One man was charged with stabbing his father to death on Father's Day. Another was arrested in the fatal shooting of his wife in an LDS church parking lot. A third is accused of killing his infant daughter by shaking and throwing her.

Because of the heinous and heartbreaking nature of the crimes, prosecutors have charged three Utah County men, Michael Kirsch, David Ragsdale and Victor Gardea, with aggravated murder. Each could face the death penalty.

In the last nine months, prosecutors have filed three aggravated-murder cases in 4th District — the most ever at one time — and the county is beginning to feel the financial crunch.

"With more capital cases filed, they're costing the county a ton of money," said public defender Gunda Jarvis, who just finished a capital case a few weeks ago that wasn't included in the count of three.

An aggravated murder case is potentially punishable by death and thus dwarfs the average criminal case in the amount of time and money required.

It's so expensive that the Utah County Commission recently approved spending $150,000 for the Utah County Public Defenders Association to assist with the cases of Kirsch and Ragsdale. The money does not go toward attorneys' fees.

Gardea's case is so new, the association is drafting a third request for additional money.

"We live in this great country that affords everybody the right to counsel, a right to due process," said Utah County Commissioner Gary Anderson, a former criminal defense attorney. "Justice is expensive. It's not just the defendant we're defending, we're defending our system, our system of laws, our way of life."

A capital case

The charge of aggravated murder is the only crime in Utah punishable by death.

For a murder to rise to that level, prosecutors must prove aggravating factors — such as killing several people, a child or a police officer, or that the murder was preceded by another crime like rape, sexual abuse of a child or robbery.

In June 2007, prosecutors charged Jason Putnam with aggravated murder, alleging that during the course of severe child abuse, Putnam caused the death of his 20-month-old son, Jordan.

Because Putnam had no money to hire an attorney, the judge declared him indigent and appointed a public defender. Public defenders also represented the four aggravated murder cases before Putnam and all three cases filed this year.

With each aggravated murder case the Public Defenders Association receives, it asks the county for financial help.

And since 2001, the county has authorized an average of $75,000 in sequential payments for each qualifying case.

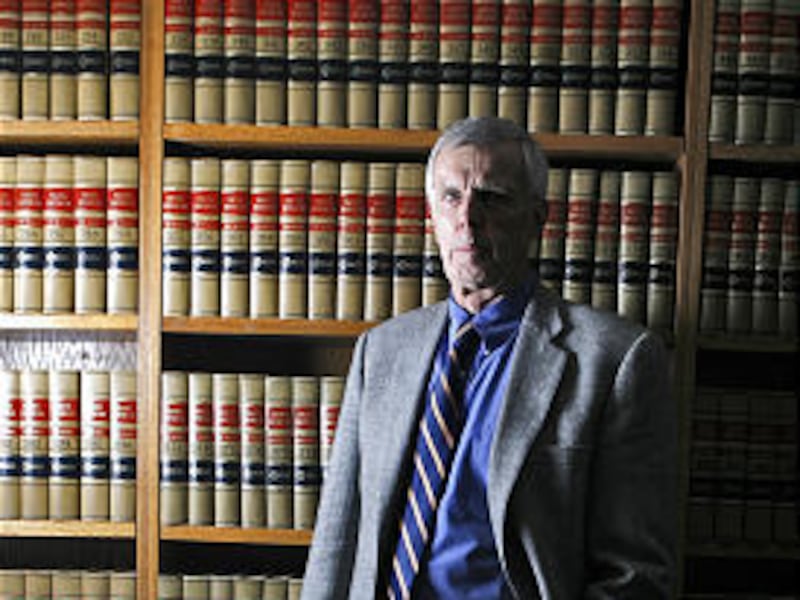

If the case can be resolved short of going to trial, the $75,000 may be enough, possibly even more than enough, said Tom Means, head of the Utah County Public Defenders Association.

Two recent capital cases — Jaime Velasco and Keith Lamont Morton — were each settled relatively quickly with guilty pleas, costing $67,524 and $34,807, respectively.

Negotiating murder

"We have a disproportionate amount of capital cases for our community," Jarvis said. "It seems like every murder we have is capital."

With an expanded aggravated murder code, adopted by the Utah Legislature in 2007 with HB228, prosecutors can now charge the death of a child as an aggravated murder — the charge Putnam faced and what Gardea now faces.

It's unlikely their cases would have been capital under the old statute, but they "fit very cleanly into the new language," Utah County Attorney Jeff Buhman said.

"I, personally, support the death penalty," Utah County Attorney Jeff Buhman said. "I think there are cases where the conduct of the defendant merits the death penalty, it's as simple as that. The fact that this is the highest a law allows is a significant stick, but that's because the crime is significant."

And with significant crimes, there comes a greater motivation to negotiate, Buhman said. No one wants the heavy punishment of death over their head.

"In my opinion, prosecutors in Utah have been very reasonable in their pursuit of the death penalty," said Kent Hart, assistant federal defender with the Capital Habeas Unit of the Utah Federal Defender Office — essentially a public defender for death-row inmates. "They've been restrained. But they keep the death penalty because they use it as a bargaining chip."

Buhman refuted the bargaining chip claim.

"It is a big stick, but we do not use it as a threat," Buhman said.

Deputy county attorney Tim Taylor said attorneys only file a capital case when they feel like they can prove all the elements of the crime.

"(Does) it ultimately end up being used as a bargaining tool? Absolutely, it just is," Taylor said. "But I don't think that's necessarily the reason that we do that. We have to feel like we can prove beyond a reasonable doubt the aggravating factors."

Yet, some defense attorneys question why the county doesn't file a charge of murder rather than aggravated murder, because a conviction nets almost the same consequences but saves the county tens of thousands of dollars in defense work.

Statistics from the state parole board show aggravated murder defendants who get life with parole serve, on average, a prison sentence six years longer than those who get the same sentence for first-degree felony murder — 28.4 years compared to 21.7 years.

Yet, the price tag for capital cases is thousands and thousands of dollars higher.

Death on the line

With any aggravated murder case, the American Bar Association mandates that defense attorneys must immediately begin a mitigation investigation, Means said.

"We have a whole litany of things that have to be met, for us not to be (seen as) incompetent," Means said. "While a prosecutor may be able to wait to declare his options, we can't. We have to get going."

A mitigation investigation is an in-depth look into every aspect of the defendant's life to avert death-row status.

If that investigation is not started immediately, it could mean a later appeal on grounds of ineffective counsel, Jarvis said.

The $75,000 received from the County Commission is immediately used to hire a mitigation expert and extra investigators, as well as pay for the travel of expert witnesses and travel of the mitigation specialist to conduct interviews.

"It's a huge amount of work," Jarvis said. "It takes a ton of money, a ton of time."

The first few weeks are the most intense because that's the time James Whitman uses to find information that might dissuade prosecutors from requesting the death penalty.

"We have to be on board the second it happens," said Whitman, a mitigation specialist out of Washington, who, along with his father, has worked with the Utah County Public Defenders Association for several years. "We have to be there the next day to make sure we don't miss anything."

Whitman interviews parents, siblings, grandparents, friends, schoolteachers, neighbors. He requests medical records from birth to present for the client, as well as medical records of parents and grandparents.

He's looking for anything. Fetal alcohol syndrome or a family history of depression. Traumatic childhood experiences. Problems at home.

"Basically mitigation ... is anything and everything proffered to get a sentence other than death," Whitman said.

Each case may require as many as 600 hours and cost a few tens of thousands of dollars just in the first few weeks, Whitman said.

"Without the death sentence, all you need is a guilt investigator and an attorney," Whitman said. "Just like the old Perry Mason."

But because death is on the line, the case also needs two death-case-qualified attorneys, psychologists, psychiatrists and another case investigator separate from the mitigation specialist.

Whitman estimated that hiring the experts, getting the records and conducting the interviews almost always depletes the $75,000.

And none of that money pays for overtime work by the public defenders like Means and Jarvis. The Utah County Public Defenders Association has 11 attorneys and more than 1,700 open cases — giving each attorney an average of 150, which stays the same when they get a capital case.

"We don't do it for the money," Jarvis said. "We're public defenders because we believe in the cause, the Constitution. Just having somebody charged with (the death penalty) gets me fired up and makes me want to work that much harder."

A new law

Before April 2007, any aggravated murder case filed in the state of Utah automatically had the death penalty attached.

However, in Utah's 2007 general legislative session, legislators approved SB114, which allows prosecutors an additional 60 days after the preliminary hearing before they file a notice to seek the death penalty.

With that notice, a case is changed from a first-degree aggravated murder to a capital aggravated murder.

"This change was not intended to either increase or decrease the number of times someone goes for the death penalty," said Paul Boyden, executive director of the Statewide Association of Prosecutors. "What it was designed to do is eliminate cases being treated like capital cases when they're not."

So now, rather than go through the case's entire life span with a capital mind-set, prosecutors can carefully consider their evidence and determine if they really want to pursue the death penalty.

"We don't want to be crying wolf in charging the death penalty when what we really want is life without parole," Boyden said. "It's a terrible mess to charge a capital case when what you really want to do is put somebody away for life."

Not only is it expensive, but it strains the resources of both prosecution and defense offices.

"Sometimes it's best to ... maybe even hold a preliminary hearing so that the actual facts of the case come out before you make the decision on the death penalty," Boyden said. "The majority of people are fairly thoughtful, and when more information comes out, you can give a better, a more detailed explanation of why you're doing (something). Part of the point of criminal law is for people to feel that justice is being done. That part is very important."

While prosecutors decide, defense attorneys must begin a mitigation investigation, just like they did under the old law. But if months later, prosecutors announce they won't seek the death penalty, defense attorneys have already spent thousands of hours and dollars for a case that won't need it.

Buhman said it's possible that when he files a charge of aggravated murder he could also immediately notify defense attorneys that the death penalty is off the table.

That one decision could save the county and taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars, defense attorneys say.

"It achieves the same goals that they want, if punishment is the issue, of taking someone out of society," said Rich Mauro, a contracted death-penalty case attorney working on a capital case in Box Elder County. "Plus it saves millions and millions for the taxpayer."

However, prosecutors say the decision to seek death requires significant consideration beyond budgets.

"If we aren't going to seek the death penalty, would it maybe save some money by notifying the public defender's office earlier on? Possibly," Taylor said. "Are resources limited? Without a doubt. But I'm not quite sure our death penalty cases should always be dictated by the pocketbook."

Long-run capital costs

The defense tab doesn't end at pretrial mitigation.

The $75,000 Means was granted for each of his new capital cases is only enough to cover the mitigation investigation and initial investigation costs. If the case actually had to go to trial, Means said he would need even more money from the county and its taxpayers.

"Tom Means has done a wonderful job in keeping those costs down as much as he can," Commissioner Anderson said. "He gets the best people ... and he gets a deal on it... but even at a deal it's expensive."

2 phases

Capital cases are longer and more expensive because there are two trials — a guilt phase and a sentencing phase. Expert witnesses, death-certified juries and numerous pretrial hearings and motions also add to the costs.

Death-certified juries mean that each juror must be willing to impose the death penalty if required.

"Local governments often bear the brunt of capital punishment costs and are particularly burdened," writes Richard C. Dieter, in a report addressing the cost of the death penalty published in 1992.

Dieter is the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, a nonprofit organization that studies capital punishment.

"A single death penalty trial can exhaust a county's resources," Dieter writes. "Politicians singing the praises of the death penalty rarely address the question of whether a government's resources might be more effectively put to use in other methods of fighting crime."

Since 2001, the Utah County Commission has allocated an extra $455,000 for capital homicide cases, and that number doesn't include funding for the newest case, Gardea, or any additional funding for potential trials.

However, capital-case trial funding hasn't been needed since 1996, when Ron Lafferty had a retrial for the murder of his sister-in-law Brenda Wright Lafferty, 24, and her daughter, Erica Lafferty, 15 months, in their American Fork apartment.

IIn 1996, the Deseret News reported that the costs associated with Lafferty's second trial, including court costs, jury fees and investigative fees ,was nearly $400,000 — a cost absorbed by the county and eventually passed on to taxpayers.

And now, 12 years later, Lafferty is still on death row winding his way through the appeals process.

Lafferty and the eight other men on Utah's death row have been there an average of 17.89 years.

"The message to come from that is (that) appellate courts take a very close look at death penalty sentences," Means said. "The last two cases to have gone to trial — which, by the way, was before our office existed — required retrials. It's gotta be done correctly the first time."

Douglas Stewart Carter, another death-row inmate, has been through several appeal-based hearings in 4th District Court after being convicted in 1985 of murdering Eva Olesen, the aunt of a Provo police chief.

Utah has only executed six people. The last was Joseph Parsons in October 1999 at a cost of $45,000, according to information from the Department of Corrections.

Parsons was sentenced in February 1988 for fatally stabbing a man who had picked him up as a hitchhiker, then stealing his car and dumping his body in a trash bin.

After a federal appeal petition was denied, he chose not to pursue an appeal to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals. Had Parsons pursued it, he would most likely be in the same place as Lafferty and Carter.

All attorneys agree the appellate process after a conviction is necessary, but many believe it's become too long and ponderous, exorbitantly expensive and emotionally draining to victims hoping for closure.

"The only closure in a criminal context has got to come from within one's self," Hart said. "As long as a victim's family hangs on to the hope of execution, their lives are going to be in turmoil while this execution is pending."

Buhman said when they file an aggravated murder case, they talk with the victims' families about the potential of a lengthy process.

"We think about that a lot," Buhman said. "They want closure ... and there is an issue with capital cases under the current scheme, they're very hard to get closure. So it's definitely a factor."

Gary Olesen has been waiting 23 years to see justice for his mother, Eva. He's attended numerous hearings for Carter, only to be told there are new filings or more delays.

"I think it's absolutely ridiculous the way it's going," Olesen told the Deseret News. "My mother hasn't had any appeals at all. Carter's been through how many now? I don't know how many. He's had his time, his day in court. It's time to end."

Olesen knows that punishing Carter won't bring his mother back or ease the pain he feels when he thinks about her brutal murder, but he said he stands behind the death penalty.

"The way he killed my mother he deserves it," he said. "I don't like to see people dead, that's not what I'm trying to get at, but if anybody deserves it, he does."

E-mail: sisraelsen@desnews.com