Every 15 minutes for almost 15 hours each weekday, the Route 22 bus runs up and down State Street, pausing for passengers at 14 stops.

There's always the low rumble of the engine, the squeaky whine of the brakes. Doors open and then close with a slap.

Just a few seats behind the driver sits 18-year-old David Felipe Gomez in a plaid shirt and jeans, a tiny ring piercing his lower lip. One seat away is Chris Hopkin, wearing a yellow tie and polished shoes, and he rests one leg on the seat as he scrolls through a handheld computer.

In the Salt Lake area, an average of 56,000 people ride the bus each weekday. Most follow an unspoken code: You don't sit next to someone if an empty seat is available, and you generally don't talk or make eye contact. Riders will stare out the window, close their eyes, flip through a book or look at their cell phone.

Anywhere from 12 to 50 people ride the Route 22 bus at 8 a.m. It leaves each morning from the 6400 South TRAX station in Murray and ends at the Salt Lake City Intermodal Hub at 600 West and 200 South.

The bus brings people together who might otherwise never cross paths. Sometimes, schedules and lives will intertwine. Or people will get off the bus, to have their seats taken by others.

But what do they know of each other?

The driver

About five minutes before he's scheduled to leave at 8 a.m., Chuck Ackerson wanders outside the bus to talk with Tom Brotherson, a fellow driver who goes by "Tom Tom." Brotherson drives the 8:15 bus, just after Ackerson.

For more than 30 years, Ackerson has worked as a bus operator for the Utah Transit Authority. It's a job he says he fell into but enjoys. Toward the end of the Vietnam War, he was in a specialized program to become a pilot. But then the war ended, and "they didn't need us anymore," Ackerson says.

He took a job as a bus driver because he had a young family and needed to provide.

His mother and father are buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His father was a technical sergeant during World War II. His mother was eligible for burial in Arlington because of his father's service.

"I used to sit on President Taft's grave," says Ackerson, who grew up in Virginia but came to Utah after high school.

Ackerson and his wife met 34 years ago at Brigham Young University. They raised nine children. One is an optometrist now, and another is a speech pathologist.

On the bus, Ackerson is generally quiet, but he responds pleasantly when talked to. One morning, when the bus is nearly empty, Ackerson begins humming the hymn "How Great Thou Art" to himself.

He says he doesn't remember names, but always faces.

A daily routine

About five minutes before the bus is scheduled to leave the TRAX station, Jennie Gerona has taken her seat, just behind the driver. She wears a lot of pink and red and usually carries a book. She doesn't talk to other passengers. She just smiles.

Ackerson greets Gerona, calling her "Smiles" or "Harry Potter," depending on the book she has.

For six hours each weekday, Gerona volunteers at the Murray Heritage Center, which provides socialization opportunities for the elderly.

She rides TRAX from her home in Draper to 6400 South, then takes the bus one stop to the Heritage Center, located around 6100 South.

Gerona, 31, lives with her parents. She has a learning disability, in addition to attention deficit disorder and a sensory impairment, she says. "My short-term memory is not good, and my long-term is better." She says she has a lot of friends with special needs like herself.

One day, Gerona wants to travel to Puerto Rico, where her grandfather was born. She wears an amethyst ring that her grandmother gave her two months before she died. "My dad said we could have been twins," Gerona says of her grandmother.

A kind of freedom

Tony Bodne is taking the bus this fall day because his car is in the shop, and he has to attend a heavy-duty mechanics class. Gerona is the only other person on the bus at this moment, but the two make no eye contact. She sits at the front, and Bodne finds a seat on the back row.

He spends much of the ride coloring designs on his baseball cap.

Bodne grew up on an Apache Indian reservation in Arizona that had only a post office and small Catholic school. He says he used to raise quarter horses and competed as a jockey in races. Adorning his blue jeans is a 4-inch wide silver belt buckle, outlined in gold, that says "top jockey."

From 1986 to 1989, Bodne served in the U.S. Navy. He was based in San Diego and shipped out to Hawaii then Florida.

That was the start of a career of wandering. After leaving the Navy, he "packed up a little stuff, peanut butter and jam sandwiches, and hitchhiked," he says. "I'm just like a free bird."

His plan: stay in Utah a few more years, and then go to another state. "I don't mind being like that," he says.

Long experience

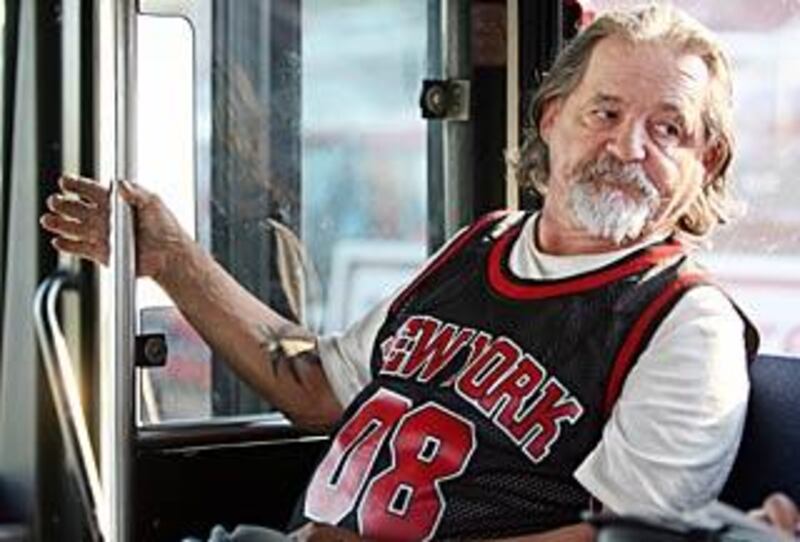

About midway through the 8 a.m. route, Rulon Scott boards the bus and sits in the seat nearest the front door, right across from where Gerona had sat earlier.

During the winter, Scott, 64, works as a cab driver in Salt Lake City. In the summer and fall, he says he just bums around. "All my time is spare time now," says Scott, who has a deep voice and gravelly laugh.

On his right forearm, he has a green, slightly faded tattoo of a marijuana leaf. "Many times I wanted to smoke my arm," he says, his eyes sparkling with amusement.

Four years ago, Scott's wife of 34 years died. They raised nine children.

"I'm from the old school," he says. "You stick it out whether you like it or not."

Scott spent four years in Vietnam as an Airborne Ranger. He was shot in the chest and his leg. A long scar runs down his stomach. It took almost a year to heal, he says.

He collects a military pension. But he says, "If I had known in '65 what I know now, I'd be a Canadian. Back in those days, when the country says you go, you go and don't question."

Then he reflects: "If it all ended tomorrow, I'd say I had a good time. But I'm not too sure I'd do it the same. I made some boo-boos along the way."

College bound

Laura Michie is always dragging a small black suitcase with her. It has a Salt Lake Community College logo and is stuffed full of books and papers.

Once she's maneuvered the suitcase on the bus, she always sits in the seat behind the bus driver with a heavy plop, the suitcase resting between her legs. She wears a green, puffy coat and white tennis shoes.

Michie takes the bus to school almost every weekday. Sometimes she'll start a conversation with the person who sits across from her. But she didn't talk with Scott the day he rode.

At age 50, after raising four children, Michie is going to the community college to earn a teaching degree. She says she wants a "decent job with benefits."

Going to school has given her confidence, she says. "It's been worth every minute I've had to struggle through."

Just a few stops after Michie boards, Alan Nordgren takes a seat toward the middle of the bus. He doesn't interact much with the other passengers and instead sits quietly.

Nordgren, 28, is working toward an English degree at the community college. Since birth, a degenerative retinal disease has been stealing his sight, and last year, he was diagnosed as legally blind. Someday, he hopes to become a college professor to help support his wife, Lynette, and their three kids.

"I have faith that everything will work out all right," he says.

The suits

Pat Larter boards the bus at the 6400 South TRAX station, taking a seat near the front of the bus. He wears glasses and is dressed in black and gray. He doesn't talk with his fellow riders. He just observes.

For 30 years, Larter worked as an engineer for the federal government. Now he teaches math at the community college. It's a job he says he enjoys more than engineering.

Hopkin, meanwhile, has an hourlong commute each morning. He'll take the bus from Orem, transfer to TRAX, then take the State Street bus to the Eye Institute of Utah in Murray, where he's doing a three-month rotation for optometry school.

To save money, he's living at his parents' home in Orem with his wife and 19-month-old child. He says he takes the bus because it gives him time to study for board exams.

"The commute is killing me as far as spending time with my kid," he says.

Learning English

Each morning, a group of people will exit the bus about 2400 South to go to English classes at the Granite Education Center. They include Gomez, who is from Colombia; Foroog Fhalili, from Iran; and Kenia Santiago, from Mexico. They talk to each other, but they don't interact much with passengers such as Larter, who sits nearby.

A group of Russian women also boards the bus together to go to ESL classes. They speak no English, always sit near the front of the bus, and sometimes get into fast-paced conversations. One has eyeteeth capped with gold.

Fhalili, a petite woman who often wears a head covering, nods at the driver with a slight smile when she boards, then takes a seat near the center of the bus. She sits up straight and clutches a bag on her lap with both hands.

She has lived in Utah for four years and has four children, one of whom lives in the state. "Utah is very small, but you live very good," she says.

The route

Paths that cross, space shared in a daily routine. The Route 22 bus continues up the street, and people get off and go their individual ways. Other passengers board, glancing at the faces, and then they find a seat.

E-mail: nwarburton@desnews.com