There's a child in the kitchen doing homework, there's a child at the piano pounding out scales and there are children in the backyard, squealing as they jump together on the trampoline. But still, Gary Ceran's home feels empty.

Where now there are five children, last week there were eight.

"I just don't feel like my family is complete," Ceran said.

He thought, two weeks ago when he invited three Ukranian orphans into his home through the Utah-based nonprofit Save a Child, that he was giving them the chance of a lifetime — the opportunity to have a two-week "American experience." Instead, he discovered, "the rest of my family." Now the little blondes, Christina, 11, Sasha, 9, and Eddy, 8, have gone back to Europe, and Ceran, who hopes to adopt the orphans, is left with nothing to do but pack up their clothes and wait to be reunited.

It is a familiar feeling. Waiting. Aching.

Ceran, who has always dreamed of having a big family, has spent the greater part of his adult life trying to fill up his home with children.

At first, he waited for, ached for a healthy baby. His first two children — a set of twins — were born prematurely and died shortly after birth. He lost three more to brain cancer. Ceran and his wife Cheryl kept praying, though, and eventually they brought home four strong babies. Then, Christmas Eve 2006, a drunken driver plowed into the family car and killed Cheryl and two of their children. Ceran discovered, at that time, a different kind of waiting — one that he will have to endure until his death, when he believes his family will be reunited in heaven.

"All of a sudden, your house is very quiet," he said. "People with kids long for quiet houses. That's foolishness, in my opinion. Children's laughter is like music to me."

Though Ceran added four stepchildren to his family when he married his now-wife Corrine, he said the two wanted to have a baby together to "unite" the family. When things didn't work out naturally, they dived into the world of fertility treatments and began, again, the process of waiting, aching.

"Ukrainian orphans," Ceran said, "are not exactly what I had in mind."

When his wife suggested last year that the couple sign up to host a few orphans, he thought, "Why not? That would be fun." But as for adopting, there are easier ways, Ceran said — ways that don't cost $40,000, include overcoming a language barrier or dealing with the psychological problems that come from abuse and neglect.

Corrine Ceran, though, was haunted, after reading a Deseret News article about the Save a Child program, by the idea of a child growing up in a cold, unfriendly institution. In Ukraine, the orphanages kick the children out when they turn 16. Without a family to rely on, 90 percent turn to drugs and prostitution. Save a Child brings orphans between the ages of 6 and 15 to the United States for a two-week vacation where they take them swimming, horseback riding and give them the opportunity to experience, for a moment, what it's like to be part of an American family. Though the children must return after their two-week stay, Vern Garrett, the program's president, said the ultimate goal is to find the children a home. In the past five years, Save a Child has matched up 100 Ukrainian orphans with new, American parents.

"When I read that article, I remembered being 10, sitting in my room, praying for, longing for a dad," said Corrine Ceran, whose father abandoned the family when she was young. She cut out the article and put it in her journal. She wasn't yet sure, though, that Christina, Sasha and Eddy were meant to be hers.

For her — and for Gary Ceran — that realization came later.

It came after the family met the trio at the Salt Lake City International Airport, when they stood, awkwardly at first, unsure how to communicate with one another.

It came after the couple taught the children about Halloween and took them trick-or-treating for the first time. When the Cerans typed the words "trick-or-treat" into an online English-Ukrainian translator, Christina started acting strange. The dictionary interpreted the harmless holiday phrase as, "Your wallet or your life." In the end, they had to pantomime. Eddy was so excited he ran straight to the neighbors (at 10 p.m. on Oct. 30) and started ringing doorbells.

It came after Corrine Ceran took the children, who were limping around in too-small shoes, to the store to do some shopping, after she taught Christina how to bake cookies, after Sasha threw a fit and refused to eat anything but potatoes and toast, and after the family gave the orphans their first lesson about Jesus.

"I stood up to bear my testimony of God's love, and I knew," Corrine Ceran said. "I knew that if these children — if they chose — were meant to be a part of my family."

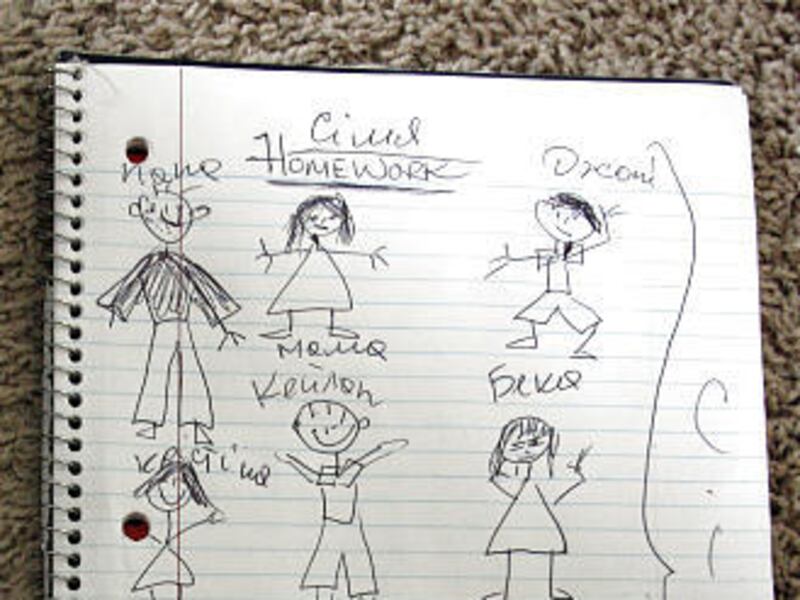

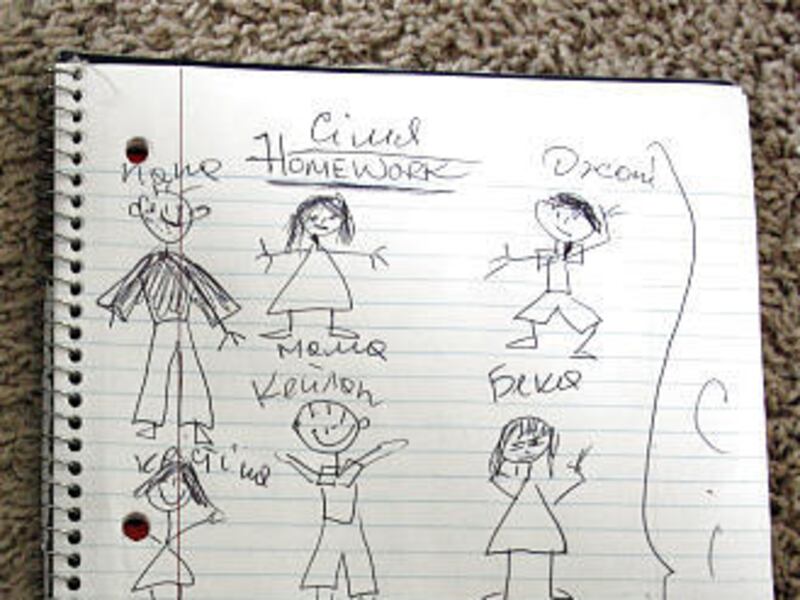

She had asked the children earlier in the week, between Uno games and trips out back to, as Eddy called it, "go boing boing" on the trampoline, what they thought about coming to America to live. Eddy and Sasha gave her two enthusiastic thumbs up. Christina, who had been a mother to her two brothers for as long as she could remember, responded with a conflicted frown and a thumb set parallel to the ground — the signal the family had designated to mean "maybe."

After Corrine Ceran shared her thoughts in church that day, though, Christina took her aside. "Yes Ma Ma. Yes Pa Pa. Yes America," she said.

At that point, everything was clear. Jonny, the Cerans' 11-year-old, put it this way, "When they came, our family felt complete." Gary Ceran, overcome with emotion, could only nod.

e-mail: estuart@desnews.com