SALT LAKE CITY — Each day for nearly 17 years, Debra Brown has woken up in a cement cell, clad in a nondescript, cotton jumpsuit. Sometimes it's hard to remember the date, with days blending into months and winters melting into springs — no fishing trips or family birthday parties to break the monotony of incarceration.

Though she never finished high school, Brown keeps her mind focused by reading, crocheting and writing letters, and today's letter is addressed to her older brother, Dave. As she finishes, she tucks in a picture of a shiny, blue bicycle torn from a magazine. Underneath it, she had scrawled the words, "No way this will ever happen."

It's a rare twinge of pessimism from a woman who has survived nearly two decades in prison for a murder she insists she didn't commit.

Yet after years of nothing but faith, Brown now has a chance to prove her innocence under a new Utah statute.

Her attorneys insist it's only a matter of time before the state must rectify the mistakes that put an innocent woman behind bars. Yet, it's also possible that Brown's evidence isn't the "clear and convincing" proof the new law requires.

Brown, 53, is just one of thousands of inmates across the country who insist they have been wrongfully convicted. She's part of a national movement that's been growing since 1989, when the first DNA exoneration took place. Since then, 266 people have used post-conviction DNA testing to win their freedom in 34 states. In Texas alone, 41 people have been exonerated through DNA evidence.

The Rocky Mountain Innocence Center, a non-profit, Salt Lake City-based organization, is one of nearly 75 "innocence centers" across the country working to free the wrongly accused. In most cases, innocence centers are staffed by a combination of volunteer attorneys, law school professors and law students.

Every year, the RMIC receives nearly 200 letters from inmates in Utah, Wyoming and Nevada who want their cases reviewed. After an intense screening process, the RMIC chooses only two or three a year to investigate. Since they started in 2000, the group has taken fewer than 20 cases to court, though they've investigated dozens more. If Brown is released she will become only the second person in Utah history to prove she was wrongfully convicted.

"We are not wasting time and resources," said Katie Monroe, executive director of the Rocky Mountain Innocence Center. "We have confidence in the cases we look at and bring, and the idea that there's some kind of flood of appeals by people in prison that we are bringing would be a myth."

Brown has no DNA evidence to rely on, but the Rocky Mountain Innocence Center chose to pursue her innocence claim because they believe her story is compelling enough without DNA. Despite the strength of DNA evidence, experts estimate it's only available in roughly 5 to 10 percent of cases.

Over the last nine years, the RMIC has been uncovering and piecing together new bits of evidence that they believe would have resulted in a very different trial outcome for Brown.

Although 11 cases requesting exoneration are pending before the state, Brown's is the first claim under Utah's new "factual innocence" law to be heard by a judge, and a good case to illustrate why innocence projects do what they do, Monroe said.

"We all lose when the wrong person goes to prison," she said. "It's a public safety issue, public resource issue, confidence in our criminal justice system issue. We know that the work we do serves the entire community, not just people who are innocent in prison."

Thanks to that work, Brown's family has begun preparing for the day she comes home. Brother, Dave Scott, found the longed-for shiny blue bike Brown asked for years ago in a letter. It's waiting in his shed.

"Those of us who are committed to this just ... ache for people who are wrongfully imprisoned," Monroe said. "What keeps us going ... is someone like Deb Brown, who is one of the most gentle, selfless and strongest people I've ever met. In a case like that ... it's the person in prison who gives us that strength and seals that commitment."

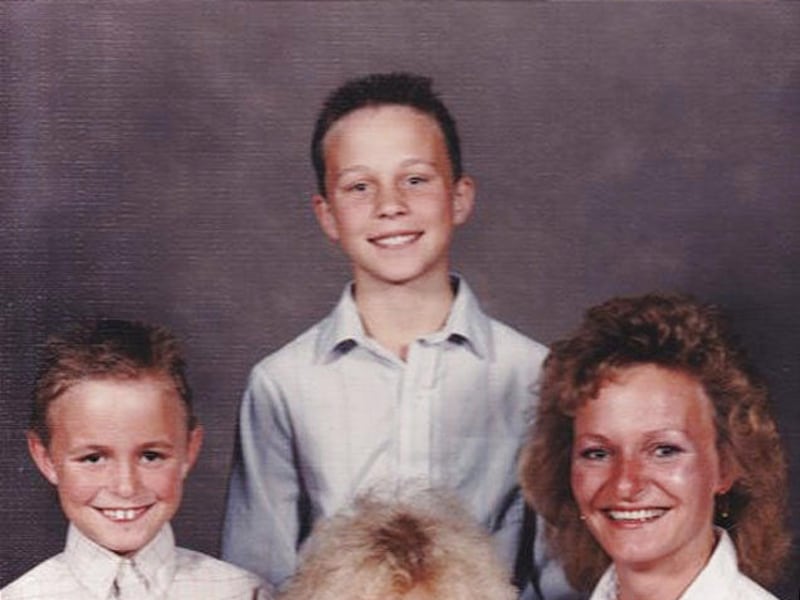

Debra Brown

"The best way to describe (my mom) is just a strong lady," said Ryan Buttars, Brown's oldest son, now 35. "She wasn't like your typical mom who's at home baking cookies. She was the mom that if you came home and talked back she'd put you in your place."

Born December 17, 1957 in Logan, Brown grew up in a dysfunctional family of four. Her parents couldn't control their finances and fought constantly, splitting when she was still a child. After that, her dad slipped out of her life. Yet Brown has always stayed close to her brother, Dave, who was just one year older.

School wasn't much of a priority for Brown, who married at 14 and had her husband, then her legal guardian, sign the papers allowing her to drop out of 9th grade. She began working as a carhop in Logan, eventually moving on to work at the nearby cheese factory.

By 18, she gave birth to a baby boy, and after a divorce and another marriage added two more children to the family. Her lifestyle became somewhat transient, with little permanence for her children. They bounced from rented homes in Montana to small apartments in Wyoming, Idaho, Colorado and Utah.

In and out of relationships and without a high school diploma, Brown worked odd and often difficult jobs to keep her kids fed. She painted and roofed houses and mined coal. While Brown worked, Ryan, only a young teenager, kept the house clean and watched his younger siblings, Josh and Alana. They'd throw dinner together with a few cans of tomato soup and some dry bread for grilled-cheese sandwiches. Budgeting was never Brown's forte. As a 15-year-old, Ryan remembers days in Montana when he would loan his mom money from his first job at a Hardee's restaurant.

"We didn't really need a whole lot," Ryan said. "We grew up with nothing, but you could go back to any one of those days and visit us and we were the happiest kids ever. We created our own fun."

Despite her financial struggles, Brown worked hard to create a warm and loving environment at home, and she made sure her kids had fun. Her daughter Alana remembers going to the roller skating rink each Friday night as an 8-year-old and getting $20 to spend on candy. In the end, even if there were bills to pay, the persistent kids always won.

The most beloved memories though, were piling into their old Toyota pick-up and driving to Bear Lake, where they'd spend the day playing on the beach and fishing.

And while Brown's jobs were rarely steady, she worked hard and taught her kids to do the same.

"The biggest thing that we took from her is just to work hard at everything you do," Ryan said. "Whatever her job, she'd make sure she was good at it."

It was that work ethic that propelled Brown into the life of Lael Brown (no relation), an elderly, wealthy landlord with properties throughout Logan.

A quiet man with a dry sense of humor, Lael had a string of low-rent apartments, which he rented to the tenants others wouldn't.

Although he was wealthy, he didn't flaunt his money. His ex-wife and business partner, Clara, lived in a beautiful home, while Lael chose to live in one of his smallest and oldest units on 500 North. And rather than buying a new truck, he kept pouring money into his old, red-striped Centennial truck. He could have afforded better clothes too, but chose to wear his old, worn-out ones instead.

Yet most everyone knew that Lael carried large amounts of cash from collected rent payments, keeping that cash in his home, along with loaded guns near the front door, his bed, and in his bedroom closet.

The crime

After they met, Lael hired Brown to help with maintenance and property upkeep. Lael taught her how to plaster walls, fix broken windows and lay floor tiles, and would often fix her "nickel-and-dime" cars, which seemed perpetually on the verge of a break down.

Lael was also an avid fisherman, and he and Brown would often sneak away from work to fish, then follow it up with a slice of pie and a cup of coffee at Freeman's Café. Over their 10-year friendship, the coffee and pie became a daily tradition.

Each day Lael, 75, and Deb, 36, would head to either Angie's or Freeman's. They preferred the latter, which had better pie and they could smoke while they talked.

Despite an age difference of nearly 40 years, the two friends relied on each other for support — Lael for the strength and energy of a hard worker, and Brown for stability and father-like support.

On Friday, Nov. 5, 1993, Brown and Lael met at Freeman's Café like usual, but Lael didn't feel well and only ordered coffee. He left shortly after to go home and rest. Concerned, Brown fixed Lael a pot of chicken noodle soup, which she took to Lael's house that Saturday afternoon. When he didn't answer the door, she left the pot on the doorstep with a note, knowing it was cold enough the soup wouldn't spoil. Small acts of kindness were common for Brown, who family members say would "give you the shirt off her back" if you needed it.

When Lael failed to show up at Angie's Sunday morning for coffee, Brown's concern grew. She drove to his house, where she noticed the soup still on the porch.

When Lael again didn't answer the door, Brown used the key he had given her and went inside.

She called out. No answer. She walked into his bedroom.

There, she found Lael lying on his bed facing the wall, surrounded by a puddle of blood.

Brown ran outside screaming, trying to get someone's attention. Finding herself alone, she went back inside and dialed 911.

For nearly half an hour after officers arrived, they searched for a murder weapon, convinced Lael's death was a suicide, even moving the body before photographing it.

Failing to find a gun, they proceeded with a homicide investigation, gathering .22 caliber bullets, cigarette butts and a pair of pants from the floor. Lael's wallet, checkbook, all the cash he kept in his home and his .22 caliber Colt Woodsman pistol were never found.

Police noted the front storm door's glass was smashed, and the front door's lock was broken. The back door was held shut with a knife wedged in the door jam.

Officers found blood on Lael's nightstand, the refrigerator door handle and in the kitchen sink, where it looked like someone had washed their hands. They also found a bloody handprint on the door and "quite a bit" of blood on the floor.

Yet officers didn't photograph or preserve any of the blood evidence.

Narrowing in

As the investigation began, Brown felt like a member of the team, helping police follow-up on leads and tracking down details that might find her friend's killer. Interviewed twice the day of the murder, Brown also allowed police to search her truck, purse, home and clothes. They found no weapons, money or blood.

During the first of 20 interviews with Brown, the police seemed like friends, Brown's son Ryan remembers. Yet over the 10-month investigation, officers stopped coming to the house and instead asked Brown to come down to the police station. They no longer allowed Ryan to sit in on interviews, and their tone changed from friendly to accusatory.

Police questioned Brown about forged checks they had found in Lael's home made out to her for nearly $3,000, and wondered why other financial documents were missing from his home.

Brown told police she owed Lael money, but denied forging the checks. Throughout their friendship Lael had often loaned her money, no questions asked.

Police didn't believe Brown's denials and developed a working motive that Brown had killed her boss to cover her financial deceit.

(Years later Brown finally admitted she had written the checks, and was ashamed to have taken advantage of Lael's friendship. She had been terrified that admitting to forging the checks would somehow link her to the murder.)

Around Logan, the gossiping about the murder was becoming unbearable. Teachers pulled Brown's kids aside after school to ask how they were doing. Strangers stopped her on the street to talk about it. And when patrons at Angie's and Freeman's Café began discussing it over coffee, Brown stopped going. She moved to Idaho, leaving police with her number and address and coming down often to visit Ryan as well as Josh and Alana, who were living with their dad at the time.

Her last visit was September 9, 1994. Brown had just pulled into a motel parking lot and was unloading her suitcases when patrol cars screeched up beside her. Logan officers jumped out and immediately slapped handcuffs on her for the murder of Lael Brown. She reassured her children that everything would be fine; she had done nothing wrong. Her children believed her.

But once in custody, things slowly slipped downhill. Brown's public defenders — she couldn't afford her own attorney — met with her less than three times for a collective total of four hours. She never saw the police reports, never knew there was information about other potential suspects and never got a chance to take the stand in her own defense.

In October 1995, 12 jurors deliberated for six hours before unanimously finding Brown guilty of murder. She was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole.

A second chance

Each year in America, hundreds of thousands of people are arrested, tried, convicted and sent to prison. Yet each year, exoneration advocates know that thousands of them are there by mistake.

In a study — "Convicting the Innocent" — published in 2008, University of Michigan law professor Samuel Gross estimated the false conviction rate for capital murder convictions is 2.3 percent. For rape-murder cases the percentage range increased, 3.3 percent to 5 percent.

Extrapolating out to include all prison sentences, a 2.3 percent false conviction rate would mean that from 1977 to 2004, roughly 185,000 innocent defendants spent at least one year in prison, Gross wrote. And to innocence advocates like Katie Monroe, that's simply not acceptable.

"Those of us who work in this field just feel really strongly that innocent people shouldn't be in prison," Monroe said. "I also feel really strongly that the criminal justice system should work better."

To that end, she has dedicated her life to investigating the cases that have fallen through the cracks and placed potentially innocent people behind bars, as well as advocating change.

Monroe — an attorney who previously worked at the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and served on the board of the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project out east — knows personally just how quickly things can go wrong. Her own mother was wrongfully convicted for a murder she didn't commit.

In March 1992, Roger de la Burde was found dead on his Virginia couch with a bullet in his head and a gun in his hand. Soon after, his long-time companion and Monroe's mother, Beverly Monroe, was slapped with the charge of murder.

Monroe worked for seven years to find exculpatory evidence that prosecutors never shared with her mother's defense team. Thanks to her work, her mother was released from prison in June 2003.

Even though each case has a unique set of circumstances, those who investigate innocence cases point to several disturbing and reoccurring themes. In more than 75 percent of the country's 266 DNA exoneration cases, at least one eyewitness made a mistake. In almost 25 percent of these cases, defendants made incriminating statements, confessed or even pleaded guilty — most likely because of police coercion, threats or mental challenges. "Snitch" testimony is also an issue. In more than 15 percent of DNA exoneration cases, prisoners serving long sentences traded incriminating evidence regarding the accused in exchange for privileges or an early release.

"The (judicial) system is designed to ferret out the truth, but there's no system that you could create that would be 100-percent accurate," said Chris Martinez, one of Brown's new attorneys. "What's unique about Utah, and what I think is very admirable, is that they put this statute on the books that allows people a second chance."

That second chance is officially called a "petition for determination of factual innocence," which in 2008 was added to Utah's "Post-Conviction Remedies Act." The law allows inmates to bring newly discovered, exculpatory, non-DNA evidence into court.

If, after considering an inmate's claim, the judge finds them innocent, he or she can dismiss the case and also order the person's record expunged. Utah is only state in the country with such a law.

"The issue is 'What is innocence?'" asked Alan Sullivan, another of Brown's new attorneys. "Does it mean that we can prove (Brown) was somewhere else when the crime was committed ... that she has a perfect alibi? Or does innocence mean, in the context of a circumstantial evidence case, that each of the elements of the circumstantial evidence is now proven to be wrong?"

Sullivan believes they can do just that - disprove each of the former prosecution's key points with their new evidence.

Finding hope

For years, Brown's family believed she was innocent, but didn't know what to do about it. They had never heard of the Rocky Mountain Innocence Center, and until 2008 there was no "factual innocence" law.

"Even now, there's just this overwhelming guilt that we just gave up," Ryan said. "We didn't know what to do. I often wonder, had we kept with it, would we have been able to get her out sooner than now? And that's the thing that kills us. The Rocky Mountain Innocence Center took this case and built something so strong ... (when) we thought it was impossible to prove (her) innocence."

The RMIC became aware of Brown's case in 2002, when a former court clerk doing religious outreach through the Utah State Prison met Brown and became convinced she was innocent. The Center then contacted Brown in prison, and her explanation sparked the new, nine-year journey toward freedom.

"As we looked at this case, it was a purely circumstantial case," said Jensie Anderson, president of the Rocky Mountain Innocence Center, law professor at the University of Utah S. J. Quinney College of Law and Director of the Innocence Clinic there. "We began to realize quite early that the circumstances really weren't as clear cut as they had been presented at trial."

The jury heard testimony that at the time of the crime, Lael's house was securely locked, the windows painted shut and that only one person had a key — Brown.

Yet Brown's attorneys have since learned that Lael's son also had a key, and that Lael's grandson had burglarized the house more than once. They have also learned that police opened windows on the day of the murder and the back door may have been secured only with duct tape.

The medical examiner testified that the murder probably occurred Saturday morning between 6:30 a.m. and 10 a.m. — the only time that weekend that Brown didn't have an alibi. However, the RMIC has uncovered evidence that the medical examiner initially declared the time of death to be roughly midnight Saturday or early Sunday morning. They also have found evidence that suggests that the prosecutors and medical examiner conspired to change the time of death to put Brown at the scene of the crime.

Witnesses have since come forward to say that they saw Lael Saturday afternoon, eliminating the possibility that he was killed Saturday morning, Anderson said.

Brown's attorneys also believe that evidence about another potential suspect was never fully investigated. Bobbie Sheen was a tenant with a troubled past who had recently been evicted from one of Lael's apartments. Sheen had complained to a friend about Lael and his wealth, then mysteriously began flashing around large amounts of cash near the time of Lael's death. Sheen also had a gun almost identical to Lael's, which he refused to sell to his interested friend, instead disposing of it in the marina.

Brown told police about Bobbie Sheen's eviction and one of Sheen's friends tried to tell police about the angry comments and piles of money, but was told to stay out of it. Police may have known many of these important details, but the jury never heard them, Brown's attorneys say. Sheen committed suicide in August 2007.

Defending the past

Scott Reed, division chief of the Criminal Justice Division for the Utah Attorney General's Office, said the state doesn't believe they've seen any actual facts that could exonerate Brown.

"If she's claiming to be innocent, she ought to have every opportunity to prove that, but you've got to have evidence, proof," he said, "not just the systematic dismantling of the state's prosecution from 15 years ago."

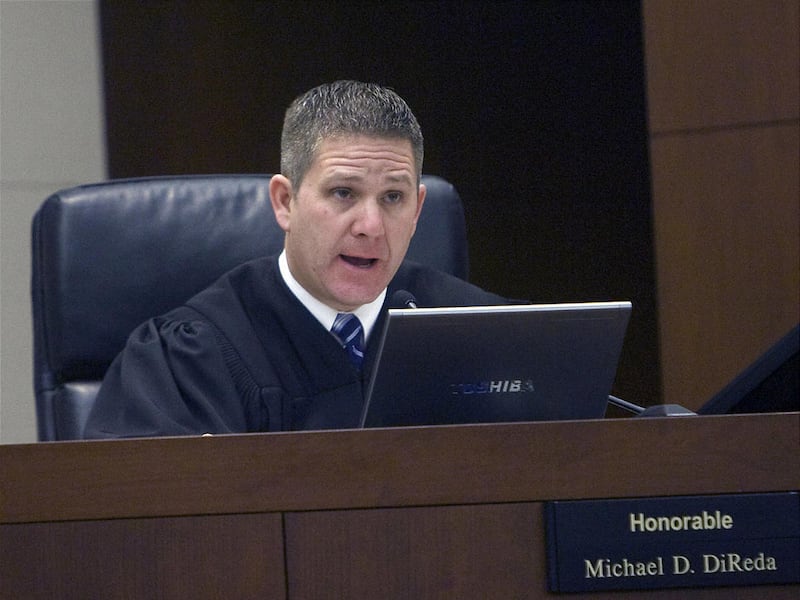

That evidence should be things like DNA evidence, a rock-solid alibi, irrefutable scientific proof or a confession from the real killer — none of which Brown has. Instead, her attorneys must weave together a string of circumstantial facts to persuade 2nd District Court Judge Michael DiReda by "clear and convincing" evidence that Brown is the wrong person.

Reed knows his position makes him look like the bad guy, but it's not a task he requested. When the law passed, he was handed the extra responsibility without any extra resources.

"We're all on the same team when it comes to the search for innocence," Reed said. "If (Rocky Mountain Innocence Center) is there as the safety net, I don't begrudge them that. And if they come to me with a case that screams out factual innocence, my obligation is to say, 'Let me show you to the governor's office. We'll all go together.'"

But until then, his responsibility is to defend the integrity of the system and the finality of judgments.

He acknowledges mistakes were made during the original police investigation, yet those mistakes don't automatically mean they got the wrong person, he said.

"Putting the police or (the former defense attorney) on trial for what he did or didn't do seems to me to evade the burden of the petition," he said. "Bring us the evidence that says you didn't do it, and we'll be the first one to give you the keys to the prison."

The Logan Police Department also stands by the jury's decision.

"We did our job in 1993 and we obviously did the job well enough...the evidence was compelling enough that (12 jurors) felt she was guilty," said Jeff Curtis, assistant police chief of the Logan Police Department. "We looked at every angle, we took every angle we could to put this case together and tried to (make) the people who were responsible for it ... face the consequences."

Yet, attorneys Martinez and Sullivan disagree, which is why since joining the case in 2009, they have worked hundreds of hours, unpaid. At the request of Judge DiReda, they will present two more witnesses at a March 7 hearing. Sometime after that hearing the judge will issue his ruling.

If he rules in Brown's favor, she could walk free, unless the state appeals. Reed said the state is undecided on an appeal at this point.

If the judge denies Brown's motion, Sullivan said they will appeal her case to the Utah Supreme Court.

"We all know that eventually she's going to get out, whether it's two months or two years," Ryan said. "I can't see it going any other way."

Moving forward

Ever since Rocky Mountain Innocence Center got Brown's case into court, her family has made up slogans to keep them positive while they waited.

Themes like, "2008 is going to be great," and "2009 will be just fine." This year of 2011 "is going to be like heaven," said Jessica Armstrong, Brown's niece and most devoted pen pal.

"That's what we've said, and I hope that's the case," Armstrong said, choking back tears.

Since she was 10 years old, Armstrong has made it a point to keep Brown in the loop about family events. She fills her letters with details of family gatherings and sends photos when she can. When Armstrong married seven years ago, she sent her aunt a wedding invitation.

"I try to write her every week," Armstrong said. "Just so she knows that we're here, that she's not forgotten and we'll never give up."

Although Brown has always been a warm, giving person, family members say the time in prison has softened her even more. Along with knitting hats and booties for LDS humanitarian efforts and her grandchildren, she has read the Book of Mormon several times. One of the first things she wants to do after getting out is be baptized.

Ryan laughs as he remembers allowing the LDS missionaries into their Logan apartment because he knew it drove his mom crazy.

"And here she is now," he said. "If she were able to go on a mission, I can't imagine how many people she would convert. It's just crazy, she's a completely different person."

And so is her family.

Son Josh Whitney, 30, values family relationships more, after realizing his mom's incredible work ethic and strength in the face of adversity.

Oldest child Ryan Buttars, 35, has gone from an angry, troubled teen to a hard-working father of five who also found strength and peace in the LDS church. Williams and Whitney lovingly refer to him as "amazing," and "the best" out of the three of them.

For daughter Alana Williams, 29 the experience has taught her patience, and to wait before passing judgment.

"I can't be mad, because I wasn't there, I don't know," she said of the case. "I don't want to place blame where it's not meant to be. It'd be great if we can find anything and everything that points in some other direction, but if it can't be beyond a reasonable doubt, I don't want that (guilt) placed elsewhere, because my mom's been through that, and I don't want anyone else to have to go through that."

Although Brown has been gone for 17 years, her children have matured and blossomed under her long-distance mothering. They've learned to let go of anger, and move forward with optimism, just like Brown has.

"A lot of people go through this life and they carry things with them all the way to their death and it's just sad," the shackled Brown recently told her attorneys, who told her family members. "But I have let everything go, and I am free."

e-mail: sisraelsen@desnews.com