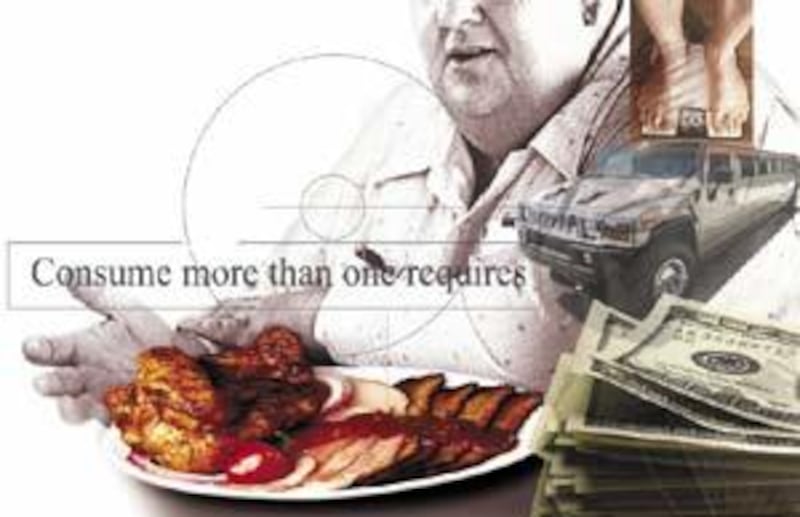

The word has an antiquated feel to it. We picture a Dickensian character, his vest barely able to cover his belly, sitting in front of a large platter scattered with the detritus of dining. Perhaps it is the over-the-top nature of the word itself that makes us sure that gluttony is the one deadly sin that never applies to us.

But gluttony, say scholars and theologians, is as modern as McDonald's — and Game Box and overdraft protection.

It's all about excess.

The trick is figuring out at what point we cross the line — from being a person who has simply reached for another glazed doughnut, from being a nation that invented the SUV, from being a global economy that prods its citizens to always buy more. Where have we crossed the line to become a people who individually and collectively are guilty of something that can be categorized as a sin?

In the beginning, gluttony was strictly about food and drink. And, in fact, technically it still is, says Mary Louise Bringle, a professor of philosophy and religion at Brevard College in North Carolina and author of "The God of Thinness: Gluttony and Other Weighty Matters."

The etymology of the word, she notes, refers to "that which you take down your gullet." Gluttony, she adds, was never about the palate. "It's not about enjoying the food. It's about using it as an anesthetic." Gluttony dulls the senses; that's why the first few bites of ice cream taste good, and the half-gallon ingested in one sitting "doesn't taste at all," Bringle says.

And yet the Catholic Encyclopedia, published in 1909, did argue that "it is incontrovertible that to eat or drink for the mere pleasure of the experience, and for that exclusively, is likewise to commit the sin of gluttony." That interpretation has changed over time, says Susan Northway, director of the office of religious education in the Catholic Diocese of Salt Lake City. Today, she says, Catholics view gluttony as the opposite of temperance, not asceticism.

Gluttony is now seen by society at large as a bad health choice — or sometimes, if we're more forgiving, as a matter of metabolism or an "issue"; at worst, like most of the seven deadly sins, it's seen as a character flaw. Ours is an age when the Food Pyramid and Freud have taken the place of Dante's Circles of Hell as the reference point for gluttony. We're more comfortable seeing overeating as an addiction, over-imbibing as a disease, excessive shopping as a weakness or just a credit-rating problem. In America, if we think of gluttony as a sin, it's often with a touch of irony; consider the dessert called Chocolate Decadence or, for that matter, that old standby Devil's Food Cake.

But gluttony as sin makes sense, says professor Rodger Bufford, who teaches psychology at George Fox University, a Quaker institution in Oregon. Overeating can hurt our health and therefore, by extension, can hurt others, including our families and everybody else whose insurance rates go up because we over-indulged. And "at a deeper level," Bufford says, "I think it affects our relationship with God."

Whatever we focus on obsessively, he says, "in a sense is a false god for us. At some level or other we're saying, 'This is the most important thing in the world to me.' "

There are countless ways to live "out of proportion," Northway says: owning 60 pairs of shoes, sending text messages too often, running too much, taking showers that last too long, being the kind of person who never puts boundaries on what they ask of other people.

Like all of the seven deadlies, gluttony is not a stand-alone sin, and it's sometimes hard to tell where gluttony stops and greed or pride begins.

"The irony of gluttony," says Neale Donald Walsch, author of "Conversations with God," is that we imagine at first we are grabbing all the happiness we can grab in its many varied forms. But the truth is that we are pushing it away from us. Gluttony never results in long-term happiness."

Gluttony, Francine Prose notes in "Gluttony," part of the Seven Deadly Sins series published by Oxford University Press, is seen as a "gateway" sin. Start overeating and drinking too much alcohol and who knows what will happen next. Prose quotes Aquinas, the 13th century theologian, who listed six "daughters" of gluttony: "excessive and unseemly joy, loutishness, uncleanness, talkativeness, and an uncomprehending dullness of mind."

Gregory the Great, who came up with his famous list of the seven deadlies in the sixth century, outlined the ways a person could be gluttonous: too soon, too delicately, too expensively, too greedily, too much. If you spent too much time fussing over and preparing the food — what today we might call a gourmet — that was considered gluttony. If you thought too much about not eating — what today we call dieting or, at its extreme, anorexia — that was gluttony, too.

Americans, notes David Smith, professor of philosophy and religion at Central Michigan University, have a conflicted attitude toward gluttony. We can't get enough of trendy new restaurants and cooking channels, and we're bombarded daily with ads for bacon cheeseburgers and soda and beer. On the other hand, we're obsessed with losing weight and getting buff. We want both kinds of six-packs — and, either way, we're preoccupied.

In medieval times, gluttony was not associated with obesity (in fact the glutton was usually depicted as thin, owing to indigestion). But today we think of the glutton as fat — and the fat as gluttonous, although it's impossible to know whether gluttony was to blame.

"Now that gluttony has become an affront to prevailing standards of beauty and health rather than an offense against God," Prose writes, "the wages of sin have changed and now involve a version of hell on Earth: the pity, contempt and distaste of one's fellow mortals."

Lynne Gerber is getting a doctorate at the University of California at Berkeley's Union Theological Seminary and is writing her dissertation on Christian evangelical weight loss groups. They walk a fine line when it comes to obesity and sin, she reports. Most of the groups "think of gluttony as a sin, as disobedience to God, but they don't want to go so far as to say. 'If you're fat, you're sinful.'"

Americans eat 25 percent more calories than they need, "so there is a kind of excess behavior in the culture," says professor Lloyd H. Steffen, chaplain and professor of religion studies at Lehigh University. "A glutton consumes and doesn't pay attention to the bigger picture" — in this case the effect of overeating on pollution and land use. If we buy gas-guzzling cars, we're gluttons, too, he says.

Which brings us to the Rev. Daniel Webster's prayer. The Rev. Webster, who used to be spokesman for the Episcopal Diocese of Utah, is now spokesman for the National Council of Churches in New York City.

"This Lent, I shall pray that our country be healed of the sin of gluttony," the Rev. Webster wrote in a recent e-mail. "With 5 percent of the world's population, we consume 26 percent of the planet's natural resources. We, collectively, as a nation commit the sin of gluttony each time we leave on a light bulb in a room we are not using. Each time a carmaker offers a vehicle that gets 15 mpg and people buy it, our society commits the sin of gluttony."

If, in the end, we are uncomfortable thinking of gluttony as a sin, we might want to consider the ancient Greek take on it all. Gluttony in its classic formulation, says Steffen, "is not so much a religious term as a moral one" — an offense against the moral order. For the ancient Greeks, the moral life was the road to happiness. "And the way to do that was moderation."

So, how do you know when you've crossed the line? How do you know, in your own life — even if you aren't downing 13 pounds of spaghetti at the Alka-Seltzer U.S. Open of Competitive Eating — if you've become a glutton?

"Each person has an innate sense of what 'enough' is ... an inner guidance system that is infallible," says "Conversations With God" author Walsch. He imagines God talking to us: "If you only knew who you really are, if you could only hear me. Gluttony is not necessary for you to experience your truest joy."

Is there an eighth deadly sin?

Philosophers, poets, authors and theologians have written about the Seven Deadly Sins — lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, anger, envy and pride — and the damage that they do to the soul since the fourth century.

But what about in 2006? Is there another deadly sin that should be added to the list in modern times? Let us know what you think. E-mail your thoughts to the Deseret Morning News religion writers at respond@desnews.com. Please include your name, phone number and e-mail address.

Next week: March 19 — Greed

E-mail: jarvik@desnews.com