DEARBORN, Mich. — Greenfield Village teaches history the way Henry Ford thought it should be taught. Ford is rather famous for his "History is bunk!" quote. But, they will tell you at the village, that whole notion is taken out of context. It was not history that Ford disliked, but the endless string of wars, politics and dates that teachers tried to hammer into kids' heads.

Rather, Ford said, we should focus on how people lived, what they ate, how they worked.

At the dedication of his museum in 1928, he noted, "Mankind passes from the old to the new over a human bridge formed by those who labor in the three principal arts — agriculture, manufacturing and transportation."

Greenfield Village is the living history, open-air part of The Henry Ford, the extraordinary museum in Dearborn, Mich., that resulted from Ford's original attempt to collect at least one example of everything ever made in America. His passion for collecting eventually extended to buildings, and those buildings have now been arranged in a village that is somewhat reminiscent of a small New England town: a village green with its town hall, crafts shops and residences.

But the buildings were brought from many parts of the country and represent many different periods. And they are not simply buildings from the past. They all represent people "not made famous by virtue of birth or inheritance," rather, people whose achievements "made an impact on America through hard work, persistence, creativity, inner drive and a willingness to take calculated risks."

Some are names you will recognize; others represent ordinary people who lived exceptional lives. There are inventors and authors, as well as plantation owners, farmers and clockmakers.

Some buildings are reproductions or were built by Ford specifically for the park, but many are the original structures. In all, some 300 years of American history are represented, which makes the place an efficient way to discover the past.

Only in Greenfield Village, for example, do the Wright Brothers live around the corner from Thomas Edison's laboratory, and Robert Frost, George Washington Carver and Noah Webster are all neighbors.

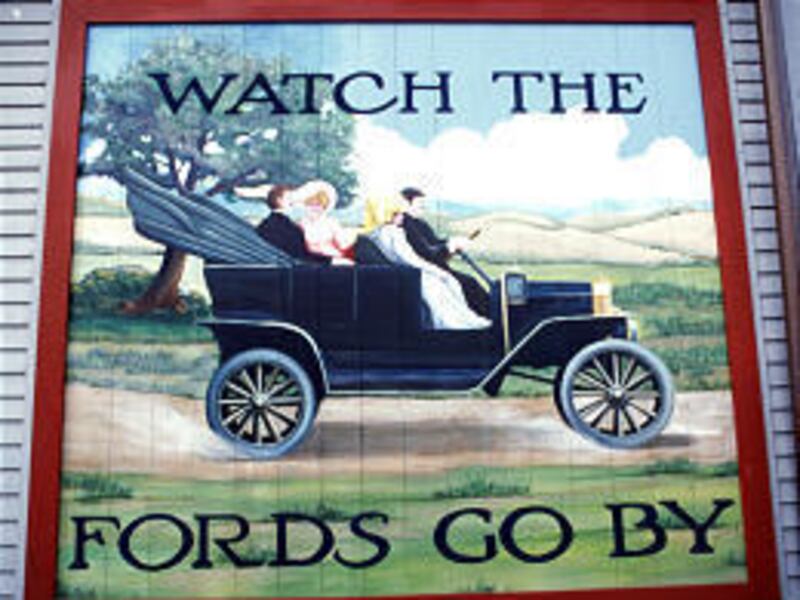

A fun way to start a visit to Greenfield is with a Model T ride around the 90-acre site. This not only introduces you to the layout of the village, but it also gives you an appreciation for Henry Ford's magnificent machine.

Other transportation options are available, as well. You can ride the train around the perimeter of the village. Don't be surprised if you have to stop somewhere along the way to let off steam and reduce pressure; this is a real steam-powered train. You can ride in a horse-drawn carriage along shady streets. All told, you can get a pretty good idea of how America moved.

But then, you'll want to explore on foot. Greenfield Village is divided into seven different districts, and each offers the sights, sounds and sensations of America's past.

In Henry Ford's Model T district, for example, you can see where it all started — the house where Henry was born in 1861. It is a modest, white farmhouse originally located several miles to the north of the village, where Ford grew up with his five younger brothers and sisters. He left the farm at age 16 — more interested in machines that agriculture. But he always loved the house and in 1919 restored it to the way it looked when his mother died in 1876.

Across the way is a reproduction of the Bagley Avenue shop where Ford built his first automobile — the Quadricycle. A small space for big ideas, Ford's machine turned out to be too wide for the door, and in order to take it out for a spin, he had to widen the opening with an ax.

Next up might be Main Street, filled with the homes, public buildings and workshops that graced a typical 19th-century town, and a place where you will surely identify with Sinclair Lewis, who said "Main Street is the climax of civilization."

There's a Town Hall, where you might be in time for a musical review. The Mary-Martha Chapel was built in honor of Ford's mother and mother-in-law; it's now used mostly for weddings. At the Liberty Tavern, originally a stop on the Detroit-to-Chicago road, you can get a meal based on authentic 1850 recipes that might include such things as noodles and peas, pickled eggs and cauliflower and rhubarb pie.

There's a Scotch Settlement School. Mrs. Cohen's Millinery Shop offers a look at the latest ladies' wear. Sir John Bennett's clock shop actually came from London and features Gog and Magog, mythical giants who tolled the Westminster Chimes each quarter hour from 1846 to 1929. The H.J. Heinz house pays tribute to innovation in food.

You can also see the house where Wilbur and Orville Wright grew up, perhaps even talk to them or their sister, who might be on the porch discussing their recent return from Kittyhawk. Across the street is their cycle shop, where they built and repaired bicycles when they weren't tinkering with airplanes.

And don't miss the Logan County Courthouse. One of the circuit-riding lawyers who tried cases in this courthouse around 1850 was Abraham Lincoln. Sit quietly and see if you can hear the echoes of those days.

For a livelier time, check out the Herschell-Spillman Carousel, where you can ride on hand-carved creatures that range from pigs and cats to horses and tigers.

You might also want to take in an 1867 baseball game played by the Lah-de-Dahs, based on an actual team by that name. The year 1867 means no glove and little else in the way of equipment.

In the Edison-at-Work district, you may catch the genius himself at work in his Menlo Park laboratory. From 1876 to 1882, Edison and his assistants created all kinds of doodads and amazements — including the phonograph, electric light, stock ticker, motion picture camera and mimeograph machine — in this very building.

Nearby is the Sarah Jordan Boarding House, where many of the workers lived. It was one of the first buildings in the world to be lighted by Edison's new electrical system. The only problem was that the light switch was across the street in his lab.

You will learn that Edison was only 32 when he invented the incandescent light — the same age as Ford when he invented the Model T and Wilbur Wright when he flew. Such young men to be doing such life-changing things.

Edison remained one of Ford's heroes throughout their lives. And, in fact, honoring Edison's achievements was a prime goal for Ford's museum.

In the Porches and Parlors district of Greenfield Village are more homes of the known and unknown, providing an interesting patchwork of daily life. There are cabins of black slaves and freeholders. There's a plantation house from the tidewater region of Maryland and the pre-Revolutionary War Daggett farmhouse from Connecticut.

There's the birthplace of William Holmes McGuffey, of the elementary school reader fame, as well as a cabin honoring the accomplishments of George Washington Carver, who was into peanuts, among other things.

There's the house where Noah Webster completed his 70,000-word dictionary; there's the house where Robert Frost wrote poems; there's the house where Stephen Foster made music. And just for the heck of it, there's a Cotswold cottage from England that was built in 1620 and taken apart stone by stone to be shipped here. Talk about a broad spectrum of living — you can see it all at Greenfield Village.

But maybe you want to see even more of how life was lived back before the industrial age and the automobile changed it all. Stop by the Working Farm district. Ford never forgot his farming roots and wanted to bring people closer to the soil, livestock and growing things at Greenfield Village.

At the Firestone Farm — the boyhood home of Harvey Firestone, who would become famous for his tires — you can see how farming was done in the 1880s, when wrinkly Merino sheep, Percheron draft horses, Devon shorthorn cattle, Poland-China pigs and Light Brahma chickens were kept out back.

Meals are cooked daily; chores are done around the house and yard; animals are given care; crops are grown. It gives you a good view of 19th-century farm life.

More working adventures can be found in the Liberty Craftsworks district. There you can see everything from glass blowing and pottery throwing to spinning, weaving, carding, printing, grinding and more. Demonstrations go on throughout the day; a variety of finished products is for sale, in case you want a souvenir; and if nothing else, you can enjoy the scenic millpond in the center of the district.

One final venue awaits: the Railroad Junction, reminiscent of the edge of an industrial town, where all roads lead to the depot. Added in 2000, the Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse is the newest addition to Greenfield Village and is the only working roundhouse in the Midwest, one of only seven working roundhouses in the country.

The Pere Marquette Railroad Turntable allows a locomotive to be turned in a small space. You might even be able to help. You might also get to stand in the inspection pit and see what a 50-ton locomotive looks like from the bottom up.

The Smith's Creek Depot at the junction is where Edison worked as a boy selling newspapers. It was originally in Port Huron, Mich.

By the time you've made it around the village, whether on train or foot or Model T, you will have a renewed appreciation for the little ingenuities that have changed the world. You will think differently about even mundane things such as hats and ketchup. You will respect anew people who followed their passion into the air, the laboratory, the fields or the library. And you will agree with Henry Ford: This is a pretty good way to learn some history.

E-mail: carma@desnews.com