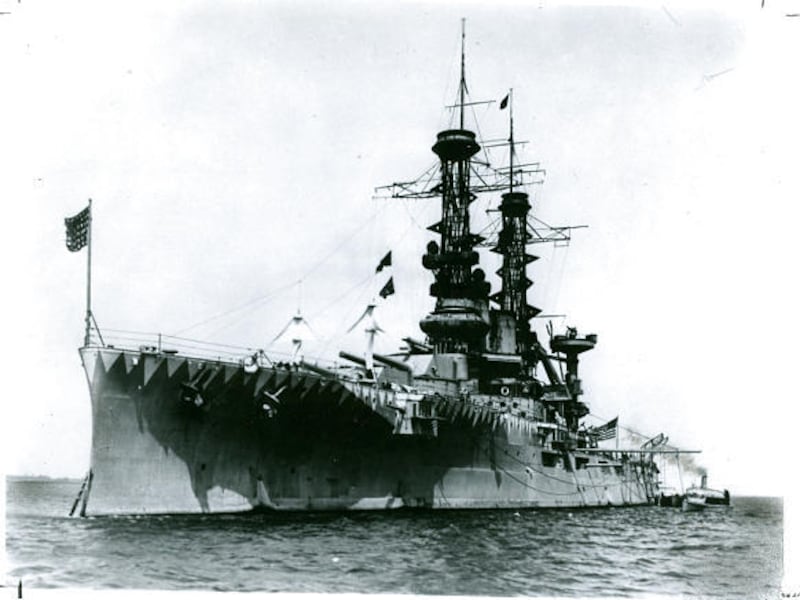

One hundred years ago she was the belle of Utah's ball, the largest and most powerful battleship in the world, launched in New York on Dec. 23, 1909 with these words: "I christen thee Utah! Godspeed!"

Thirty-two years later on Dec. 7, two torpedoes struck the USS Utah at Pearl Harbor and within minutes she rolled over on her side, taking some of her crew to rest with her forever.

As the decades passed, a solemn tribute to the horrific nature of the attack and the sacrifices of that infamous day was erected over the tomb of the USS Arizona, which would become the Pearl Harbor National Monument.

But on the opposite side of Ford Island rests the rusted hull of the USS Utah, which over the years has been termed "The Forgotten Ship."

Four men who have lived a total of 349 years on Earth ventured to the state of Utah earlier this year to remember what many have forgotten.

In the halls of the state Capitol, where an exhibit celebrates the life and times of the USS Utah, they talked of how good it was to see each other again, and how few they have become.

The four are among 30 or so men left from the 461 survivors of the assault on the 21,825-ton ship.

They felt her shudder from the torpedoes and watched tables, chairs, salt shakers and sugar bowls slide across the floor when she began to list.

"And it was one hell of a day, a terrible day," said Cecil Calavan, now 85.

Calavan was a 17-year-old farm boy in 1941 practically living on his own because of a family split. He talked his father into letting him sign up for the Navy, which had started recruiting 17-year-olds a year earlier.

He had grand visions of serving aboard a glorious battleship.

"When I first saw the Utah, I almost cried," he said. "She'd been cut back, she didn't look like a battleship anymore."

By the time Calavan came along, those glory days as a battleship were behind the USS Utah, which had seen action off the coast of Mexico in 1914 and was assigned to Bantry Bay, Ireland, to protect British interests at the beginning of World War I.

When Calavan came along, it had been a few years since the ship was selected to take President-elect Herbert Hoover and his wife on an extended tour of South America.

In 1941 when Calavan stepped aboard, the USS Utah had already spent the last decade as training and target ship for new bombers, barely reminiscent of her fighting past.

After only a couple of months on the Utah, Calavan changed his mind about her.

"I knew before she went down she was a great ship."

At the time of Pearl Harbor, Calavan was a seaman 2nd class, making $36 a month.

He was shaving with his Schick Injector — the newest thing on the market in 1941 — when he heard a plane come screaming in.

"It was a tremendous roar. I had heard planes overhead before, but nothing screaming like this. Within two minutes, the ship shuddered."

He looked out the porthole, and the next torpedo hit.

"I still could not believe it was an attack. We could see what we called the 'flaming hemorrhoids' on the planes and I knew."

? ? ?

By then, the USS Utah was in chaos. Seaman 2nd Class Robert Ruffato, now 86, said the men in the engine room were scrambling up to get out, and the men topside were trying to get below to escape the strafing by Japanese aircraft.

As the Utah began to list, Ruffato and a buddy rushed to the forward part of the ship, and dodging sliding furniture, jumped into the harbor.

The water was being riddled with machine gun fire.

"I'd go about 10 or 12 feet down, hang onto the corral and you could hear the bullets hitting the water, they were hot and sizzling."

Ruffato held his breath as long as he could, swam up, took a deep breath and went back down.

It was only 50 yards from the shore, but Ruffato said three 18-year-olds who didn't know how to swim were killed as they struggled in the water.

? ? ?

Scratched up and bleeding after sliding down the barnacles on the Utah, Warren "Red" Upton found himself bobbing in the water next to his lieutenant, who was clad only in his pajamas.

"He hollered at me, 'Can you swim, Red?'"

Upton, now 90, helped the officer over to the pilings and a motor launch ferried them to the dock, where the men took cover in a ditch.

"We were there for quite a few minutes, got to see quite a bit of the action," he said. "It was like a kaleidoscope of events is the way it impressed me, changing from one thing to another so rapidly. Naturally, you're trying to save your skin."

There in the ditch, he was just beginning to absorb the violent shaking of the Utah, of ducking ricochetting bullets as he scrambled up the starboard ladders. That night, he'd bunk with a bunch of other stranded sailors on the USS Argonne, using a gas mask as a pillow.

It was only a few days later, bandaged and lying in a hospital bed, that the enormity of what happened settled in for Clark Simmons, now 88.

A 20-year-old officer's steward from Brooklyn, Simmons had been on the Utah for a little over two years at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack.

"The Japanese were kicking our butts. It was something that we were not trained to do. We weren't trained for attack. We weren't at war."

Hit by a piece of shrapnel, Simmons impatiently convalesced in a hospital bed, listening to a replay of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's speech to the nation.

"It was at that time I realized how significant and serious the attack was. Some of the fellows visited the hospital, told me exactly what happened, the people who had been killed. It was really frightening."

It seemed like a lifetime ago that Simmons had ventured to shore — or the beach as the men called it — on the night preceding the attack to shop for papaya and pineapple. In the days to follow he and the others would find homes on new ships.

"If you lived through that attack, everybody had to fight now. The war was on," Calavan said. "Over the years, even nice men will fight."

Accounts differ, but the most widely agreed on number is 58 — 58 men who never made it off the Utah and remain with her today. The USS Arizona, which erupted in a fiery explosion, took 1,177 of her crew and remains a permanent memorial to the attack. The USS Oklahoma lost 429 sailors and Marines, but two years later she was righted and the bodies were recovered for burial. While being towed to California to be used as scrap, the Oklahoma sank at sea, leaving the Arizona and the Utah as the only ships at Pearl Harbor to remain at their berth.

It took 31 years, but a memorial was finally dedicated for the USS Utah, about a mile from the Arizona.

The surviving Utah crew figure that the horrific number of lives lost on the Arizona, coupled with limited public access to the Utah, has made it all too easy over the years for the dreadnought to earn the moniker of "The Forgotten Ship."

In 2008, however, one of the last things President George W. Bush did was sign an executive order transferring jurisdiction of the Utah from the U.S. Navy to the National Park Service.

The USS Utah Association anticipates that someday, the park service will provide transportation to visitors via shuttle to see the Utah.

There are some survivors, however, who reject the notion of ever having it duplicate the style of the Arizona memorial.

As one Utah survivor once told a friend, the Arizona is like a gorgeous, solemn church, and rightfully so.

"But everyone should have to see the Utah. It shows what war is actually like. The other shows what man can build."

e-mail: amyjoi@desnews.com