The man they call Sarge ambles down dimly lit hallways of the Regis Hotel where the trim is painted a bright baby blue, making his way up old creaking stairs and past small windows that offer little in the way of view and even less sunlight.

The carpets are old and worn. The air smells of stale cigarette smoke and the simple meals being warmed on hot plates behind closed doors. Empty garbage cans line the walls.

Sarge — James Sargent, 58 — hobbles to his room, his cowboy hat worn low over his eyes and his limp the result of a 1975 motorcycle accident. He opens the door.

"It's no Embassy Suites by any means. But it's nice. It's home," he says of the cramped space filled almost wall-to-wall by his bed and dresser.

It may not be home for long. The Regis and much of the rest of the block are now up for sale, their fate uncertain except that some sort of redevelopment is coming.

It's becoming a more common story in Salt Lake City's downtown and the surrounding neighborhoods: Areas that low-income residents once called home are undergoing a gentrification.

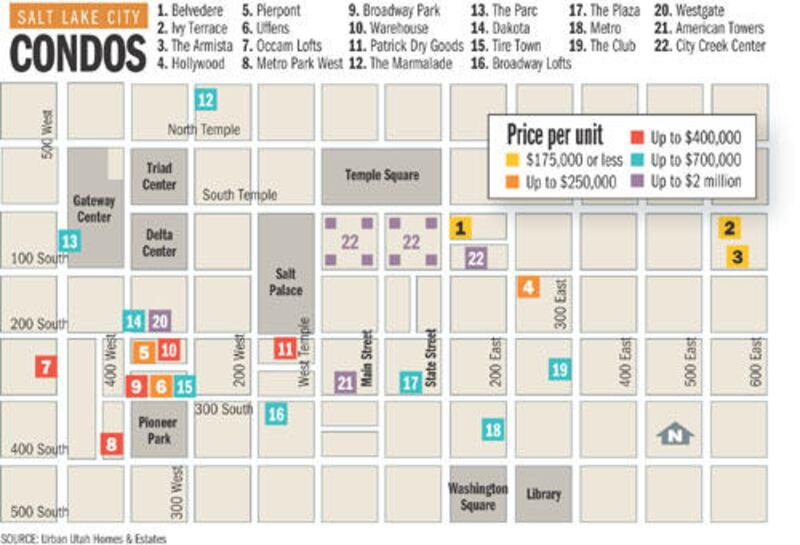

The Pioneer Mobile Home Park at 900 South and 200 East will be replaced by the Belmont Downtown Condos. A number of condo projects are popping up around Pioneer Park and elsewhere downtown.

And they're not cheap. Condos going into the Patrick Dry Goods building will start at $300,000. Howa Capital's Marmalade project, being built in a formerly blighted area of west Capitol Hill, will feature condos ranging from $284,000 to $695,000. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' City Creek Center will include dozens of high-end, luxury condos.

Downtown housing prices in the first quarter of 2007 are up across the board, with fewer homes available at the lower end of the price spectrum. As more high-end housing moves into downtown, low-income residents are moving out.

Tim Funk, a housing advocate with Crossroads Urban Center, says the need for affordable housing is outpacing the supply.

"You'd have to be completely dead not to know that housing has always been a critical problem," Funk said. "It's more of a problem than it's ever been, because we're not building any kind of appreciable affordable housing."

Slum sweet slum?

Sargent is one of about 120 people living in the Regis or next door at the Cambridge, two old hotels on State Street between 200 South and 300 South. Long past their heydays of the 1920s, the hotels, along with the now-closed Salt Lake Blue, have in recent years provided cheap, commitment-free housing to hundreds of residents.

"I don't have to mess with utilities or anything like that," Sargent says. "I have one bill. That I can deal with. It's quiet; it's old; it's very convenient."

The people who live in the hotels — known as single-room occupancy housing, or SROs — are there for a host of reasons. SROs operate much like any other hotel: You can rent your room on a weekly or monthly basis. Utilities are included. There are no criminal background checks and no leases.

And the rooms are cheap. Rents at the Regis and Cambridge are the same for every room: $85 a week.

Although residents of the downtown SROs are largely comfortable where they are, city leaders see a need for something new.

The Regis, Cambridge and Salt Lake Blue, along with a few surrounding buildings, have been owned by the city's Redevelopment Agency since the end of 2002. The RDA bought the property with the idea of future redevelopment but has kept the SRO housing open in the meantime.

Mayor Rocky Anderson has called the hotels "slums," and City Council members decided changes needed to be made.

The council, acting as the RDA's board of directors, essentially put up the for-sale signs on the block April 17 by approving the terms of a request for proposals, seeking developers to buy and redevelop the property. Preference will be given to developers who would restore the old buildings rather than tear them down. Despite efforts by council members Sren Simonsen and Jill Remington Love, historic preservation won't be required.

Residents don't know yet whether or when they will have to move. Given the choice, most of them say they'd rather not.

"After a year of moving around, I said, 'That's enough,"' one resident of the Regis Hotel said. "Next time I move, I hope it will be in a body bag."

City officials say they hope — but won't demand — that the new development will include some replacement SRO housing.

"As there tends to be more of a boom and more interest in people coming in, the value of properties goes up, and your neighbors across the street and next door are different," Councilwoman Nancy Saxton said. "So we have to look at, 'Is this the best location for subsidized or low-income housing, or is there a better location?"'

High-end development

At the end of the first quarter of 2007, no condos were available downtown for less than $100,000 and only four for less than $200,000, while two units were listed at more than $1 million, according to Babs DeLay, a member of the Salt Lake City Planning Commission and a real-estate broker who specializes in downtown residential sales.

Meanwhile, Utah State Tax Commission figures show that the mean adjusted gross incomes for residents in the two ZIP codes that make up most of the downtown, Central City and People's Freeway neighborhoods climbed by more than $10,000 from 1995 to 2005.

With the exception of a decline from 1999 to 2003 following an economic bump coinciding with the Olympics, downtown incomes have steadily risen from year to year. And advocates for low-income residents wonder whether the future downtown will include places for poor people to live.

In 2005, the RDA closed down the Salt Lake Blue because upkeep had become too costly and the building was deteriorating to unsafe levels. Even some of the residents doubt whether the other two downtown SRO hotels should stay open.

"Tear it down," said Greg Young, 50, who has lived at the Regis off and on since 1983. "It's just too expensive to fix it up."

Young does maintenance work at the Regis to help him pay his rent, and he said the building is full of old wiring that wouldn't stand up to code if it hadn't been grandfathered in. Much of the plumbing needs work, and if one resident turns on too many fans in the heat of summer, the whole building's power goes out.

Young's is one of the nicer rooms in the Regis. While most residents of the SROs have to share common bathrooms with their neighbors, Young's room has its own small bathroom. His windows are large and look over State Street.

Kicking back with a cold beer and dressed for bed on a recent afternoon — he works at night and sleeps in the day — Young acknowledges that "it's tight" to try to find affordable housing in the city, especially downtown, which is a must for many residents who need easy access to transit so they can get to work, doctor's appointments, the Veterans Administration and other services.

"People will find something. For some people, it will be hard," he said. But he added, "This is prime real estate here. Knock it down. Put something nice in here."

A community

The people who live at the Regis and Cambridge come from a variety of backgrounds and live there for a number of reasons.

Some are working their way out of homelessness. Others are patients of Valley Mental Health or have various emotional or physical problems. There are veterans of wars, seasonal or temporary workers, elderly people on Social Security, undocumented immigrants and erstwhile criminals.

Sargent has lived in Utah since 1971, and a good chunk of that time has been at the Regis. But at other times, he has lived in more traditional apartments and has twice owned his own home.

But Sargent has had his share of financial problems. Now he works seasonally for the U.S. Forest Service, doing everything from mowing lawns to assisting fire crews. He also works at the Interagency Fire Center. The Regis is home while he gets back on his feet financially. "When things get better, I'll move," he said.

Building manager Frank Richards, who also lives on the property, said many of the residents have few options. "We have a lot of people that can't relocate," he said.

One resident, Michael Whiteman, said he lives at the Regis because of a criminal background that he worries would disqualify him for other housing.

Richards said day laborers who live in the SROs can have streaks of regular work, followed by months of scarcity. When they fall behind, SRO managers allow them to pay what they can, when they can, knowing they will get caught up when the employment picture is better.

"No apartment would do that for them," Richards said.

Residents say some of their neighbors could afford to live somewhere else, but they like where they are, and they feel safe. They say they feel part of a community.

"Nobody ever goes hungry here," Sargent said.

What's next?

Advocates for low-income housing are divided over whether the State Street SROs should stay.

Rosemary Kappes, executive director of the Salt Lake City Housing Authority, said the buildings' time has passed.

"Their condition is horrendous," she said. "A building's time and life ebbs and flows."

Funk, at the Crossroads Urban Center, believes that the SROs need to stay. He worries the SROs are being disregarded because some city officials "think they're all crooks and shabby people" who live there.

He blamed the buildings' disrepair on haphazard management by the RDA and said they can be fixed up by taking it a piece at a time — new plumbing this year, new electrical wiring the next.

In its discussions of selling low-income hotel housing on State Street, the City Council is trying to find ways to make sure similar housing remains available in the city, but some housing advocates say it won't be enough.

Earlier this month, the council voted to contribute up to $3 million in RDA money to help The Road Home buy and renovate the Holiday Inn at 999 S. Main with the help of a $7 million donation from the LDS Church.

That project will include housing for people transitioning out of homelessness, as well as some SRO units. The project also will have housing for families with children, so there will be some minimal background checks to keep child-sex offenders out.

RDA staff members say they know of only three residents of the State Street SROs who would not qualify to live at the Holiday Inn.

Kappes believes the existence of such projects and other SROs throughout the city means that doing away with the State Street SROs won't diminish low-income housing.

"It sounds like it can be a substitute," she said.

But others say the Holiday Inn is too far from downtown — although it will be close to the State Street bus corridor and a TRAX station — and that with its background checks, it won't serve the same needs as the Regis and Cambridge.

"We think both things need to happen, that we need to preserve the SROs on State Street and they need to do what they're going to do on 10th South," Funk said. "We don't want the argument to be, 'Should they be on 10th South or should they be on State Street?' They should be on both."

E-mail: dsmeath@desnews.com