CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Elder Dallin H. Oaks urged Harvard students on Friday to take more than a superficial approach to religion, an approach he said is exacerbated by the secular American university system.

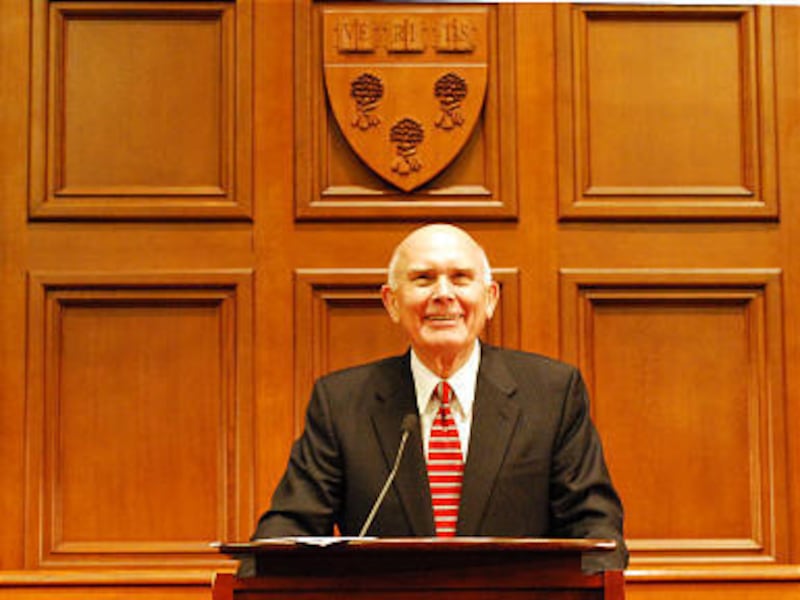

Noting that speaking to such a diverse audience is a challenge, Elder Oaks, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, said, "My object is to illuminate several premises and ways of thinking that are at the root of some misunderstandings about our doctrine and practice."

Elder Oaks acknowledged that LDS doctrines and values are not widely understood by those not of the LDS faith, and said that his disappointment with that "is only slightly reduced" by research that shows "that on the subject of religion Americans in general are 'deeply religious' but 'profoundly ignorant.'"

Elder Oaks was introduced by Harvard law professor Mary Ann Glendon, the faculty adviser for the LDS student group (Harvard Law School does not have an LDS professor). Glendon is a devout Catholic and former U.S. ambassador to the Vatican.

Elder Oaks said the higher education system was partly to blame for prevailing ignorance about many aspects of Christianity and other religions.

"Many factors contribute to our people's predominant shallowness on the subject of religion, but one of them is surely higher education's general hostility or indifference to religion," he said. "Despite most colleges' and universities' founding purpose to produce clergymen and to educate in the truths taught in their chapels, most have now abandoned their role of teaching religion.

"With but few exceptions, colleges and universities have become value-free places where attitudes toward religion are neutral at best. Some faculty and administrators are powerful contributors to the forces that are driving religion to the margins of American society. Students and other religious people who believe in the living reality of God and moral absolutes are being marginalized."

"(I)t seems unrealistic to expect higher education as a whole to resume a major role in teaching moral values," Elder Oaks said. "The academy can pretend to neutrality on questions of right and wrong, but society cannot survive on such neutrality."

Elder Oaks said he chose "three clusters of truths to present as fundamental premises of the faith of Latter-day Saints." Those clusters are:

The nature of God, including the role of the three members of the Godhead, and the corollary truth that there are moral absolutes.

The purpose of life.

The three-fold sources of truth about man and the universe: science, the scriptures and continuing revelation, and how we can know them.

"Our theology begins with the assurance that we lived as spirits before we came to this earth," he said. "It affirms that this mortal life has a purpose. And it teaches that our highest aspiration is to become like our Heavenly Parents, which will empower us to perpetuate our family relationships throughout eternity.

"We affirm that marriage is necessary for the accomplishment of God's plan, to provide the approved setting for mortal birth and to prepare family members for eternal life.

"There are many political, legal and social pressures for changes that de-emphasize the importance or change the definition of marriage, confuse gender or homogenize the differences between men and women that are essential to accomplish God's great plan of happiness. Our eternal perspective sets us against such changes."

Elder Oaks also explained why personal revelation is such a fundamental premise to Mormons.

"Some wonder how members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints accept a modern prophet's teachings to guide their personal lives, something that is unusual in most religious traditions," he said. "Our answer to the charge that Latter-day Saints follow their leaders out of 'blind obedience' is this same personal revelation. We respect our leaders and presume inspiration in their leadership of the church and in their teachings. But we are all privileged and encouraged to confirm their teachings by prayerfully seeking and receiving revelatory confirmation directly from God."

Elder Oaks' visit to Harvard, his first on the campus, was organized by Benjamin Geslison, president of the Harvard Law School Latter-day Saint Students Organization.

"It's difficult to overstate the value of this opportunity to hear Elder Oaks speak and to ask questions about the Mormon faith from one who can speak on behalf of the church and not just as a member of the faith," Geslison said.

Geslison said the speech and Q&A was being recorded by the LDS Church and would likely be broadcast in between sessions of general conference. After speaking for about 45 minutes, Elder Oaks answered questions on everything from homosexuality and Proposition 8 in California to personal revelation and the nature of adoptive families.

Elder Oaks was a law clerk to Chief Justice Earl Warren and worked as a professor at the University of Chicago Law School. He served nine years as president of Brigham Young University and was a justice on the Utah Supreme Court. He resigned from the court before his ordination in 1984 as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

Ben DeVan, a student at the Harvard Divinity School, asked Elder Oaks what made Mormon revelation different from revelation received by Muslim founder Muhammad and Mary Baker Eddy, founder of the Christian Science movement.

"Why should we believe that what Joseph Smith said is true as opposed to these others?" said DeVan, a Christian from Atlanta.

"If you want to know, go to the ultimate source," Oaks replied. "The answer to that question can only come from God himself. That's what I encourage anyone who asks me about it. ... I can't promise when it will happen with anyone, but I can promise it will happen."

When asked by another student from Harvard Divinity School whether Mormons considered themselves to be evangelical Christians, Elder Oaks demurred.

"In many organizational things that they do, we are not identified, and so it's a hard question to answer," Oaks said. "We sympathize with some things, but if a person were describing the religious landscape, I don't think we'd want to be listed in the religious landscape as evangelical Christianity. ... And from what I read about some of the pronouncements from some of their leaders, I think that feeling would be mutual."

The 300-seat room inside the Ames Courtroom at Austin Hall was filled to capacity. The audience was made up largely of students at Harvard Divinity School and Harvard Law School.

For five years running, the Harvard Law LDS student organization has brought in a prominent LDS lawyer or academic to address the Harvard community as part of its Mormonism 101 Series.

"I'm not a Mormon, however, I feel that today's event was very enlightening. ... I found a lot of the things that Dr. Oaks spoke about to be interesting," said Michael De'Shazer, 21, a graduate student studying computer science student at Harvard Extension School. "For Mormonism 101, it was pretty good."

Two years ago the series featured Elder Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School and an area seventy.

Last year's keynote speaker was Tom Griffith, a federal judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

"Kudos to the organizers and to those who attended for creating a forum in which people of good will could talk civilly to one another about important matters," Griffith told the Deseret News. "Preparing my remarks forced me to think through the best way to explain who we are in a relatively short period of time to a remarkable group of people who knew something about Latter-day Saints but wanted to learn something more."

To read a full text of the speech, click here.

e-mail: jaskar@desnews.com