SPANISH FORK — Richard Davis sobbed over the Spanish Fork High School PA system as he begged for any information about his missing daughter.

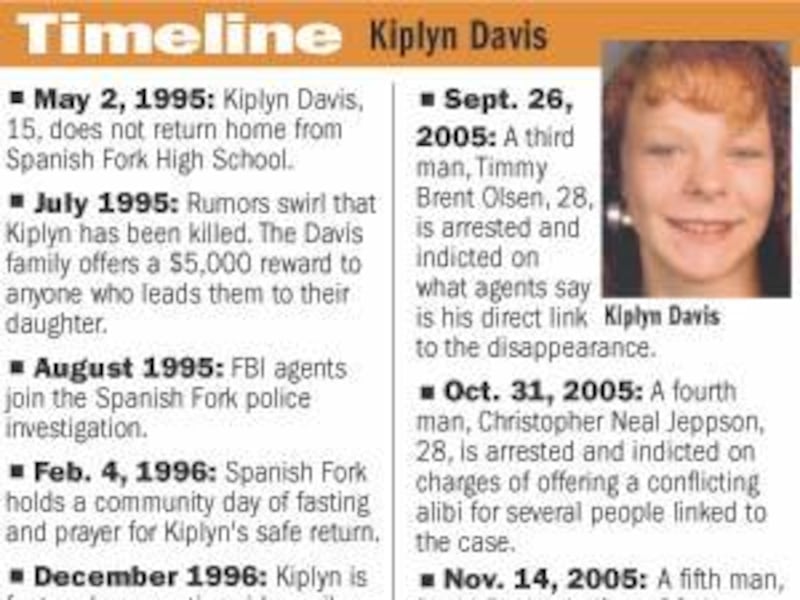

Fifteen-year-old Kiplyn had not returned home for two days. Police were treating her as a runaway, partly because she and her father exchanged harsh words that morning, May 2, 1995. An official search wasn't under way. Only family and friends were looking for her.

Desperate, Davis turned to the high school student body for help.

"If anyone knows where she's at," he pleaded over the school's speaker system, "please tell her I'm not mad."

Seniors Timmy Olsen, Rucker Leifson, Chris Jeppson and Scott Brunson likely heard Davis' quavering voice that day but said nothing. They and another man now accused of knowing about her disappearance continue to maintain a code of silence that detectives have begun to crack.

How such dark secrets could be kept in a small, congenial community like Spanish Fork still has authorities and residents baffled more than a decade later.

"How come it's been kept so quiet is something we're still trying to figure out," says Clark Caras, who grew up in Spanish Fork and has family there. "These kids weren't the Mafia."

Olsen stands accused of lying to FBI agents and a federal grand jury in connection with what happened to Kiplyn Davis. His perjury trial in U.S. District Court begins today. He also is charged with first-degree murder in 4th District Court in Provo.

A preliminary hearing on that charge won't be held until October.

Leifson and Jeppson also face federal perjury charges. Two other men, Brunson and Garry Blackmore, are charged with making false statements to authorities.

A missing persons poster of Kiplyn remains tacked to a wall in the lobby of the Spanish Fork police station. Police plan to leave it up "till we're done," says Lt. Brad Stone.

The rough start at home aside, Kiplyn arrived at Spanish Fork High School that May morning, her lively, flirtatious self.

Bobbi Freeman passed her in the hall between second and third periods. She was with some boys. Freeman doesn't recall who they were but says, "She was enamored with older boys like most 15-year-olds are."

Knowing Freeman was headed to Michigan on a choir tour the next day, Kiplyn told her to have a good time. That was the last time Freeman saw her.

Freeman didn't learn of Kiplyn's disappearance until the following day, when she received a telephone call in Michigan. She talked to Leifson, among others. He told her he was looking for Kiplyn.

Rumors about Leifson's involvement in Kiplyn's disappearance surfaced within days, as did a flurry of off-the-wall stories. Freeman says she asked him directly if he knew anything. He said he didn't.

Authorities believe Kiplyn left campus with Olsen and at least one other male friend, possibly Leifson. They have hinted that Leifson might be more involved than they have been able to prove at this point.

Richard Davis says he doesn't know why his daughter would have gone anywhere with them other than to get a soft drink at one of the local hangouts.

"It could have been her downfall," he says. "I don't know."

The not knowing has been hard on the Davis family. Though Davis at various times over the years saw some of the now-accused men around town, only one talked to him.

Jeppson showed up at the Davis home one night to "clear his conscience" before leaving on an LDS Church mission, Davis says.

"I felt guilty for the way I had talked to Kiplyn," Jeppson stated in a transcript of an interview with an FBI agent. Jeppson said he apologized for crude remarks he made to Kiplyn at school. He said nothing of her disappearance.

The Davises doubt the sincerity of the apology and don't believe Jeppson told them all he knew. He ultimately did not go on a mission.

"We just keep on thinking that one of those guys is going to soften his heart and talk to us," Davis says. "I don't think it's going to happen."

The five men have engaged in what federal prosecutors call a "conspiracy of silence."

Authorities are at a loss as to how the young man or men who may have killed the bubbly, red-haired sophomore and disposed of her body managed to conceal the crime all these years. Only now are details trickling out. Kiplyn's body has not been found, though authorities believe it is probably buried in Spanish Fork Canyon.

"We all kind of scratch our heads and wonder the same thing," says Utah County Attorney Kay Bryson, whose office will prosecute Olsen on the murder charge. "We have wondered ourselves how boys could do that. We have wondered at times when someone would acquire a conscience."

Spanish Fork isn't a town without a conscience. Residents are friendly and civic-minded. They turn out to place colorful petunias in the planter boxes on maple tree-lined Main Street or lay well-manicured sod at a city ballpark. Neighbors look out for each other. Violent crime is infrequent and murder almost unheard of.

Chartered by Utah's territorial Legislature in 1855, Spanish Fork is a bustling city, seemingly larger than its population of 23,000 suggests. The rodeo grounds anchor the town on one end, while a mix of shopping centers and fast-food outlets keep it hopping on the other. Construction trucks of all kinds rumble next to hay wagons on the wide main drag. Rows of new houses continue to gobble up one-time farmland.

Memorial Square is where families honor their dead with bronze plaques on a red brick wall or a paving stone. Kiplyn's name is not there. Nor is her body beneath the headstone at the city cemetery.

Spanish Fork residents find the secrecy surrounding her disappearance hard to understand in what they call a friendly, close-knit city.

"I think the community was shocked when the news came out. Disgusted and shocked, and it's still not settled," says Marie Huff, who was the mayor of Spanish Fork when Kiplyn vanished.

"I can't imagine young men keeping a secret like that," she says. "Always there's one that speaks up. I was surprised. A lot of people were surprised."

City Councilman Steve Leifson, a building contractor, says that despite residential and commercial growth, Spanish Fork still has "that hometown feel."

"This is really out of character for our town to have something like this happen," says Leifson, a cousin to Rucker Leifson's father.

Leifson is a prominent name in Spanish Fork, going back generations to Icelandic settlers who helped establish it. The Olsen family, too, is well-regarded.

"They're all good citizens," Steve Leifson says.

And they all know each other, or at least did a decade ago. They shopped at the same stores and went to the same churches and schools. They coached each other's children in baseball and other youth sports.

The Davises once attended the same LDS Church ward as Rucker Leifson's family. Richard Davis went to school with Rucker Leifson's father and did concrete work at his house before Kiplyn vanished.

Still, some among them apparently continue to harbor a horrific secret.

Rucker Leifson and Timmy Olsen were hardly secret society figures, at least not to their high school classmates and teachers.

"I didn't know them to be troublemakers," says Darrel Rolfe, a former school counselor who now works as the assistant principal at Spanish Fork High. "They were just students. They were just kids here."

Leifson was an affable and outgoing actor in the drama club whose monologue earned top honors at a 1994 competition sponsored by the Utah Shakespearean Festival. He had the lead role in the school play, Shakespeare's "The Tragedy of Julius Caesar." The play deals with guilt, the temptations of power and the influence people can have over one another.

Freeman recalls first meeting Rucker Leifson at a high school football game. Leifson introduced himself in a "silly" way with a funny name and accent, she says.

"He knew everyone and everyone knew him," she says. "He was very good with people."

Another classmate, Jared Parmenter, describes Leifson as bold and assertive, a leader among his peers who stood up for weaker kids.

"He wasn't evil. He wasn't a mean, spiteful, hateful person. He was a good guy," Parmenter says.

County Attorney Bryson says people aren't always as they seem.

"I think the intimidation factor has been pretty pervasive. You can't maintain a conspiracy of silence without some motivation. The motivation has to be self-preservation with some of these people, but it has to be intimidation with others," he says.

Freeman, who knew Kiplyn, Leifson and Jeppson but not Olsen, says, "Somebody was good at scaring people or keeping tabs on it."

Dave Boyack teaches physical education at Spanish Fork Junior High School and coaches the high school track team. Several of the men now facing charges were in his classes.

"It's been kind of tough for me to see former students involved in something like this," he says.

Boyack recalls Olsen as a "little bit of a character."

Like Leifson, Olsen was part of the school's drama club but not as an actor. He and Jeppson worked on the stage crew, whose members were known as "techies." They built props and sets and handled lights and curtains for plays. Olsen's role in the club was much like his place at school: in the background. His picture does not appear with his graduating class in the 1995 yearbook.

Former classmates describe him as aloof. He didn't gather with other club members around a bench in the drama hall before school. He hung out in the school's north parking lot with the rougher, cigarette-smoking crowd.

In divorce papers filed in 2003, a former wife described Olsen as having a bad temper, lying about his past problems and having financial debt.

Though what happened to Kiplyn Davis is shrouded in secrecy, not everyone's lips were sealed.

A federal indictment alleges Olsen told dozens of people at various times about his role in her disappearance, death and burial. Olsen has denied making any such statements.

Informants, some of whom will be called as witnesses in his perjury trail, related to authorities chilling comments they heard a sometimes drunken Olsen make over the years.

"I can make someone disappear. I've done it before. I did it once. I can do it again. I'm the only one involved in Kiplyn Davis' disappearance," Olsen has said according to a court affidavit.

But he also made statements that implicate another person. He told an informant that he and a friend took Davis up the canyon. Olsen said he and Davis fought and the other boy walked off. Olsen said he then "took care of Kiplyn Davis."

One informant told investigators Olsen stopped dating a woman in 1997 — two years after Kiplyn's disappearance — because she resembled Davis.

Olsen flashed his threatening nature to a woman who stopped dating him last summer. According to court documents, he told her he had killed before and wasn't afraid to kill again. "You, your child and your new boyfriend are on my hit list."

Before the federal indictments and murder charge, Richard Davis was willing to talk to anyone regarding his daughter, including his theories on what happened and who he suspects was involved. Now, he and his wife, Tamara, choose their words more carefully. They don't want to jeopardize the cases, not when they are so agonizingly close to perhaps knowing.

The Davises can now only hope the story unfolds in the courtroom. Maybe then will Richard Davis get the long-awaited answer to his teary plea of more than 11 years ago.

E-mail: romboy@desnews.com