who was thinking of buying a piece of Egyptian papyrus Hofmann said was from the McLellin collection — but which, in fact, Hofmann had bought from Rendell earlier in the summer.

However, according to George Throckmorton, the Salt Lake City forensic examiner who helped pin down the Hofmann forgeries, Hofmann's real motivation for the Christensen murder was not the McLellin collection nor Rendell but a separate transaction.

"I'll tell you, it has something to do with an old farmer in Idaho," he said cryptically, perhaps referring to Sidney Jensen, investor Thomas Wilding's brother-in-law.

Throckmorton, head of the Salt Lake City Police Department's crime lab, is spearheading this weekend's "The Hands of Hofmann, Motive for Murder" symposium. He has also just finished writing a book that will detail his findings.

"Killing Christensen might have bought him some time" — if Hofmann himself hadn't immediately become a suspect, says former detective Farnsworth. The murder of Kathy Sheets was a diversion but was, in a sense, random. As Hofmann later told his parole board: "At the time I made that bomb my thoughts were that it didn't matter if it was Mr. Sheets, a child, a dog."

Steve Christensen and Kathy Sheets were Hofmann's most tragic victims. But Hofmann also had three other financial victims: the LDS Church, which owns 446 Hofmann forgeries and whose history was challenged by some of Hofmann's more damaging distortions; coin and document dealer Al Rust; and Provo document collector Brent Ashworth.

Ashworth, who says he lost his retirement — about $400,000 — to Hofmann, is a self-deprecating attorney with a passion for old papers. He has walls and file cabinets full of Mormon and Americana documents. He used to have a much bigger collection — an original copy of the 13th Amendment, a handwritten letter written by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War — but he traded these and more to Hofmann for early LDS documents that turned out to be bogus.

During their four-year business relationship, Ashworth was continually amazed that Hofmann was able to find the very documents Ashworth wanted the most, including a letter written by Joseph Smith's mother, Lucy Mack Smith, and a letter written by Joseph Smith from the Carthage jail.

"I don't understand," a reporter began as she interviewed Ashworth, to which he interrupted, "How stupid we were?"

"Collecting is an insanity," he said, by way of explanation. "My wife calls it a greed. It might be a greed. I've tried to analyze it myself, but I'm not very good at that.

"I don't remember ever being suspicious but one time," Ashworth said. One day, Ashworth recollects, he went to Hofmann's home and ran into the dealer exiting his house with a document Ashworth recognized as a Paul Revere. "Doggone it if the ink didn't look not quite dry," he remembered. The sunlight, he says, seemed to reflect off the surface of the ink. "It almost looked brand new."

But Ashworth just brushed the observation aside, he says, only remembering the image later, when it was too late. Eventually, he did begin to think of Hofmann as a liar and con man, who bounced checks and made promises he didn't keep. But even when Ashworth occasionally thought the documents Hofmann showed him didn't look real — including the Salamander Letter — he never thought Hofmann himself was the forger.

As Curt Bench, former friend and former head of Deseret Book's rare book department, said: "Nobody ever thought Mark could have been the one, because we trusted him." And, too, "there were no known (LDS document) forgeries in our field, so it wasn't on our radar."

Whenever someone did question any of his documents, Hofmann always blamed the person from whom he had bought them. Several times, when New York handwriting expert Charles Hamilton told him some signature or other looked like a fake, Hofmann would quiz him as to exactly why — then went back to his basement and tried harder to get the signature right, Ashworth says.

Some people think Ashworth was the intended victim of the third bomb. Hofmann contends he was trying to kill himself. Prosecutor Stott thinks Hofmann was just trying to damage his car so he could claim that the McLellin collection had been destroyed. The truth sits with Hofmann, who, say his friends and enemies, can't be trusted to ever tell the truth about anything.

"If I can produce something so correctly, so perfect that the experts declare it genuine, then for all practical purposes it is genuine," Hofmann once told his former prison guard, Charles Larson, author of "Numismatic Forgery." In Hofmann's mind, if it was a perfect forgery, no one was being deceived.

"He has little or no conscience," his former friend, Shannon Flynn, said. "He doesn't think about things in moral terms, like punishment by God. . . . He believes in a sense we just live in a biological system," where a murder is the equivalent of a lion killing a water buffalo, simply for survival, Flynn says. "He killed those people to survive, to get out of it. Things were closing in on him. His forgeries were very close to being found out."

"This is what makes Mark Hofmann so stinking dangerous," Flynn added. "You and I would have just gotten caught for forgery, and gone to prison for three years. But Hofmann has no limit. Would he kill again? If the pressure was high enough, you'd better believe it."

He murdered to save himself. He forged to make money and, apparently, to hurt the LDS Church.

"A Burning Testimony," a poem he wrote in prison seems to sum up his feelings: "In my opinion (And I 'know' I'm right!)/The Book of Mormon can best shed its light/ at four-fifty-one degrees Fahrenheit."

Ashworth believes Hofmann's anger resulted from the fact that Hofmann's grandfather had been excommunicated for practicing polygamy. Ashworth now owns Hofmann's Bible from his LDS mission days in England, and reports that "almost all the notes (in the Bible) were about polygamy. It seemed to be on his mind all the time."

And, too, Hofmann forged simply because he liked tricking people. He liked getting away with whatever he could.

"Looking back now, it seems obvious," said Salt Lake City coin dealer Bob Campbell — that one man couldn't have found so many rare documents, that the photos he passed off as old were on paper that was too thick, that the coins he sold weren't authentic. "But they so much wanted to believe," Campbell said. "So many people."

Not long ago, Salt Lake City book dealer Ken Sanders, owner of Ken Sanders Rare Books, almost bought a hand-written Brigham Young calling card. He placed a bid on it — for $1,200 — and then realized he had seen an item just like it a couple of years earlier when his store hosted a Mark Hofmann symposium called "Authentic Fakes." Later, he found out that the owner of the card had had dealings with Hofmann in the 1980s.

Sanders tells this story on himself to point out how, even though Hofmann has been locked up for more than 18 years, some of his forgeries are still in circulation, and people continue to be fooled. "Sometimes they're sold innocently, sometimes not so innocently," said Sanders, who serves on the security committee of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America.

"You couldn't sell a Mormon document for a decade after Hofmann" pleaded guilty, Sanders says. Even now, any document Hofmann may have touched, or whose pedigree can't be traced back to before Hofmann, is suspect, he says.

But the Americana documents are another matter. Just how many Hofmanns are still being traded isn't known. A sheet of paper found under Hofmann's jail cell mattress in 1988 listed 129 documents and signatures he hadn't mentioned during 1987 plea-bargained interviews with prosecutors. But since honesty wasn't Hofmann's strong suit, no one knows if the list is accurate.

Jennifer Larson, a Rochester, N.Y., book dealer who has researched Hofmann documents, says, "I know fairly surely of several dozen" Hofmann forgeries still in circulation. The lessons learned from 1986 have been lost on document dealers, collectors, librarians and scholars, she says. "Not many people are interested in the non-Mormon forgeries that may be unidentified and unlocated," she said. "And even fewer are interested in the wider problems of authentication that Hofmann's success should have exposed.

"If anything," she said, "I think the problem is now worse than it was in the 1980s. . . . The Internet now offers an easy, efficient, anonymous method of offering questionable merchandise to a very wide audience; while many buyers might be suspicious, all a forger or a thief has to find is one."

Both forensic expert Throckmorton and collector Ashworth say they have run across rare document dealers who have sold items that have been pointed out as Hofmann forgeries. Throckmorton remembers a Daniel Boone letter sold by a Denver auction house; he told the dealer the letter was forged, but the response, says Throckmorton, was "We don't care." The dealer explained, "We never guarantee it's authentic. We just guarantee we'll give them their money back if they're not satisfied."

Throckmorton says he knows of one man who had bought many Hofmann documents, planning to sell them to fund his retirement. He knows now they're fakes but continues to sell them on eBay, Throckmorton says.

Ashworth remembers seeing a Hofmann Paul Revere letter at a Las Vegas auction house in 1997. He warned the dealer, who said it had been "checked out by our experts." It sold for $31,000. Then there was the famous Emily Dickinson poem — not only forged by Hofmann but written by Hofmann as well. Ashworth told Sotheby's auction house it was a fake, but the dealer still sold it to a Massachusetts museum, which later discovered that Ashworth was right.

Was he the best forger — or at least the best forger who was caught — in the past 1,200 years?

That's what the Southwestern Association of Forensic Document Examiners voted a few years ago. They have a grudging respect not only for the skill of Hofmann's handwriting — no stops and starts, no tell-tale angles — but by the breadth of his work.

While most forgers specialize in, say, Abraham Lincoln, Hofmann could do 86 signatures. He made his own ink, created his coins and currency, fashioned his own postmarks.

"He had his documents authenticated by the best: the Library of Congress, the American Antiquarian Society, the FBI, the University of California, the McCrone Research Institute," said Throckmorton, who prides himself on being the examiner, along with Bill Flynn of Arizona, who uncovered Hofmann's secrets.

Book dealer Jennifer Larson, though, doesn't give Hofmann such high marks. Lots of other forgers are better at ink, paper, calligraphy, history, aesthetics, she says. What Hofmann excelled at though was "an ability to select and exploit his victims with a heartless eye towards their particular weaknesses, and a total indifference to the damage that he was doing to them, and to trust among human beings in general," she said. "I think this is a psychiatric characteristic that he can't help and merits no accolade."

In the end, of course, Hofmann did get caught — because of the murders, but also because of his mistakes. What the examiners noticed first, after putting his documents under ultraviolet light, was a "blue hazing effect" and ink that ran in one direction. Under the microscope they noticed that the ink was cracked. But to prove forgery they had to be able to duplicate these subtle mistakes.

The blue haze, it turned out, came from blue household ammonia; ammonia increases oxygen levels, and oxygen speeds up the aging process. Hofmann would also age his papers by putting them in a fish tank, along with a little toy train transformer. When he turned on the transformer it would create ozone. And "ffffft," Shannon Flynn said, "that thing just aged 100 years in 10 minutes." Hofmann also aged his documents by ironing them and letting weevils munch on them.

The hardest mystery to crack was the ink. Finally, after consulting with Ph.D. chemists and trying formula after formula, Throckmorton was at a toy store one day buying a present. And there, in the science aisle, was a chemistry set. "Green copperas," said the front of the box — one of the inks listed in an old book police had taken from Hofmann's basement. The discovery helped solve the case.

Like the murders themselves, Hofmann's forgeries were what Linda Sillitoe and Allen Roberts, authors of "Salamander: The Story of the Mormon Forgery Murders," call "a delicate balance of care and risk."

A Betsy Ross letter now owned by Al Rust is one of Hofmann's sloppier efforts — he found a letter from another Betsy, added the "Ross" and changed the date. The problem was that the oft-married Betsy wasn't a Ross in 1812.

"He told the police that if his wife needed $20 worth of groceries he'd do a $20 forgery," Ashworth said. "It's ridiculous he took that kind of risk. But I can see why. At the end we were buying whole collections that didn't exist."

At one point he even created some forgeries by ordering negatives at a printing company next door to one of his document dealers. "I think as the years went by," Sanders said, "his arrogance went through the roof, his sense of omnipotence, that he could fool anyone, anytime."

Kathy Sheets' family hopes that this 20th anniversary of the bombings will be the end of the protracted attention on Mark Hofmann, this near-glorifying of a man who murdered two people.

"I think they've kind of idolized him and given him a unique status I don't think he deserves," said Kathy Sheets' daughter Gretchen Sheets McNees, now a detective with the Salt Lake City Police Department. "Yes, he did these forgeries, but he also killed two people and didn't care who he killed."

The interest in Hofmann continues, though. Sometimes his forgeries bring extra money just because they were forged by Hofmann, says Throckmorton, who points to a first-edition Book of Mormon signed by Joseph Smith. The book was worth $200,000 with the signature, $150,000 without the signature — and $175,000 if the signature proved to be a Hofmann.

Hofmann, meanwhile, spends 22 hours a day in his prison cell, Board of Corrections spokesman Jack Ford says. There is a bunk bed but no chairs. He and his cellmate, Lafferty, share a TV and headphones. A controversial plea bargain kept Hofmann from the firing squad. He was sentenced to five-years-to-life — but the next year, after a lengthy interview, the Utah Board of Pardons told him he'll never get out of prison.

Occasionally, Hofmann apparently sits on his bed and writes poetry, which he mails to family members.

Rare book dealer Ken Sanders has a copy of one poem, which he keeps in the store's safe along with several other pieces of Hofmann memorabilia. The poem is called "Hallelujah!"

Think I, each hour as the cop walks by:

There, but for the grace of God, go I.

E-mail: jarvik@desnews.com