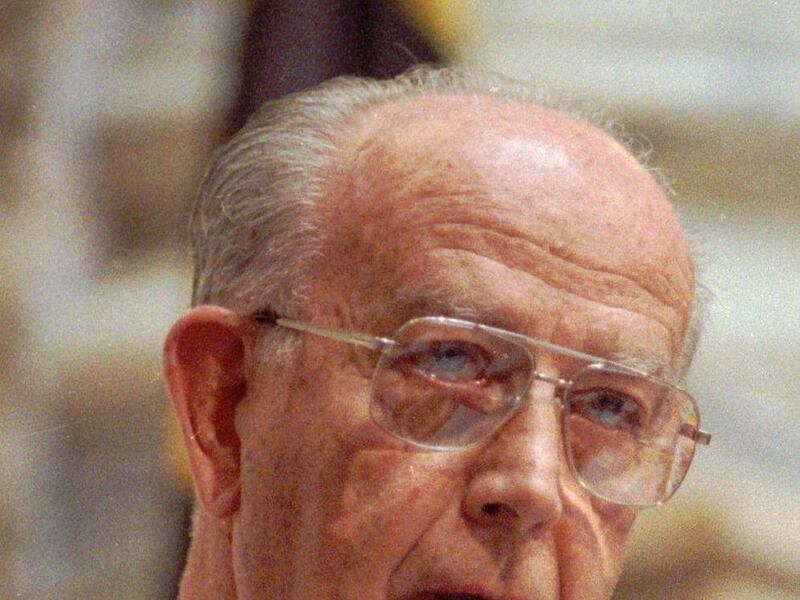

BALTIMORE — At the gateway to Baltimore's Inner Harbor, a bronze statue of William Donald Schaefer celebrates his tireless efforts on behalf of his beloved city: a thriving waterfront, an old-timey baseball stadium and a football stadium that helped the city win back an NFL franchise.

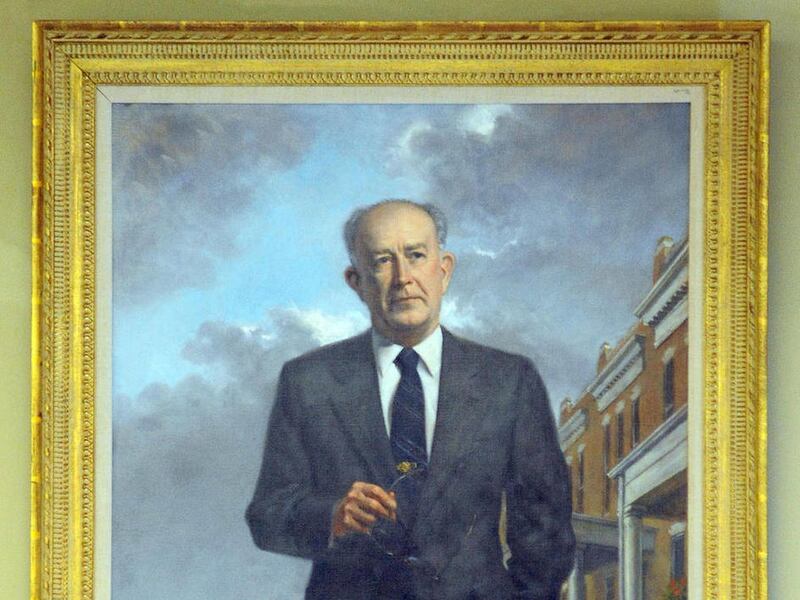

But for his mayoral portrait, the former son of Baltimore stands in front of a line of the city's tiny red-brick rowhomes, like the ones that lined the street where he lived in west Baltimore for decades with his mother.

Even when he moved up the ladder from Baltimore mayor to Maryland governor in 1987, he eschewed the illustrious governor's mansion in Annapolis during his first year in office, instead commuting daily from his city home.

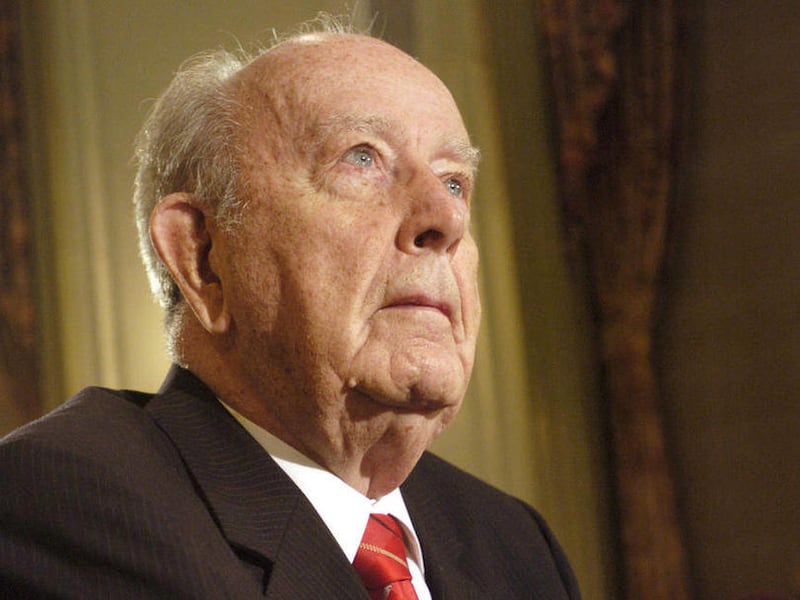

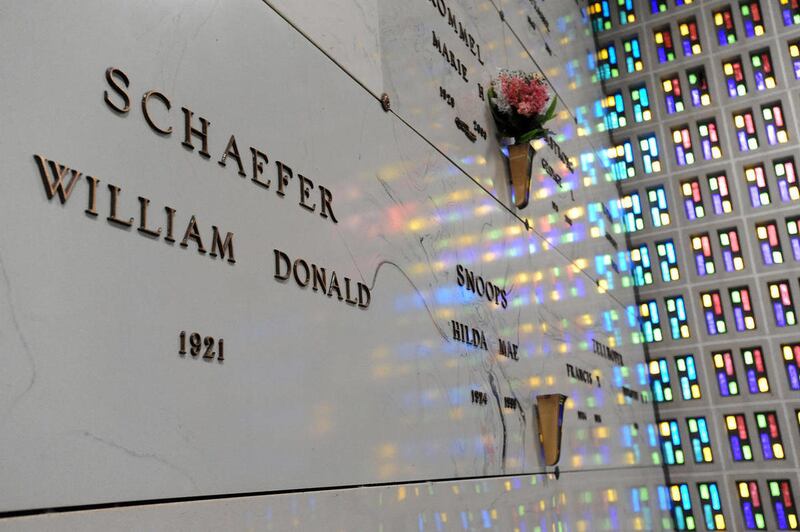

Schaefer, a political legend and icon in Maryland, died Monday at a retirement home in Catonsville after suffering from pneumonia. He was 89. A funeral service and burial are scheduled for April 27.

Throughout a career in public service that spanned more than a half-century, aides, colleagues and friends say he did big things for the little guy.

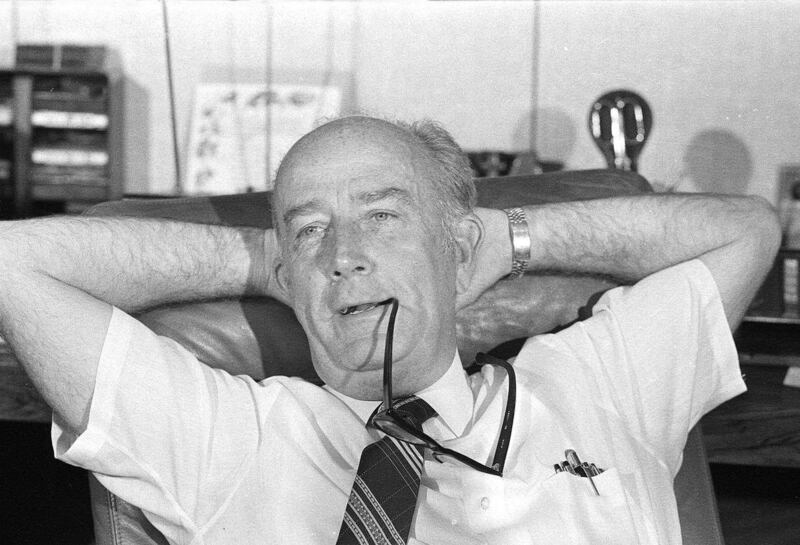

"Everything was big to him," said Mike Golden, who worked for Schaefer when he was governor and more recently state comptroller. "I don't think there was such a thing to him as small. He worried as much about filling potholes and clearing abandoned vehicles as he did about having the National Aquarium and the stadiums built."

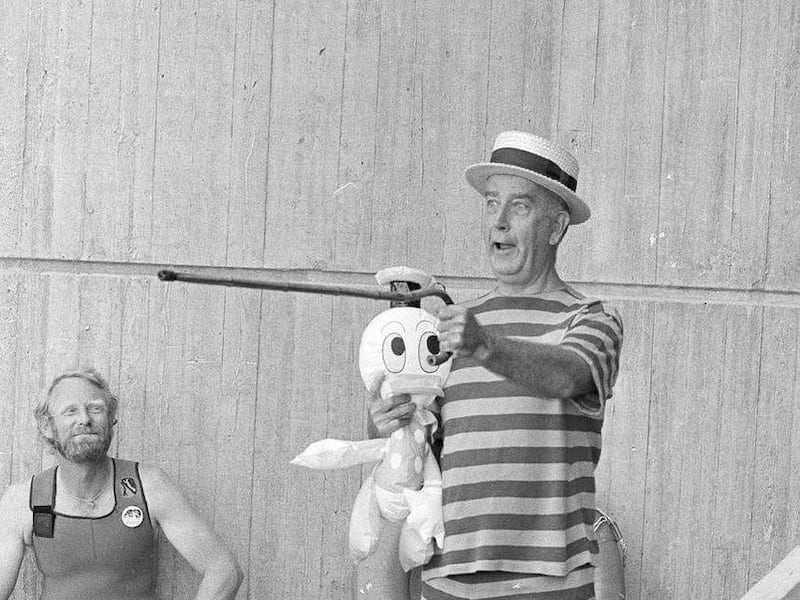

When Schaefer would put on a dog-and-pony show typical of any politician hyping public works projects big and small, reporters at first rolled their eyes, said C. Fraser Smith, Schaefer's biographer, who covered him for The Baltimore Sun.

When work on the National Aquarium in Schaefer's keystone Inner Harbor redevelopment stalled, he put on vintage yellow-and-red striped swimsuit, held onto a rubber ducky and tipped his straw hat as he waded into the seal pool. And when, as mayor, Schaefer wanted to sell Baltimore to the world, the city built a replica of a historic Clipper ship and dubbed the floating ambassador nothing less than the "Pride of Baltimore."

From any other politician, the moves would have been seen as stunts, Smith said. But from Schaefer, it was part of his persona.

With his drive and colorfully cantankerous personality, Schaefer made his perception of pride in Baltimore a reality, he said.

"He did the big because he knew the small would respond to it," Smith said.

Sandy Hillman, who served for 13 years as the head of the Baltimore Office of Promotion and Tourism during Schaefer's tenure as mayor, says Schaefer wanted to make Baltimore a tourist destination. He led the way in turning a grimy, post-industrial zone into a popular hub of shops, restaurants, museums and hotels.

"He wanted to be mayor to rebuild Baltimore," she said. "That's part of why Baltimore was so successful being what it was. I think that's part of the personality of the city. ... It's not a city of wannabes."

Schaefer believed that tourism could bring jobs to a city with undereducated and unskilled workers who needed work quickly.

"He had big ideas and he always believed that you could implement them if you tried hard enough," said Hillman, who now runs a public relations firm. "He always understood what people would gravitate to. That was part of his success."

The 1970s were a tough time for Baltimore and other older industrial cities, but the city's leaders at the time were part of a "renaissance of the gritty cities" and mayors of other cities came to learn from Schaefer.

"If he had not come on the scene in 1971, it would not be the town it is today," Hillman said.

Outside City Hall on Tuesday morning, Chris Williams, the communications director of the mayor's office of neighborhoods and a city resident, said Schaefer was a favorite son of Baltimore.

"I think of him as one of the city's most beloved characters," he said. "You hear people say there will never be another one like him again. ... We're going to miss him."

Supporters say Schaefer brought a tenacity to the job of building up Baltimore.

After then-Baltimore Colts owner Robert Irsay moved the football team to Indianapolis in 1984, Schaefer began lobbying for a new stadium to keep baseball's Orioles from leaving and personally worked on bringing the NFL back. Although Baltimore was passed over by the league during an expansion in the early 1990s, the city eventually attracted a previous Cleveland Browns franchise that became the Ravens.

"Cleary he felt that a big-league city had to have an NFL franchise and that without that Baltimore was at risk of losing its stature as a big league city," said Herb Belgrad, chairman of the Maryland Stadium Authority from 1986 to 1995.

Much of that drive was because the people of Baltimore, a gritty steel town, wanted football, he said.

"If you looked they were Schaefer's people," Belgrad said. "They were the little guy who needed somebody to look out for them, somebody in public office. Much of what he did was to help the average citizen."

More than 30 years after Schaefer unveiled a completely renovated Inner Harbor — with an open plaza, shops and a 28-story World Trade Center — residents came to a statue of Schaefer there to pay their respects Tuesday. Schaefer had attended the dedication just 17 months ago.

Kristin Collier left yellow roses at the foot of a bronze statue Tuesday morning. A note attached to the flowers read, "Harborplace and The Gallery will never forget you," referring to the shopping complexes that ring the harbor.

Although Schaefer drew fire over the years for his barbed comments, tirades and personal feuds, his former spokesman Golden says he elevated average citizens and made them proud to be from Baltimore.

When Golden began attending the University of Maryland in 1973, he wasn't sure whether he would return to his hometown of Baltimore. But when Schaefer sparked an urban renaissance — relying in part on the many ethnic festivals that are still held in city parks — Golden and others took a fresh look at the city they thought they would be running from.

"We all found pride in the city of Baltimore, and he did it," Golden said.

Throughout a life that was truly dominated by politics and public service — Schaefer was a lifelong bachelor, which longtime aides and colleagues attributed to his complete devotion to his work — the city itself became his family.

"I think the city was his family, and the city was happy to have him as its father," Smith said.