PROVO — Student protests at Brigham Young University happen only sporadically, but the history of student activism dates back about a century and includes some colorful stories.

In 1910, for example, students took to the streets of Provo over the Prohibition issue, according to the book "Brigham Young University: A House of Faith," by Gary James Bergera and Ronald Priddis.

"BYU certainly has a history of student and faculty protest," Bergera said Friday. "It's not a real lively history, but it's still part of BYU's past and seems like it will be on into the future."

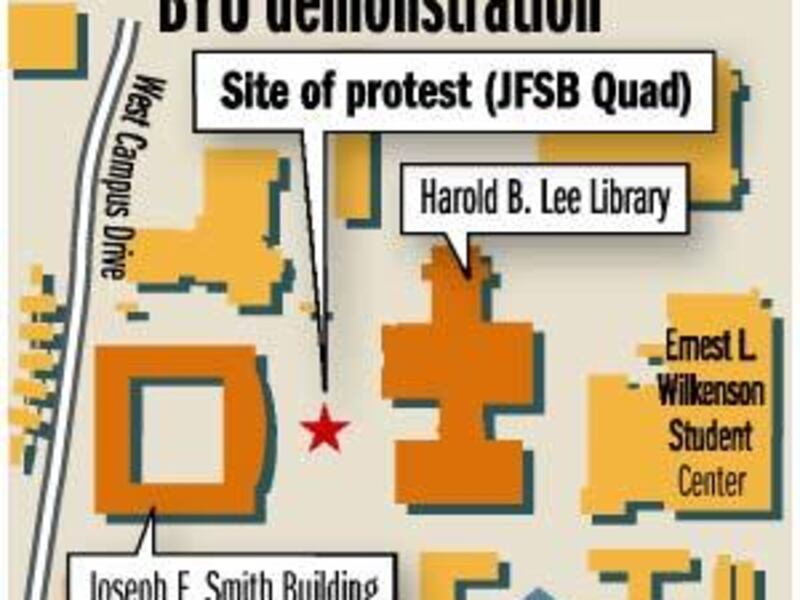

That future is now. The university approved a request this week by the College Democrats student club to sponsor a protest on Wednesday. The demonstration will object to the selection of Vice President Dick Cheney as the commencement speaker at graduation on April 26.

A second campus protest will take place the day of Cheney's speech — if administrators and students can agree on a location. A decision is expected by Tuesday.

Of course, BYU is known for its lack of protests, a reputation earned during the unrest of the 1960s when the campus was nearly devoid of the upheaval that paralyzed other American colleges and universities.

BYU earned national praise in publications such as the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times for its peaceful campus and well-behaved students, although a claim in a school-produced history that there wasn't a single protest march or anti-administration protest during the period is a stretch.

That history was written by Ernest L. Wilkinson, who was the university president from 1951-71 and a conservative whose tenure, perhaps not so coincidentally, saw a politically diverse campus move to the right.

In 1934, in fact, more than 60 percent of students supported U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal welfare acts, according to a poll conducted by the Y News, an early student newspaper.

In 1911, students demonstrated to oppose threats of dismissal made about three faculty members who taught evolution.

And in 1919, they protested in support of the League of Nations.

But by the 1950s, polls showed the student body overwhelming in support of conservative presidential candidates, a trend that has continued.

Wilkinson did regularly invite presidential candidates from both major political parties to speak on campus, which led to visits by Harry S. Truman and Lyndon B. Johnson. He tried to tamp down student activism at every turn.

During the 1960s, Wilkinson told BYU students in his annual address that participation in a serious disturbance would lead to dismissal. The tough approach wasn't one-sided: Students regularly gave his pronouncements a standing ovation.

But not all students toed the line. Late in 1968, 60 students war black armbands to a lecture by third-party vice-presidential candidate Curtis LeMay and disrupted his speech with spurts of applause.

The next spring, administrators told students to remove peace signs from dorm windows.

Then in May 1970, Wilkinson denied permission to students who wanted to circulate a petition calling for the gradual withdrawal of funding for the Vietnam War. A letter to the editor in the Daily Universe called the decision a double standard because a petition supporting the war had been allowed years earlier.

Wilkinson relented five days later.

Some of the unrest might have been generated by the toll on the BYU family. In Vietnam, 38 BYU alumni were killed, listed as missing in action or held as prisoners of war.

Conversely, there has been little publicity about at least two BYU alumni who have died in the Iraq war. Navy Lt. Nathan White died in a friendly fire incident on April 2, 2003, when a Patriot missile struck the F/A-18C Hornet he was piloting. Army Capt. Bill Jacobsen died in a mess hall bombing in Mosul on Dec. 21, 2004.

Wilkinson's successor, Dallin H. Oaks, now a member of the Quorum of the Twelve of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, called for less partisanship during his inauguration in 1971.

"I would like to suggest that Brigham Young University has no political objectives, only intellectual and spiritual ones," Oaks said. He added his belief that all people should have strong feelings about political issues but called for kinder, gentler discourse.

"I hope we can achieve a moratorium on the use of the words 'liberal' and 'conservative' on this campus. I am persuaded by observation and experience that the damage caused by the use of these words far exceeds the value of the communication they foster."

Those labels are alive and well in the current campus debate about Cheney, who might wish to be treated like another Republican vice president, Spiro Agnew.

There were rumors of a student demonstration to denounce Agnew before he spoke at BYU in 1969, but that protest never took place.

Gordon B. Hinckley, then an apostle and now president of the LDS Church, visited campus in 1969 and, like he said during a speech at BYU last fall, provided what Bergera and Priddis called "an unexpected voice in support of student pacificism."

"I have felt very keenly the feelings of many of our young men concerning this terrible conflict," he said. In defense of conscientious objecters he added, "A man has to live with his conscience, his principles, his convictions and testimony, and without that he is as miserable as hell. Excuse me, but I believe it."

Not all of the activity in the 1960s was political. One year, more than 2,000 angry students who wanted extended Christmas vacations assembled at the football stadium, burned the dean of students in effigy and attacked the school cafeteria with raw eggs.

Student protests have decreased in number since 1982, when students demonstrated against a campus visit by Gen. William C. Westmoreland, former commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, during the annual campus Military Week.

Large banners, anti-war flyers and black armbands confronted Westmoreland.

But protests have continued. Last year, with the administration's permission, about 200 students staged a campus protest to decry the firing of a staff member who had criticized the BYUSA elections process in letter to the editor of the student newspaper The Daily Universe.

One student held a sign that read, Enter to Learn and Learn to Shut Up."

"I'm glad it's happening," another student said. "It kind of makes me feel like I'm at a real college."

That protest took place on March 31, 2006. Over the next two weeks, three more protests that included students happened without university permission.

First, on April 6, a documentary filmmaker screened his film in a campus classroom after the student who invited him was told he couldn't.

Then, on April 10 and 11, the Soulforce Equality Riders demonstrated on and around campus, resulting in the arrest of a handful of students who joined the protests.

E-mail: twalch@desnews.com