For a man who drives two top-of-the-line Mercedes, owns three homes and serves as CEO of a Fortune 500 company, Lynn Blodgett seems an unlikely advocate for the homeless. But when your brother has died at your side and two other siblings have died young, the empathy for others' misfortunes is genuine and hard-earned. Acquaintances say he has a heart of gold, which is ironic because the heart that beats in his chest is so flawed.

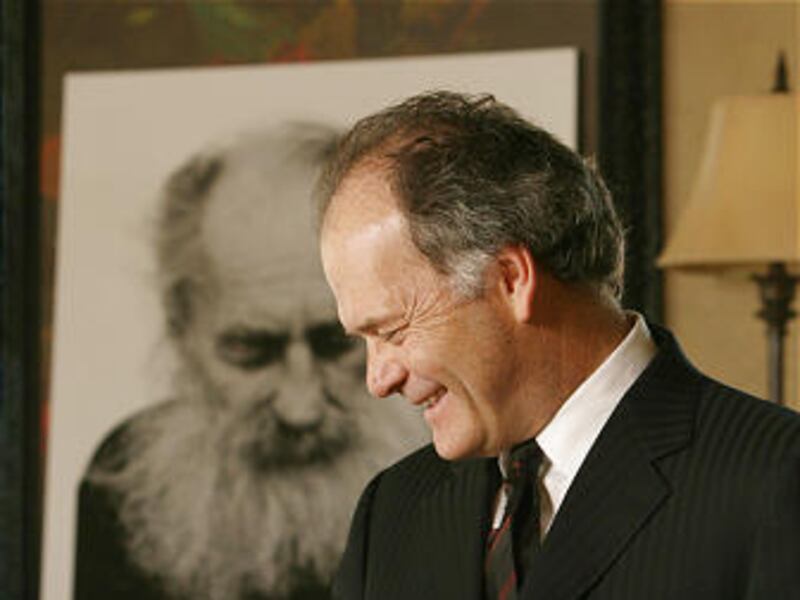

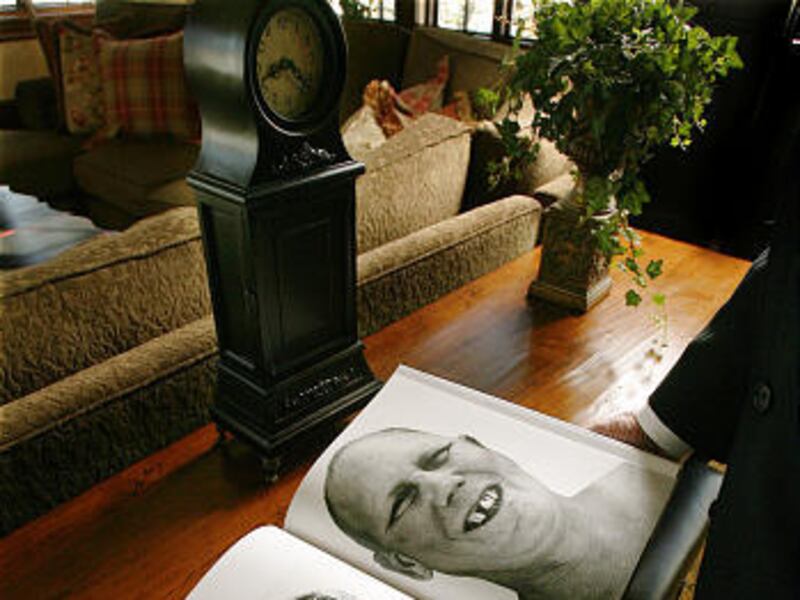

A tall, slender man with glasses and thinning black hair, he was a dedicated amateur photographer when he turned his lens on the homeless. After business meetings in cities around the country, he would remove his coat and tie, untuck his shirt and journey into the haunts of the homeless with a wad of $10 bills in his pocket and $30,000 worth of camera equipment on his shoulder. He did this for three years. The result: A 138-page book filled with his starkly beautiful black-and-white photos of America's homeless.

"Finding Grace / The Face of America's Homeless" has sold 10,000 copies and won critical acclaim (American Photo included it on its list of the top 10 photo books of 2007).

"I was just glad when we found a publisher," says Blodgett. "Now it's become a brand."

The book has become, if not the impetus, then the face of major fundraising efforts. "Finding Grace" was co-opted by United Way of Greater Los Angeles earlier this year for its HomeWalk event, which raised $1 million in a single day for the homeless. Prints from the book were plastered on the sides of buses and along the walk route.

The book was part of two homeless fundraising events in New York City that included an auction of Blodgett's prints at Sotheby's. The book was used in another fundraising event in Boston, with the prints being a stage backdrop for a concert that featured Bruce Springsteen, Natalie Merchant, Bonnie Raitt and Jon Bon Jovi (who has one of Blodgett's prints hanging in his recording studio). The book was also used by an event in Dallas to raise funds for a homeless shelter. More fundraising events are being planned that will continue to use the book as a marketing tool.

"These organizations have turned it into something meaningful, to raise funds," says Blodgett. "It was more than I ever expected. Now I think there's a lot more we can do."

Blodgett donates proceeds from the book to the Finding Grace Initiative, an organization created to assist the homeless. So far, the combined sales of the book and donations have raised $6 million.

"I think what the book does is give a face to something that tends to be faceless," says Blodgett. "The homeless are children, they're men and women, they're people."

The images of "Finding Grace" are visual poetry, haunting, yet warm glimpses of people living in the cracks and on the periphery of society. Thumbing through the pages of the book recently, Blodgett noted, in a hushed, reverent voice, "You cannot look away from their eyes."

In his day job, Blodgett is CEO, president and director of Affiliated Computer Services Inc., a Dallas-based $6.5 billion company with 600 worldwide locations that provides information technology and outsourcing services to private businesses and government agencies. In his free time, Blodgett, the divorced father of eight children, is a renaissance man. He's a master falconer who keeps his birds in their own air-conditioned house in his backyard; an avid reader of poetry and literature who can recite Emily Dickinson from memory; a connoisseur of music, with a weakness for everything from Eric Clapton to Etta James; and now a master photographer.

Born and reared in Salt Lake City, he attended BYU after graduating from Olympus High School. He lasted one semester before dropping out to go to work full time in the burgeoning computer industry. His parents, Jack and Joanne, had dived headlong into that industry in the '60s, well ahead of their time, working for a company based in Boston, which was Silicon Valley in those days. The Blodgett children joined their parents in the business at a young age, making frequent trips to Boston, where they learned about computers "right there in the laboratories," says Blodgett. Many of them pursued successful computer business ventures into adulthood.

Blodgett took up photography at 10 and bought his first falcon a year later. As he began flying his birds, his interest in photography soared too — he wanted to take pictures of the birds in flight. After returning from an LDS Church mission, he jumped into work and forgot his hobbies for several years until one of his peers told him, "One of these days you're going to be dead and you will have missed out on the things you love to do."

He took up photography and falconry again. He developed a passion for portraits while photographing his children. A few years ago, he applied for an advanced photography class at the Santa Fe Photographic Workshop under the direction of world-famous photographer Andrew Eccles, who has photographed hundreds of movie stars, models, athletes and musicians. To his surprise, Blodgett was accepted into the class — the only non-professional to make the cut.

"What do you want to get out of this?" Eccles asked him. Blodgett replied, "I would just hope that someday somebody like you would think that some of my pictures are good. Not great, but at least good." The exchange would prove to be ironic.

As Eccles notes in his introduction to "Finding Grace", he pegged Blodgett as a successful businessman with time and money to pursue photography as a pastime and didn't see much promise in his work. But after Blodgett turned in his first assignment, he writes, "I was forced to reconsider my first impression … he had captured some of the most compelling portraits I had ever seen taken by a workshop participant."

In the ensuing months, Blodgett sought further critique, at one point showing his prints to a Madison Avenue exec who had worked with legendary photographers. "Not bad," he said, "for an amateur."

Blodgett was crushed. "I finally told myself I've just got to get better," he recalls. He contacted Eccles' agent and asked if he could hire the photographer to teach him privately. It was tantamount to asking Joe Montana for private football lessons. Eccles eventually agreed to work with Blodgett for an hourly rate. Blodgett flew to New York monthly for three years to meet with him.

Eccles was brutally candid in their early meetings. Sorting through a stack of Blodgett's photos he would toss them one by one into stacks on his desk according to his evaluations — "Crap (toss the photo), crap (toss the photo), crap, crap, pretty good, crap, crap, crap." Then Eccles would review the photos again to offer specific critique on lighting, framing, angles, composition and so forth.

"I knew the camera, and I understood light, but to get a photograph at Eccles' level is different," says Blodgett. "Sometimes I couldn't even see what he was talking about."

By this time Blodgett was trying to wed two of his passions by producing 100 photos to go with 100 of his favorite poems. He eventually e-mailed a couple of shots he took of the homeless in Salt Lake City to Eccles. Eccles' reply: "These are great."

Says Blodgett, "It was the first time Eccles had ever put one of my photos in the 'great' pile."

Shots of the homeless are almost as irresistible to photographers as sunsets, but there was nothing cliche about them. After viewing more of Blodgett's homeless prints during one of their New York meetings, Eccles told Blodgett, "You need to focus on the homeless shots. These are so good that this could change people's perception about the homeless. You should do a book."

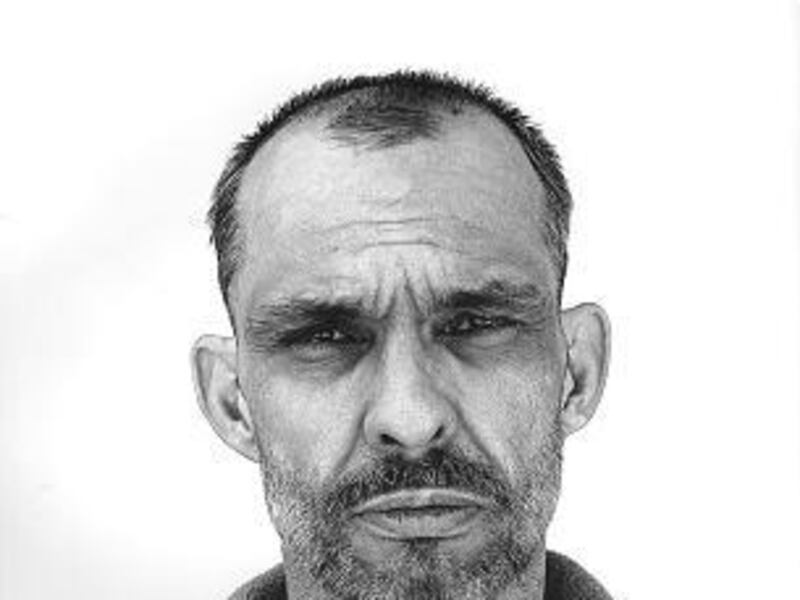

Blodgett established a routine during his frequent business travels. After meetings in Dallas, Santa Monica, San Francisco, Miami, Washington, D.C., he removed his business uniform and his jewelry to blend into the environment, armed himself with his cameras and a seamless roll of white paper and tape, which he used as background, collected $500 from an ATM, got it changed into $10 bills, and set out to find the homeless. He instructed his driver to let him out of the car several blocks from his destination and he walked to the shelter. When word spread about the man who was offering $10 to pose for photos, the subjects lined up. He taped his white background to walls, buildings, plastic bus stop shelters, even outhouses, and shot with available light. He coached his subjects to be natural.

"Typically, I would say, 'Tell me your story with your eyes,'" says Blodgett. "I don't care if you're angry, or if you think there is a God or isn't, or if you think the government screwed you, just tell me your story without words. If that didn't work, I'd say, 'Do you have kids?' These big, hardened, tattooed dudes who would scare you to death — I'd ask if they had kids, and they would think about it for a minute and all of a sudden, boom, there were tears."

Because many of the homeless wear several layers of clothing — it's easier than carrying a suitcase — Eccles advised Blodgett to ask his subjects to remove some of the layers, which revealed an assortment of scars, tattoos and scabs that told their own stories. He met a brother taking care of a brother contorted by disease, a sister duo, a dumpster diver, a cutter (people who cut themselves intentionally), a man who had been hopping trains for 18 years, a father living on the street with three small children. Looking at his photo of the latter, Blodgett says, "Those are not manufactured faces. You can just tell that the kid in this photo has seen things he should not have seen."

Blodgett was frequently moved to tears as he looked through the viewfinder. He especially remembers a woman he met in Berkeley, Calf. As he took his pictures, he asked her how she wound up homeless. As Blodgett recalls, "She said, 'I was in the bathtub and the Lord told me to get out of the tub and check on my little girl. I went to the front room and my boyfriend had a cord wrapped around her neck because she spilled his drink. I grabbed my little girl and ran out of the house.' The boyfriend was an executive for a large company. She was on the run. I'm shooting that, and it's overwhelming."

To find his subjects, Blodgett ventured into some of the seediest and most dangerous metropolitan areas in the country. He was never threatened even though it was obvious to everyone on the streets that he carried hundreds of dollars in his pocket. Only once was there trouble, and it occurred while he was taking pictures on a blistering hot day in Dallas. As usual, he had only enough money to photograph 50 people, and as he ran out of money he noticed there was still a long line of homeless waiting to have their picture taken.

He announced the crowd that he was going to go get water and money for them — he was finished taking photographs, but he wanted to give them the money anyway. By the time he returned, word had spread about a man handing out money and the line had grown to some 250 people. As Blodgett waded into the crowd handing out money and water, it turned into a mob scene; they swarmed him and grabbed at the money. As the situation began to spiral out of control and the money was going fast, Blodgett yelled to his driver, who was parked about 20 feet away, to get ready. He dashed to the car and sped off with the crowd in hot pursuit.

"It just showed the desperation these people have," says Blodgett.

Notwithstanding, Blodgett made a strong connection to these people who lived in another world from him, and it showed in his photos. "One guy recited a poem about crack cocaine as I was taking his photo, and my eyes were filling up with tears as I'm trying to look through the viewfinder," recalls Blodgett. "I said to him, 'I'll bet you've seen a lot of heartache because of cocaine,' and this big guy gets these tears. I put my arm around him and said, 'I'm sorry to put you through that.'"

Lauri Kratochvil, the redoubtable long-time photo editor for Rolling Stone Magazine, gushed when she saw Blodgett's prints in Eccles's office. Eccles explained that they weren't his photos and told her about Blodgett's project. Kratochvil immediately said she would like to edit his book. She accompanied Blodgett on one of his photo expeditions in San Francisco.

"You are able to establish a rapport with these people almost instantly," she told him. One lady approached Kratochvil and pointed at Blodgett, saying, "He's an angel, isn't he." Another observer from a CBS film crew told him, "These people listen to you and follow you."

Blodgett says the connection he made with the homeless was partly because he simply gave them the attention they need and crave.

"No matter what the issue, they're still human, and we tend to dehumanize them because we've walked by them so much," says Blodgett "You know the one comment I got from homeless people — the thing they say is the most painful aspect of being homeless — people don't want to acknowledge them. They won't look at the homeless. Think how that feels. I looked them in the eye and took time with them. It was their minute to tell their story. They were acknowledged."

Blodgett, whose innate warmth and kindness are apparent immediately to anyone who meets him, learned empathy at an early age. He and his eight siblings inherited heart arrhythmias and other health problems from both parents — a DNA double whammy.

When he was 10, Blodgett was baby-sitting his 4-month-old sister Nancy when her heart stopped. She was revived, but died at 13 of cardiac arrest. He was at his brother Jimmy's side in the hospital when he died at the age of 44 from diabetes complications. "I was helping him get more comfortable in his bed because his leg hurt, and he said, 'You're a good guy,' and then he died," says Blodgett. "He was my best friend."

His older brother Jack suffered a sudden cardiac arrest at 55 while washing his car. Blodgett rode in the ambulance with him, but his brother never awoke from a coma and died two weeks later.

Doctors installed a pacemaker and a defibrillator in Blodgett's chest when he was 35. Now 54, he can walk for exercise, but running takes its toll. One morning he was late for a plane at Salt Lake International and began running on the moving sidewalk while carrying bags.

"Then, wham, I was on my back," he recalls. "It took me a moment to realize what happened: I had been shocked by the defibrillator."

His mother and another brother, Tom, also have defibrillators, and his father and all of his other surviving siblings have health challenges.

"It's certainly had an impact on me," he says. "I can't be glib about people's misfortunes. My parents tried to teach us to be compassionate and understanding of people. I've always had a lot of faith. I think that I have been driven by a sense that things are pretty temporary.

"One thing that doesn't seem to change was made clear by Christ when he said, 'The poor you have always with you.' Wherever I travel — Paris, Washington, India, China — I find poor people. People holding a dirty paper cup in hopes of a coin, people shivering against the cold with little hope of escape, people who have lost most of what at one time identified them as an individual. I can't walk by them anymore without at least acknowledging them and feeling pain and a sense of my own unworthiness and good fortune."

He was driving in Salt Lake City one day when he saw Matt, one of the homeless men whose photo appears in "Finding Grace." Blodgett pulled over and approached him. Matt remembered the photographer. "My dad owns this place," he said, pointing to an adjacent business. Blodgett asked him, "How can I help you?" With resignation in his voice, Matt replied, "No, there's nothing you can do, but thank you, Lynn."

As for Blodgett, he has found his cause and his voice. When he submitted the photo that would eventually grace the cover of "Finding Grace," Eccles wrote to Blodgett, "You have graduated with honors."

In his introduction to the book, Eccles noted, "The photos in "Finding Grace" confirm my original love for photography as they remind me of its power. Lynn is a remarkable man, and he has become a remarkable photographer. I am proud to have played a part in bringing his insightful and sensitive vision to you."

E-MAIL:drob@desnews.com