Joseph Tippets survived a plane crash in the Alaskan wilderness, struggling to stay alive for 29 days without communication from his wife or the outside world. He lost 50 pounds and constantly shivered from cold.

But through the whole ordeal, he never lost faith.

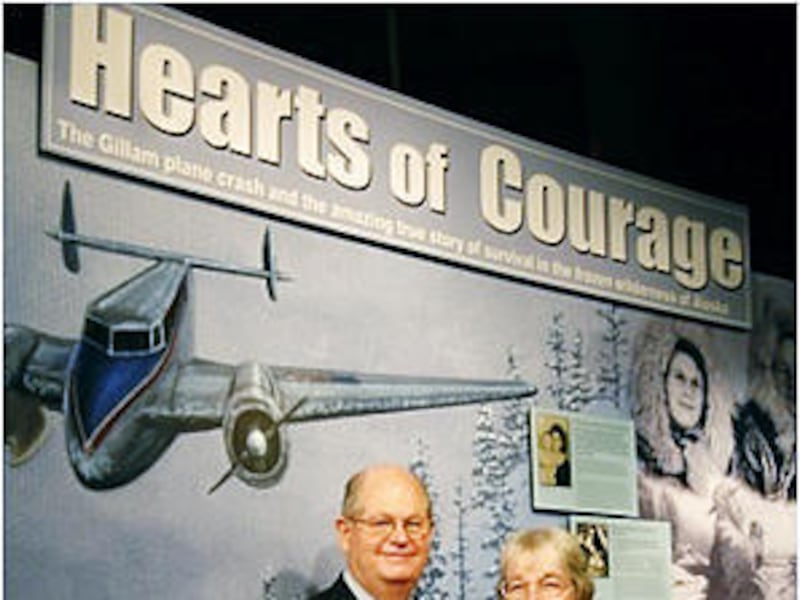

The harrowing and detailed story of Joseph Tippets' 1943 plane crash has been thoughtfully chronicled by his son, John Tippets, in his self-published book "Hearts of Courage," released in 2008. The account, replete with photographs and illustrations, began as a means of recording the story for posterity, but John decided it would be told best in book form.

"Doing it right just sort of became … terribly important," he said.

During the month Joseph and five other people aboard the small plane were missing, his wife, Alta, was left wondering about her husband's whereabouts and physical health but remained confident he was alive. Even when search efforts were called off, even when she received a letter from the First Presidency expressing condolences about her husband's likely demise, Alta remained firm in her belief that her husband of six years was alive and would come home.

Four of the six survived the month-long ordeal. Joseph was rescued Feb. 3, 1943, after he and another passenger left the crash site to find help. The pair were found malnourished and frostbitten, with supplies limited to a single sleeping bag they had shared, a .22-caliber rifle and the LDS scriptures Joseph insisted on carrying throughout the whole ordeal.

John's father died in 1969, and his mother died in 1973. He hired artists and a photographer to travel to the remote crash site and photograph the remains of the plane. The art all adds to the man-versus-nature tale, with photos of Joseph and his fellow passengers' rescues and hospital stays included. John researched scrapbooks and newspaper clippings and spoke with the descendants of a few of the other crash survivors while compiling the material.

John initially set out to write the book from his own perspective, but found he had plenty of original-source material, including direct quotes from his father, and changed his approach.

"I'm spending all this effort translating it into third person — that's silly," said John, who ended up writing from his father's point of view. "It's his story, let him tell the story.

"I felt really good about that decision ever since. … I really wanted him to have that credit."

Those first-person details add feeling to the book, like when Joseph calmly puts on his galoshes after one of the plane's engines goes out and all those on board become aware that they will inevitably crash.

John's wife, Bonnie, helped edit the book. She said they both have felt his parents' helping guidance while working on the story.

"One of the things that Bonnie and I have really felt is that this is really Mother and Dad's project," John said. "It's really like they're telling us how to do it now."

John, who was just a year old when his father's plane went down, said he heard his dad tell the story often when he was growing up, and thinks of the survival story the way others think of their pioneer heritage stories.

"He would tell it for father-and-son outings, for firesides and social gatherings, at church and sometimes away from church settings," John said. "Most of us have some pioneer ancestor stories that we love. Well, this is a little closer in but very similar."

At one point in the book, after he is rescued, Joseph contacts his childhood Scoutmaster to thank him for instilling some know-how of self-preservation when he was young. When recounting his story to youth leaders, Joseph would encourage them to keep teaching the lessons, because even though they might not seem to care, "kids are hearing and someday they may really, really appreciate what they learned."