MONTICELLO — The children called them "sand hills," a name that in retrospect is one of the heartbreaking details about this town's not-too-distant past.

Surrounding the giant hills was a cattle fence, two simple strands of wire with plenty of space for a child to crawl through. So, the children played there, making forts in the hills of uranium mill tailings and in the contaminated water of the ponds and creek. And the grown-ups hauled away the tailings to make mortar for their houses, to pave their streets and to fill the sandboxes in their back yards.

This was in the 1960s and 1970s and 1980s, after the "uranium frenzy" of the 1940s and 1950s, and after the federal government abandoned the uranium mill on the south side of town — but before the government finally came back to clean up the site.

"It was a paradise for kids," Bruce Adams remembers.

After the uranium mill closed in 1960, he and his best friend, Alan Maughan, used to swim in the evaporation ponds. In 1966, when he was 16 and captain of the Monticello High School basketball team, Alan died of leukemia.

Forty years later, there have now been 24 leukemia deaths, 77 serious respiratory diseases and a total of 407 cancers — and counting.

"I have two more victims," said Adams on Tuesday when he ran into Barbara Pipkin at the courthouse. Pipkin wrote down the names — a woman and her son who had moved away from Monticello years ago.

Pipkin is a member of VMTE, the Victims of Mill Tailings Exposure, a small committee formed two years ago to carry the banner for the on again-off again battle to get the federal government to pay attention to the health problems of Monticello. They want the government to do a "dose reconstruction" that will determine, as Pipkin says, "what we were contaminated with and at what levels." That includes not only radiation but toxic chemicals, she adds.

This week the committee is having a victory of sorts.

Representatives from the Utah Department of Health, the federal Centers for Disease Control and several other state and federal agencies will be in Monticello to listen to resident concerns. The UDOH and CDC will also release their own findings about the town's cancer rates. The town meeting is tonight at Monticello High School at 6 p.m.

Townspeople aren't sure what to expect. But VMTE member Fritz Pipkin says, "They're not getting out of here telling us we don't have a cancer problem."

The committee isn't confident that the state and the feds have all the necessary data, because they are apparently basing their numbers on Utah Cancer Registry statistics. The problem, city manager Trent Schafer says, is that lots of people have moved away and may have been diagnosed in other states. And some states don't have cancer registries.

When the VMTE has asked the government for the names of former mill workers, they've been told that's classified information. Even the number of mill workers is classified, says committee member Steve Young, whose brother died four years ago of a rare cancer.

The Monticello mill once processed uranium for the government's nuclear program, including the Manhattan Project that created the bombs dropped over Japan during World War II.

The town itself — the land and the buildings — has been given a clean bill of health in recent years, following the U.S. Department of Energy's designation of the area as a Superfund site. The actual cleanup began in 1995 and was completed in 2000. Today the mill site itself is a grassy drainage area with walking trails. And the government, under the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, has awarded financial compensation to many uranium miners, mill workers and ore haulers.

But what about the families, asks the VMTE? What about the townspeople whose windows were covered in yellow dust from the mill's stack? The dust, Barbara Pipkin says, ate holes in the screens, and in laundry hanging on the line. What about the children who hugged their daddy's legs when he came home from work, wearing his contaminated street clothes? The workers weren't given special uniforms to wear, even though when the DOE came back to clean up the sites they had big protective suits "like space men," Pipkin says.

And what about her husband? Fritz Pipkin, who once swam in the mill's evaporation ponds and made forts in the tailings piles, was diagnosed three years ago with leukemia, at age 55. Last week he finished his latest round of chemotherapy, which required many trips to St. George.

Monticello residents want a treatment clinic in Monticello. They also want a cancer screening facility, and they want monetary compensation for all victims.

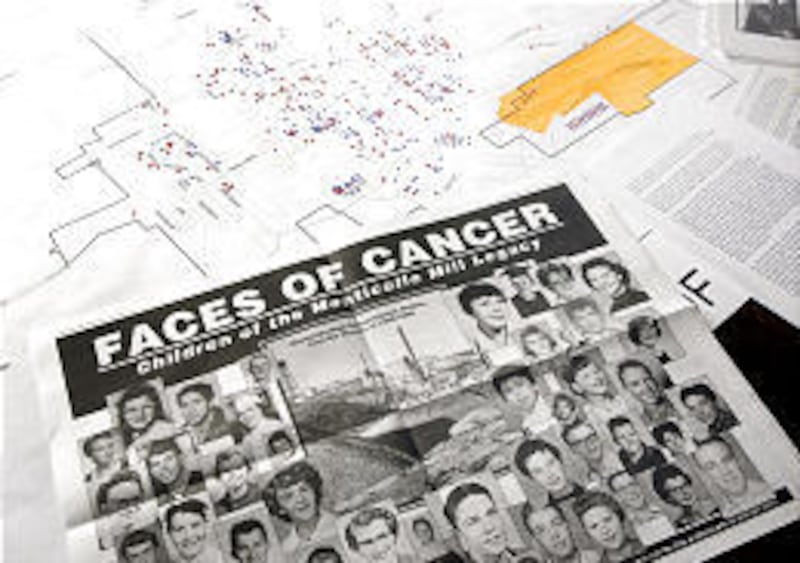

The Pipkins have created a map of the town, full of red and blue dots, each one representing a cancer (the blue dots from a 1993 health survey conducted by townspeople, the red dots from a 2005 survey).

"That's an entire family," says Barbara, pointing to one square with seven dots. Five people have died; two daughters are still alive. The Pipkins have also made a poster called "Faces of Cancer." It includes 52 students who attended Monticello High from 1956 to 1966. The Pipkins estimate that's one in every seven students.

VMTE member Craig Leavitt, 56, says that of his graduating class of 28, at least six have gotten cancer.

"Our question is, 'Why have they forgotten us?' " says Steve Young about the Department of Energy. "How many people have to die?"

E-mail: jarvik@desnews.com