Janet Mortenson doesn't sugarcoat it — she hates Wal-Mart.

She hates the crowded aisles, long checkout lines and stacks of merchandise at "everyday low prices."

But most of all she hates the retailer for putting her wholesale shop out of business. One by one, Rainbow Crafts' loyal customer base was sucked away as clients' rural stores closed in the shadow of Utah's retail giant: Wal-Mart.

"When a Wal-Mart goes into a small town, it affects so many people," said Mortenson, whose Salt Lake store served clients throughout the state. "The chains just seem to be getting bigger and bigger, and the independents are folding right and left."

Some see it as David vs. Goliath. Others use stronger language, pegging it as good vs. evil.

But no matter how defined, it is a battle waged in cities across Utah and across the nation: the battle of the big box.

At the core of the conundrum stands Wal-Mart with its concrete walls and sprawling parking lots. The store's reputation for crushing local shops has many Utah residents up in arms when the retail tycoon comes knocking.

But soon after, fears seem to fade. In areas where residents once rallied en masse against a new Wal-Mart, shoppers jockey for parking spaces.

Despite recent opposition by residents in Sandy, Riverton, Ogden and Centerville, Wal-Marts continue to pop up around Utah, with nine added in 2004 and at least four more set to be built soon. Low prices and convenience win over the store's staunchest opposition, said James Wood, director of the University of Utah Bureau of Economic Research.

"Even though you might be supporting exploitation in China and rotten wages, people still are moved by their own pocketbook. They know that going in," he said.

Wood is now studying that Wal-Mart paradox, trying to determine how a city changes in the wake of the big-box store.

It's a study that prompts the question: Will Wal-Mart bring traffic and blight to cities, or can the store breathe new life into struggling economies?

Paying the price

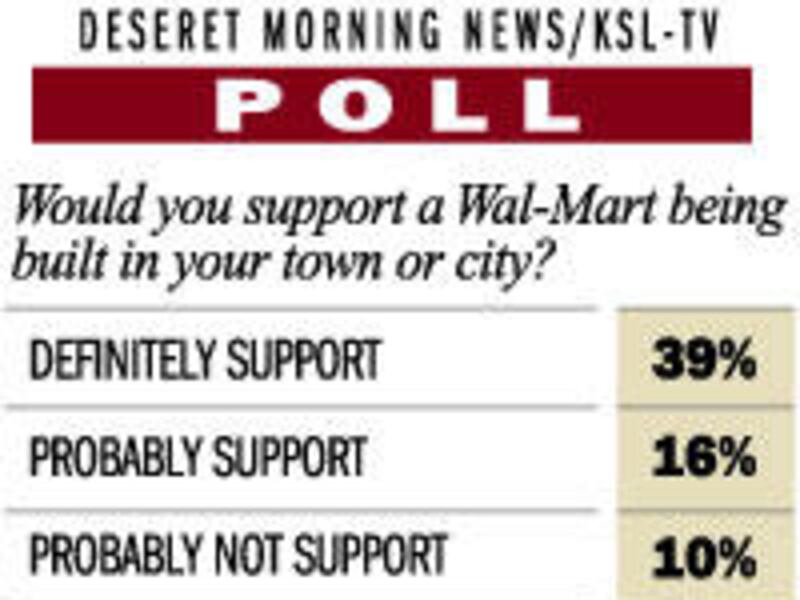

A Deseret Morning News/KSL-TV poll found 55 percent of Utahns would welcome a Wal-Mart in their city or town, even though 87 percent of respondents also said big-box retailers hurt local business. The poll, conducted Nov. 29-30, surveyed 313 residents and has a 6.5 percent margin of error.

Eric Berger, Wal-Mart regional spokesman, said the retailer has generally been well-received in Utah despite concerns about traffic and noise.

"Once our stores open and people realize the positive benefits that we make, we feel that the opposition tends to dissipate," he said.

But for Mortenson, Wal-Mart left little more than heartache. After accumulating nearly 1,500 craft-distribution accounts over 27 years, Mortenson had about 50 clients when she closed the store last April.

"I can't tell you how many people, how many accounts we lost because of stores like Wal-Mart," she said. "People will just go into the chain stores —— which I guess is just the wave of the future."

That's a terrifying notion for Kinde Nebeker, who believes local businesses are the lifeblood of a community and distinguish one city from another.

"It's a quality-of-life issue, and the thought of losing that is very frightening to a lot of people," she said. "If there are no local places we can go to, it paints a very frightening, stark, bleak picture in terms of the heart."

It's a picture that Nebeker and hundreds of other business owners in Salt Lake City are fighting as part of the Vest Pocket Business Coalition, a group that teaches local businesses how to survive in a big-box economy.

Anne Holman, a manager at the King's English bookstore in Salt Lake, said the shop has thrived for 27 years despite the encroachment of big retailers.

The key: a loyal customer base and quality.

"You get what you pay for," Holman said. "I think the only reason Wal-Mart is cheaper is because they're cheaper items. Everyone wants cheaper, cheaper, cheaper. It's just a whole downward spiral of the economy."

In Tooele, where Wal-Mart built its first Utah store in 1990, economic development director Brian Berndt said the store has shifted the dynamic of the local economy but has not driven out businesses.

Wal-Mart representatives met with local business owners in Tooele before building a store to let them know what goods Wal-Mart did not provide. For example, Wal-Mart does not sell Levi's, so local stores were able to adjust inventory to maintain a niche in the local economy.

"I think it changed the dynamic in how people do business to a degree, but I don't think it's a retail killer like it has been called," Berndt said.

Good for city coffers

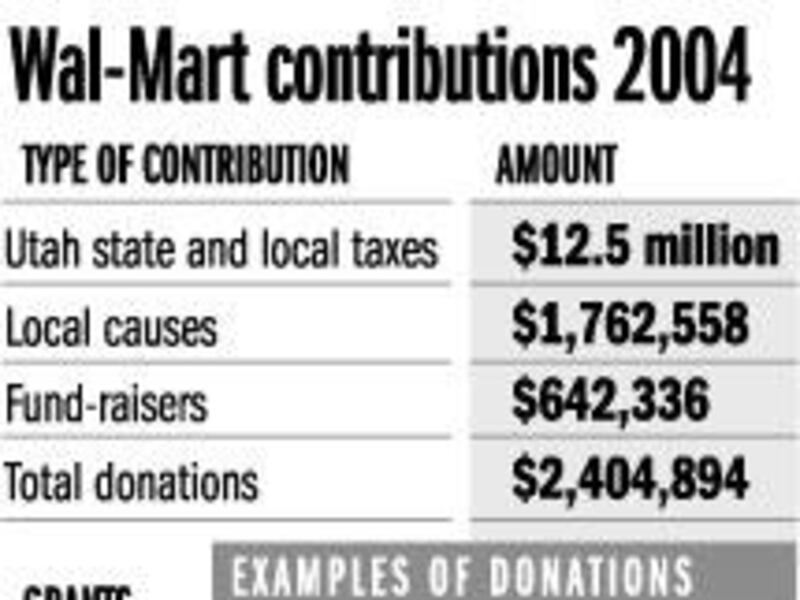

While Wal-Mart may be edging out some local shops, it is also filling city coffers. Berger said the retailer pumped more than $12.5 million in state and local sales tax into Utah last year. The company employs 14,400 people and donated $2.4 million to local causes last year.

Wal-Mart also spent about $676 million for merchandise and services with 750 suppliers in Utah last year.

"Many communities have found that we've been a positive partner in the American town," Berger said.

Eighty-one percent of respondents in the Deseret Morning News/KSL-TV poll said generating new jobs is an important consideration for public officials when deciding whether to allow a big-box retailer in the community.

Another 80 percent cited tax revenues as an important factor in whether to welcome big-boxes.

Clinton, a city of 20,000 at the northern edge of Davis County, has thrived since Wal-Mart moved in last year, said city planner Lynn Vinzant. Instead of businesses shutting their doors, the retailer has brought in more shops hoping to ride the Supercenter's coattails.

The story is the same in Sandy, where a Wal-Mart on State Street became a seed for retail growth. Nick Duerksen, planning and zoning spokesman for Sandy, said the store even boosted revenues at nearby South Towne Mall.

But the drive for sales-tax dollars often pits Wal-Mart foes against city leaders. In Sandy, residents opposed to a proposed Supercenter say city officials sold out for retail revenue.

Sandy Councilman Scott Cowdell is quick to admit his vote to allow the Wal-Mart project was based on sales-tax dollars. An economic study commissioned by the city earlier this year revealed the development could bring more than $10 million in sales-tax revenues over the next 15 years.

"My reasoning has always been — and people hate me to say this — but we need the tax revenue that it generates into our city," Cowdell said.

Mike Jerman, vice president of the Utah Taxpayers Association, said Wal-Mart and city officials shouldn't be held entirely responsible in the race for sales-tax revenues. Rather, the tax system itself is to blame, he said.

In Utah, half of sales-tax revenues go to the city where the sale was made and the other half goes to a general pot distributed by population. The point-of-sale portion, Jerman said, encourages cities to recruit big-box retailers.

"It's kind of a Cold War mentality. Basically what you have is cities competing against each other for sales-tax dollars," Jerman said.

But in Sandy, the Save Our Communities group has placed blame for the contested Wal-Mart squarely on the City Council. Cowdell and three other council members are under fire from residents who say leaders will pay for their decision in next year's election.

Working with Wal-Mart

In Draper, many residents expressed similar outrage when the City Council approved a Wal-Mart Neighborhood Market two years ago. Residents like Melanie Zitting feared the grocery store would drive out local retailers and create noise and light problems.

But more than a year later, Zitting said her complaints vanished when she learned how to compromise with the retailer.

"Until it all unfolded we didn't realize how accommodating the developers had been," Zitting said. "We don't feel intruded on."

Two of Zitting's major concerns were mitigated by talking with Wal-Mart representatives about putting a fence around the store's garbage dumps and installing parking lights away from residences.

Draper City Manager Eric Keck said the city solved its initial qualms about the retailer through open and ongoing discussions. But he noted local grocery stores have seen a decrease in business since the retailer moved in.

Smith's suffered the most, losing nearly 30 percent of its market share, Keck said.

"I was expecting worse. You read a lot about Wal-Mart and how they just throw their weight around," Keck said. "But they bent over backward for every concern that we raised about the building fitting into the hillside."

That spirit of compromise forged a good relationship between residents and Wal-Mart, said Bill Rappleye, CEO of the Draper Chamber of Commerce. Since moving in, the retailer has donated more than $1,000 to local arts in Draper and has put Wal-Mart representatives on the city's Chamber Board.

|

"If they just come in and reap all the benefits and five years down the road close their store and walk away with bags full of money, I don't think any citizens want to see that happen," Rappleye said. "It's important for businesses to put down their roots and get involved with the community."

Wal-Mart recently started an ad campaign to spread the message that the chain is willing to work with communities. Moreover, Berger said the ads aim to clarify misconceptions about the company that have biased residents against Wal-mart.

One of those bits of misinformation, Berger said, is that Wal-Mart pays low wages and offers no health benefits. On average, Wal-Mart employees make $9.68 an hour, and both full- and part-time employees are eligible for insurance, he said.

"We just feel that it's time that we set the record straight and provide people with the facts about our company," he said. "There's been so much misinformation out there, it's become almost urban legend."

E-mail: estewart@desnews.com; dsmeath@desnews.com; nwarburton@desnews.com