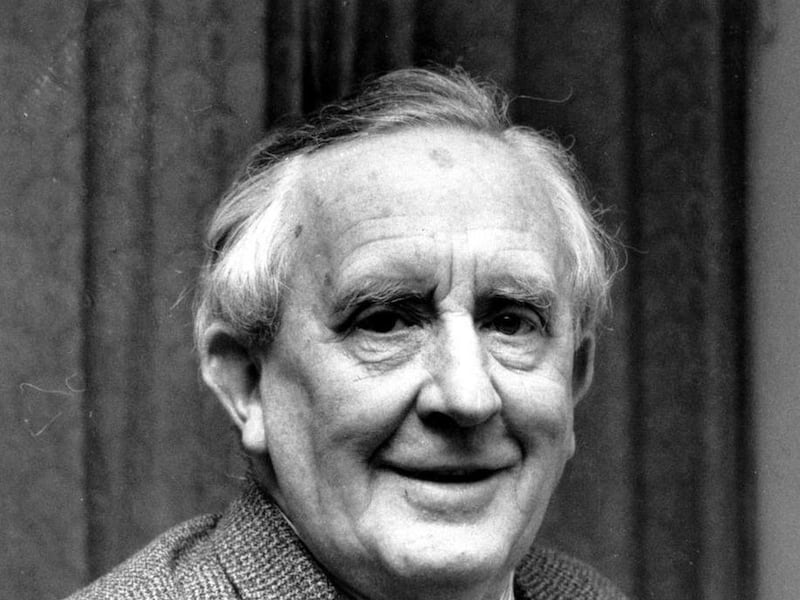

Before Peter Jackson stepped into Middle-earth, J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1954 epic “The Lord of the Rings” had already changed the world of fantasy, having sold more than 100 million copies and given birth to countless fans over multiple generations.

When it comes to adapting a novel for the big screen, though, fan expectations can be a major obstacle to overcome.

That’s especially true when the fans in question are as numerous and passionate as Tolkien’s.

Given some early attempts at bringing Middle-earth to life on the big screen, including one version that would have starred The Beatles (Paul as Frodo, Ringo as Sam, George as Gandalf and John as Gollum), fans had every reason to expect disappointment circa the 2001 release of “The Fellowship of the Ring.”

It was a movie genre seemingly doomed to mediocrity, with the most successful fantasy movie before “The Lord of the Rings” being 1988’s “Willow". The fact that this would be Jackson’s first foray into big-budget filmmaking was just salt in the wound.

In short, a movie adaptation of “The Lord of the Rings” had no right to be anything other than a disaster.

Instead, though, audiences were met with a sprawling fantasy epic completely unlike anything created before.

One film after another, “The Lord of the Rings” became a massive fan and critical hit, earning altogether nearly $3 billion, more than 250 film awards (including 17 Oscars) and being hailed as the greatest film trilogy of this generation.

Just as miraculously, Jackson’s films seemed perfectly geared towards both the Tolkien neophyte and the devotee alike.

So with the "Lord of the Rings" prequel "The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey" set to premiere next week, the question is, what made “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy so successful as a literature-to-film adaptation?

Back in 1998, Jackson spoke with entertainment site Ain’t It Cool News. Trying to assuage the fears of diehard Tolkienites up in arms over rumored changes, the director said, “You shouldn’t think of these movies as being ‘The Lord of the Rings.’ ‘The Lord of the Rings’ is, and always will be … one of the greatest (stories) ever written. Any films will only ever be an interpretation of the book. In this case my interpretation.”

No matter how slavishly Jackson had followed the original text, it would have been impossible to perfectly translate all 1,000 pages of Tolkien’s masterpiece to the big screen in a way that satisfied everyone.

After all, as critic Steven D. Greydanus of the National Catholic Register put it in an article on his website, The Decent Film Guide, Tolkien fans are an “almost comically diverse audience, encompassing Oxford literati in the 1950s, tie-dyed flower children in the 1960s, teenage role-playing gamers in the 1970s, conservative Catholics and other Christians in every decade, and countless more besides.”

Instead, Jackson focused on making the story work, first and foremost, as a film.

As any purists can attest, that meant taking major liberties with the source material. Characters are tweaked right and left, big chunks of the story like “The Scouring of the Shire” and Tom Bombadil are excised completely and much of the focus shifts to complex action set pieces like the Mines of Moria or the Battle of Helm’s Deep.

Unlike some movie adaptations, though, that doesn’t mean that Jackson and company used the novels merely as a jumping-off point and then made up their own story from there.

“We constantly referred to the book,” Jackson said, “not just in writing the screenplay, but also throughout the production. Every time we shot a scene, I reread that part of the book right before, as did the cast. It was always worth it, always inspiring."

Ian McKellan, who plays the wizard Gandalf in all of Jackson’s Middle-earth films, even went so far as to call their version “perhaps the most faithful screenplay adapted from a long novel.”

This is all the more remarkable considering how the project started. As Jackson, who cut his teeth with Z-grade horror comedies, originally pitched a “Lord of the Rings” adaptation to Miramax, Tolkien’s opus would have been pared down to two movies with a combined budget of only $75 million — less than most recent Adam Sandler comedies.

When Miramax suggested that one medium-length movie would be enough to cover all the major plot points, though, Jackson wisely took the project to New Line. There, he was encouraged to expand his vision.

The result? Arguably the most ambitious film production ever attempted at that time.

Shooting all three films simultaneously, Jackson had up to 20,000 people working under him, including more than 10,000 extras, making him at some points the single largest employer in all of New Zealand, according to The Economist.

Production included more than 48,000 pieces of armor, 19,000 costumes and 1,800 pairs of Hobbit feet created by the now-world-famous New Zealand effects company Weta Workshop.

Bringing a sense of legitimacy to the production, Jackson also hired two of the most successful Tolkien illustrators, Alan Lee and John Howe, to guide the design of every facet of Middle-earth.

In all of this, the filmmakers listened attentively to fans.

“Jackson himself interacted with movie webmasters and fans on a regular basis,” noted Garth Franklin of the movie news site Dark Horizons back in the early 2000s. “He’s extremely aware of fans and is making these films with them in mind.”

Underneath all the spectacle and bombast of Jackson’s CGI-enhanced Middle-earth, though, the films are particularly faithful to the books in one key way: Tolkien’s themes are left intact.

Rather remarkably, that includes an unmistakable Christian worldview.

During a press junket for “The Return of the King,” Jackson told one Christian group, "I’m not a Catholic, so I didn’t put any of that personally into the film on my behalf, but I certainly am aware that there were certain (religious) things that Tolkien was thinking of. … We made a real decision at the beginning that we weren’t going to introduce any new themes of our own into ‘The Lord of the Rings.’ We were just going to make a film based upon what clearly Tolkien was passionate about."

In some instances, Jackson highlights the Christian symbolism even more explicitly than Tolkien, like, for example, when Gandalf sacrifices himself to the demonic Balrog, falling with his arms outstretched in the shape of a cross.

“While not equaling the religious vision of the books,” writes Greydanus, “the films honor that vision in a way that Christian viewers can appreciate, and that for non-Christian postmoderns may represent a rare encounter with an unironic vision of good and evil.”

Of course, Jackson’s trilogy isn’t without its detractors. Among them, rather notably, is Tolkien’s youngest son and literary heir, Christopher, who has spent much of his life editing his father’s unfinished manuscripts for publication. In a recent interview with French newspaper Le Monde, the younger Tolkien, who just turned 88 this year, criticized the filmmakers, saying: “They gutted the books, making an action film for 15- to 25-year-olds.”

Jackson’s decision to adapt the slight, 300 or so pages of “The Hobbit” as a full-on prequel trilogy has also been met with raised eyebrows by some who see it as a blatant cash-grab.

Ultimately, though, the “Lord of the Rings” films have been successful for a reason both fans and detractors alike should be able to get behind, namely, the exposure they’ve provided Tolkien’s original masterpieces in the 21st century.

As one critic said shortly after the release of “The Fellowship of the Ring,” the world would now be divided into two types of people: “Those who have read ‘The Lord of the Rings’ and those who are going to.”

Since the first movie was released in 2001, Tolkien’s books have become more popular than ever. “The Lord of the Rings” has sold an additional 50 million copies and currently ranks as the third best-selling novel of all-time.

At No. 4, with more than 100 million copies, sits “The Hobbit.”

It’s anyone’s guess how many more of Tolkien’s books will sell between now and the conclusion of Jackson’s new trilogy or how many new fans will be created as a result.

A native of Utah Valley and a devoted cinephile, Jeff is currently studying humanities and history at Brigham Young University.