After a long season of racing down the mountains of Europe and North America, Steve Nyman, the Utah-born-and-raised World Cup skier, has returned to Orem to unwind and let his body heal. He is sitting in a Barnes and Noble bookstore, but it quickly turns into an aerobic exercise. He changes positions by the minute, crossing and uncrossing his legs and squirming in his seat, clearly uncomfortable.

"I'm actually trying to stretch my legs," he says. "You just get beat up skiing."

You think football players take hard hits; try racing down the Alps at freeway speeds and taking a few falls along the way, working with only a net and helmet. Let's see, he has a bruise on the top of his tibia and the bottom of his femur, where the two bones actually slammed into each other somewhere in his knee. He has a hamstring pull and a hyper-extended knee from a training-run crash. He has compressed discs in his back, which he has had treated with homeopathic injections.

"I'm going to a chiropractor when I'm done here," he says. "There's going to be a lot of rehab this summer."

Racing in Europe from October to April took its toll, but in the process Nyman turned some heads. He finished 10th in the overall downhill standings and claimed two podiums — third place at Beaver Mountain, Colo., and first place in Val Gardena, Italy.

The latter was a monumental victory, although it was lost on most Americans.

"You wouldn't believe how hard it is to convince the media how big of a deal a World Cup win is," says Juliann Fritz of the United States Ski and Snowboard Association. It's the equivalent of winning a PGA Tour event or a NASCAR race, and it's a relatively rare occurrence for Americans, let alone Utahns. Despite Utah's reputation as a ski haven, with the World's Greatest Snow and an Olympics on its resume and decades of raising skiers, the state has produced only two winners on the World Cup tour — Ted Ligety (the 2006 Olympic champion) and Nyman.

"The sky's the limit," says U.S. coach Chris Brigham. "Steve can take it as far as he wants to take it. He has the ability and the head for it."

What makes the 25-year-old Nyman's performance even more encouraging is that downhill racers don't usually reach their peak years until their late 20s or even well into their 30s. The same downhill courses are used from year to year, giving experienced skiers a distinct advantage with their accumulated knowledge of the terrain, technique and tactics.

"Winning the downhill takes a lot of experience," says Brigham. "You see that in the results."

Nyman performed consistently well in only his second year on the World Cup. He stared down some of the world's most daunting courses this year and proved to be, if not exactly fearless (Brigham thinks it's not the right word), then aggressive. There is no ignoring the dangers of streaking down a mountain at 80 miles per hour, even for the most talented downhill racers.

"I think about it all the time; every time I'm in the gate," Nyman says. "I think, 'Why am I doing this?"' He faced his moment of truth as he stood in the starting gate at Kitzbuhel, Austria, the most notorious downhill on the tour — "the Super Bowl of DHs," says one veteran observer. "The mac daddy of scary DHs." It's steep, icy and fast. Many years ago, a veteran American skier eyed the gnarly, steep course as he stood in the gate at Kitzbuehel, then backed out and retired on the spot.

"I stood up there and thought, this is crazy; I don't want to do this," says Nyman. "But I don't want to be that guy everyone is talking about."

He pauses. "But I do it," he continues, referring to the downhill. "I love it. No matter what, even if you suck, you have a smile on your face at the finish. It's so fun."

Nyman is just what the doctor ordered for the U.S. ski team: a breath of a fresh air, the anti-Bode. At the 2006 Winter Games, Bode Miller was the Cloud of Turin, openly partying all night, even bragging about it and rubbing the team's (and America's) face in it. He was surly, selfish and loutish and performed exactly like a man who had been partying all night. He whiffed in five races.

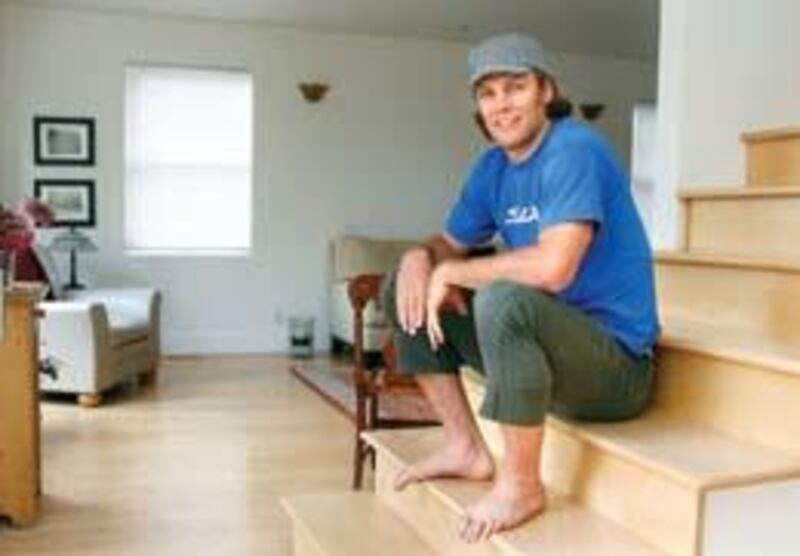

Nyman is open and friendly and leaves no doubt that he's glad to be skiing for a living.

"He's a great kid and fun to be around," says Brigham.

Nyman is a big, laid-back Orem High graduate, and beyond that good luck trying to pin a label on him. He's a long-haired, pony-tailed free spirit who believes in homeopathic remedies, cosmic energy, environmentalism and the Book of Mormon all at once. He goes to church on Sunday and goes to bars with his teammates to celebrate victories, toasting them with a Coke.

"I've come to learn what I want," he says. "People respect your desires. It's not as tough as people think (being a Mormon). It has to be that way. I travel with an eclectic group; it has to accept all types of people."

That comes easily for the easygoing Nyman.

"I've never seen him have any feuds," says Ligety, who has known Nyman for 10 years. "A lot of people have this image (of ski racers) as uptight. He's the complete opposite. He's definitely laid back."

But not when it comes to racing and skiing.

Put him in the starting gate, and laid back is replaced by intense competitiveness, which could drive him to be a medal threat in the next Olympics. His biggest challenge might be simply to stay healthy. Nyman, who at 6-foot-4, 215 pounds is one of the biggest skiers on the tour, missed most of three seasons with injuries, including two broken legs.

"We put our bodies through more strain than any sport out there. The G forces we develop on the new skis is incredible," he says, referring to the side-cut skis (like snowboards).

"They cut really hard. And I'm so tall it creates a lot of stress. There are more G's, and the vibrations going through the skis are intensified. There are times when it feels like my eyes are rolling down from the Gs."

Nyman is the product of a perfect storm of conditions to raise a ski racer. His father, Scott, was head of the ski school at Sundance Ski Resort. He and his wife, Becky, also an expert skier, and their four sons lived on the mountain year-round for 17 years. Nyman had it all: expert teachers in the house, brothers to push him and a ski hill in his back yard.

It was an idyllic life for boys. The mountains were the boys' back yard. They built dams, camped, hiked, built tree forts and, of course, skied. With few neighbors, they relied on each other for company and fostered close family ties. In the summer they were hired as caretakers for their neighbors' homes, mowing the law and weeding yards for resort owner Robert Redford, among others.

Becky likes to hold it over her husband that it was she who taught Steve and his brothers to ski. At one time she was taking three boys under the age of 5 skiing each Saturday, holding one on her lap as they sat on the chairlift. All four of the boys became excellent skiers, but only one of them had the taste for competition and the almost obsessive motivation to excel.

When he was 14, Steve, the second oldest of the boys, lost a race to two of his brothers and came home enraged. He hid under his bed "punching stuff" and swearing they'd never beat him again.

"What impressed me about Steve was that he loved it," says Becky, "and he was self-motivated."

Steve, who started skiing at age 2 and racing at 12, read magazine articles on ski technique and made notes on coaching advice and things he learned from reading. When he was 16, a coach asked him to write five goals. His five: Make the U.S. ski team, win a national title, ski in the Olympics, win a World Cup race and win a world championship. He has accomplished the first four.

"I found those goals about a year after he made them, and I thought, isn't that nice; he made goals," says Becky. "I was glad he was shooting for the stars, but how many kids does that happen to. I never thought it would happen."

A few years later, while sitting with her family in the Olympic stadium for the opening ceremonies of the Salt Lake Winter Games, she remembered Steve's goals. He had just made the U.S. junior world team. "Steve," she said, "in four years you could be in the Olympics. Wouldn't that be amazing?" Four years later he skied in the Turin Olympics.

Nyman's ascension to the top has been steep and quick, and he did it the hard way. Many of the top professional skiers attend private academies instead of public high school. Winter school, as it's known, runs from April to October, allowing students to concentrate on skiing in the winter. Most elite skiers also belong to one of several elite teams — Park City, Vail, Stratton. "Park City is the USC of skiing," says Scott. Few elite skiers hail from small teams.

Enter Nyman. He skied for the small team from Sundance and attended public high school. He finally began training with the Park City team after he got a driver's license, commuting after school and on Saturdays to hone his skills against faster skiers. Still, he attended relatively few camps and competed mostly in regional events. He never had the credentials to make the U.S. development team. He was, as Scott notes, "off the radar" for national team coaches.

He also was a late bloomer, still catching up with a big growth spurt in high school.

During the 2001-02 season, Nyman won a couple of regional races and seemed to indicate potential, but as Scott says, "Most kids his age had been noticed and picked up by a development team. If you were not picked up young, usually the window closes. You're written off."

Park City coach Rob Clayton lobbied the development-team coaches to put Nyman on the 2002 U.S. world junior (19 and under) team. Thanks to Clayton's efforts, Nyman made the team, but only as a discretionary pick — he would travel and train with the team, but he might not compete.

Translation: He might sit the bench.

But during training camp in Italy, Nyman caught the eye of the coaches. He not only was placed in the lineup, he won the gold medal in the slalom and silver in the combined. That performance qualified him for a spot in the World Cup finals in Austria. It was a bone thrown to world junior champions; they're not expected to be contenders against the best of the World Cup.

Nyman placed a remarkable 15th in the slalom and had the sixth-fastest second run. He was 20 years old. He never did make the development team; he skipped right over it. In a matter of months, he had gone from skiing for the Park City team to the World Cup finals.

Nyman seemed on the threshold of establishing himself as a World Cup regular, but the following winter he broke an ankle in a skateboarding accident. In 2003, he won the slalom at the U.S. national championships, but the following winter he broke his other leg the day after winning a Europa Cup race (skiing's equivalent of AAA baseball).

In 2005, he won the slalom again at the national championships, but he still wasn't fully recovered from the injuries. He was unable to train, and on race days he was limited to just two runs — an inspection run and the race. Because of lingering pain, he turned from slalom to downhill because it didn't put as much stress on his legs, and in 2005-06 he made the World Cup team full time in that event.

"It's nerve-wracking," says Scott, a former BYU assistant ski coach. "I want him to be a slalom skier. The downhill is crazy. I never thought he'd be downhiller. But you go where it takes you, I guess. His slalom this past winter started to come back. I predict he'll do well in the combined event (downhill and slalom). Part of it now is that he's been pegged as a downhiller."

Boosted by his showing this year, Nyman, who is single (he and Olympic champion Julia Mancuso broke up after dating a couple of years), will soon resume his off-season training regimen.

He plans to do most of his training in Utah but will spend some time with a personal trainer in Maui, as he did last year. His regimen in Maui includes, among other things, paddling a narrow long board (a 12-foot by 2-foot surf board) on the ocean from a standing position. Nyman will join the U.S. team for its annual training camps in New Zealand (August) and Chile (September).

"I'm home for the summer for the first time in a while, and it feels good," he says. "I want to explore the local area, just roam the mountains."

Nyman is a natural athlete. A few years ago a friend convinced him to try competitive cycling. He entered a Class C road race and won. The following year he entered the B class and won again. The year after that, he beat the A and B classes in the same race.

Nyman marvels at how his skiing career has fallen into place and credits it partly to the setting of a series of annual goals, from making the U.S. team to skiing in the junior world and World Cup competitions to coming back from injuries.

"I feel like setting goals put it in my head, and subconsciously it helped me find people who could help — like my trainer in Hawaii, like my chiropractor, Craig Buhler, like my technician," he says. "It was like this cosmic connection. Things are happening to make things happen. It sets the universe in order to do what I do."

During the off-season, Nyman also plans to continue efforts to lobby the U.S. Ski Team to do charitable work. This is partly because he wants to undo the damage done by Miller and partly because he has a compassionate streak.

A couple of years ago Nyman visited Haiti to perform humanitarian work for the Child's Hope Foundation. While helping to build an orphanage, he saw abject poverty and malnourishment, but also a proud, dignified people. He was so moved that he gave all his shoes and clothes away, returning home with only the clothes on his back and cheap flip flops on his feet.

"It opened my eyes," he says. "I don't complain about my life. I am here and should be happy."

Now he is urging U.S. ski officials to "give back." He wants skiing, which he considers to be cliquish and expensive, to be available to more people. During his travels on the Tour he says he has been saddened to see that the people who live in towns that host World Cup events are unable to ski.

"We tend to have events in communities that are supported by lower classes, but their kids can't ski," says Nyman. "I'm sure we can get sponsors to help them teach the kids to ski and give them a chance to ski. Racers could stay an extra day or have a day off to help the community. I love skiing. I'm fortunate to have it as my job. I want to see others enjoy it too.

"The ski team pulls in an insane amount of money to fund athletes. We don't give back. I'm telling them we should give back. They have been receptive. Especially with our tainted image, and the Olympics and Bode, they're trying to put something good out there."

Ask Nyman if he gets along with Miller, who recently left the U.S. ski team to train on his own, he pauses, and then pauses some more.

"Ummmm, it's tough," he says finally. "He was the example for the world, and it was not a good example. His image is what people's perception of the ski team is — partying, drinking. And all this fund-raising we're doing is going toward that? The ski team felt it; it was tough. The problem with that whole situation is it was all pegged on one person. Everybody else was amazing. I felt bad because Julia (Mancuso) and Ted's (gold-medal) performances were tainted by the hype around Bode. It was such a show he put on."

Nyman hopes to put another image out there of a young man who loves his sport and is grateful for the opportunity to ski for a living.

"Think about it," he says. "They close down the mountain so you can ski as fast as you want."

E-mail: drob@desnews.com