It's hard to say if John Matson was a dealer or a hoarder. What do you call a man who owned 55,000 antiques, so many old chairs and buffets and tables and desks that he piled them as high as the ceilings, so much stuff piled on top of another, the legs of the chairs jumbled together with the legs of the tables, that it was impossible, eventually, to walk across the rooms of his gallery.

Matson is 89 now and resides in an assisted living facility in Liverpool, England. A couple of years ago, the things he had collected over 40 years were liquidated; then most of it — 40,000 pieces — was sold to Salt Lake antique dealer Scott Evans.

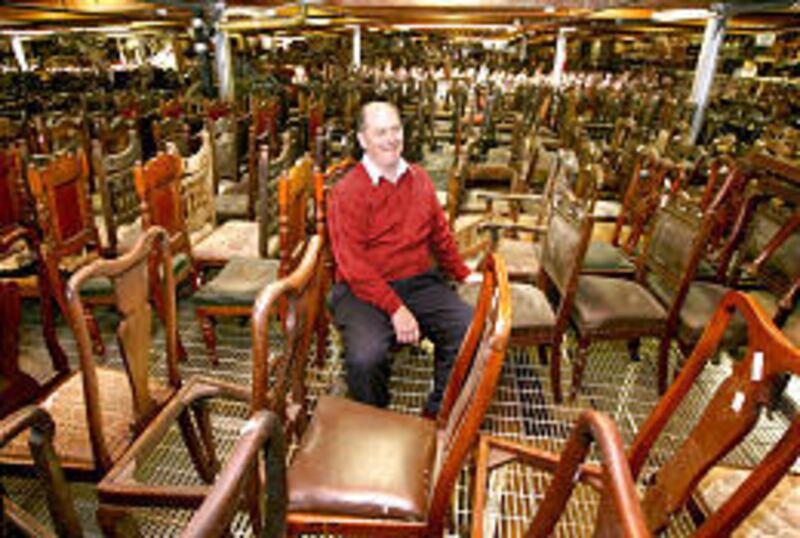

Evans has since moved the furniture to a warehouse on 600 South. He says it's the largest collection ever sold at one time, and he figures he now owns the biggest antique store in the United States. Euro Treasures, the name Evans gave to the collection, takes up 85,000 square feet in a warehouse that once stored tractors. There's so much stuff that the warehouse isn't big enough; nine additional 40-foot shipping containers sit out back waiting to be unloaded.

Nearly all of the furniture in the warehouse comes from England. One can imagine thatched cottages and drafty old estates, dukes sitting near sideboards having a spot of tea. There is a lot of Victorian this and Georgian that, most of it dark mahoganies and walnuts and oaks. There is an Elizabethan court cupboard from the late 1550s, a pub bench from 1620 and a hand-carved rosewood Regency secretary from 1840.

Evans recently sold the secretary for about $60,000 to a woman in Ogden. He's confident that there is enough wealth and enough interest in antiques in Utah that eventually — maybe it will take him 10 years — he'll sell all of the collection, mostly to people in state.

Right now, though, it's furniture as far as the eye can see. "From here to the back, we've done the Matson thing," says Evans, meaning that while some of the furniture has been placed in rows, a lot is still just buried behind and under everything else, with no access. "There's a million and a half dollars worth of stuff from here to the wall. It'll take us three years to get to it."

It cost about $7 million and took 18 months to buy, package and ship the stuff from Liverpool. Sixty thousand dollars in cardboard alone, most of it now sitting in the warehouse waiting to be reused. The antiques started arriving in Salt Lake City in June 2004; the last container was hoisted into the backyard of the warehouse in September 2005.

Evans first met Matson 22 years ago on one of his regular trips to England to buy items for Salt Lake Antiques, the store he owns at 300 South and 300 East. Matson's eight-story Theta Gallery, on Parliament Street in Liverpool, was quite orderly in those days. And England then was full of antiques to buy.

"Thirty or 40 cars and trucks a day would drive up with five or six pieces of furniture they'd want to sell," Evans remembers. Some of these would be families hoping to unload grandma's mahogany occasional table and her tea set, but mostly it would be "pickers" who had found a good deal at an auction or by going door to door around the English countryside.

"In 25 years it's completely dried up," Evans says about the availability of English antiques. Old stuff is harder and harder to come by in America as well, he adds. Sure, "old" is a moving target that now includes huge chunks of the 20th century, but antiques from earlier centuries are a finite resource, like coal and land. Not that the antiques disappear. "But once it ends up in 'strong hands,' " Evans says, "you won't see it again" because the stuff just gets passed along to children.

As for Matson, as the years went by he eventually chose to sell less and less of his inventory until all eight floors of the former warehouse were stuffed full.

"He was always a little eccentric," remembers Steve Swainbank, an antique dealer in Liverpool. "It didn't matter what it cost, he'd buy it. He would pay extraordinary amounts even if it wasn't worth it." Toward the end of Matson's career he sometimes wouldn't let buyers in the door. Evans remember Matson as a tall man with long, straggly hair and tattered sweaters. "And a parrot on his shoulder," Swainbank adds.

About 15 years ago, kidnappers captured Matson, took him to his home, placed a plastic bag over his head and demanded information about where he kept his money. They eventually got away with 100,000 pounds cash and were never caught. After that experience, Evans says, Matson became even more of a hermit.

A few years after that, while getting into his Mercedes one day, police questioned him because they thought he was breaking into some rich person's car. After he argued with them they threw him in jail. "Later they sent social services to check up on him and they found he'd been sleeping in his tub. There was nowhere else to sleep, there was so much stuff packed in there." Not long after that, competency hearings were begun. They stretched on for nine years, during which time the gallery was closed for business.

Evans says that some folks in Liverpool were a bit miffed that an American bought all of Matson's antiques. What he told his critics was this: "My ancestors sailed from the port of Liverpool. You people persecuted them and drove them out for being Mormon, and they left with nothing. I'm here to get our stuff back."

When Evans first was given access to Matson's gallery, he found rooms so stuffed with furniture that it took three days to clear a path to the elevator. The top floor of the gallery, with its two-story vaulted ceiling, took four months to empty.

"It was like mining," Evans says. "You're digging and digging and you hope you reach the mother lode." It took eight months to haggle over the price of each piece with Matson's former partner, who had purchased the collection from Matson's brother and sister.

Now that mountain of furniture sits in a chilly warehouse in Salt Lake City, where a stroll through the cluttered aisles presents a history lesson on the evolution of furniture and the appetites of Englishmen for exotic lumber. Over here is a crude coffer — a simple chest for storing dowry items like blankets and linens, before carpenters had figured out how to make drawers. Over there is a fancy bird's-eye maple armoire made by Gillows and Co., cabinetmakers to the queen. Evans employs eight furniture restorers to fix the pieces that have dulled with age. Upstairs are the chairs, some 1,200 of them, lined up, as Evans says, like the Terra-Cotta Warriors of China. Rows and rows of Regency and Victorian, royal and country, a convention of chairs just waiting for people to sit in them. And, nearby, a pile of chairs still waiting excavation.

Yes, laughs Evans, a few people have hinted that maybe he's as obsessed by antiques as John Matson was, especially since, before buying the collection, Evans had planned to retire to a condo in Hawaii. "But I liken it to this," he says. "You're a baseball player and you're playing triple-A ball in Dubuque and you're happy. And then you get called up to the majors."

E-mail: jarvik@desnews.com