Sarah Taylor sat peacefully in the sanctuary of Coram Deo church in Eagle Mountain, Utah, normally a place of clarity and not confusion. The church's name, meaning "before the face of God," describes how Taylor tries to make her decisions — comfortable before his face. Worshipping with the family she lived with the Sunday following the 2008 presidential election, 13-year-old Toddy asked Taylor about one of those decisions.

"She asked who I voted for, and I told her I voted Democrat," Taylor reflected. "Then she just kind of laughed and said, 'Come on, who did you really vote for?'"

Noticing the confusion Toddy was experiencing, Taylor explained to Toddy that her Christian upbringing motivates her to vote Democrat, because of Jesus' teachings to care for the poor and love all people. She said her evangelical upbringing taught her to support people throughout all their lives, and "not just before they were born."

"We ended up talking about it for two hours and then for the next two years," Taylor said.

Toddy's confusion over Taylor's political decisions is no surprise in the United States, where terms like "religious right" and "moral majority" are used to characterize the socially conservative evangelical Christian base. Based on data compiled by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 77 percent of Caucasian born-again Christians voted for a Republican candidate in the 2010 midterm elections.

However, some argue there are major political differences among evangelicals inside and outside of the United States. Despite the Bible's claim of "one Lord, one faith, one baptism" (Ephesians 4: 5), the interpretation of that faith mobilizes some, like Taylor, to positions that may seem inconsistent with commonly perceived evangelical behaviors.

Paul Freston, CIGI Chair for Religion and Politics in Global Context at the Balsillie School of International Affairs at Wilfrid Laurier University, emphasizes this sentiment. Having done research on evangelicals all around the globe, Freston says the perceived uniformity of those characterized as evangelicals can be misleading.

"In the work I've done with evangelicals and politics around the world, I've always tried to emphasize their variety," Freston says. "Sometimes you get scholars or analysts who try to pigeonhole evangelicalism politically. What one sees around the world doesn't really support that. There is such a diversity within countries, and there is also a tremendous diversity between countries as well."

In his work, Freston quotes historian David Bebbington's four emphases to describe evangelical theologically: conversionism (need for change of life), activism (evangelistic efforts), Biblicism (special importance to the Bible, though not necessarily the fundamentalist idea of 'inerrancy') and crucicentrism (centrality of Christ's sacrifice on the cross).

However, he points out, the political stances and sway of evangelicals varies greatly on the political system of which they are a part.

"There are tendencies toward more democratic ideals because evangelicalism is voluntaristic and pluralistic, so it tends to strengthen civil society," Freston says. "But sometimes its direct political action is far more controversial, notably in Brazil, where there's been controversy surrounding very narrow political agendas seeking to strengthen church institutions and not really a political agenda for society at large."

Matt Marostica of the Stanford library has studied comparative politics, specifically the intersection of religion and politics in Latin America. He draws attention to the fact that a major difference between evangelicals in the United States and those of Latin America is this focus of political energy on strengthening church institutions, which puts evangelicals in a more progressive political role.

"In many places in Latin America, non-traditional churches — i.e. almost all of the evangelical denominations — were treated as representatives of foreign countries. They had to register with the state and they were subject to certain controls," Marostica says. "They were treated differently so they mobilized around having the same status of historic churches. That's pretty different than the U.S., where this is a Protestant country so the evangelicals frequently can be mobilized to try to get back to our traditional roots, making them conservative where they want to keep things as they were."

Marostica also points out that because evangelicals are among the poorer populations, their economic views also differ from the patterns of evangelicals in the United States. According to Peter Beyer and Peter Clarke's book, "The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations," Protestants (of which most are evangelical) make up around 12 percent of the Latin American population, disproportionately among the poor, less-educated and darker-skinned.

"For example in Argentina, if you gauge where they fall in the political spectrum by the parties with which they are associated, evangelicals in Argentina are all Peronists, because they are almost uniformly poor, and poor people vote Peronist," Marostica says. "It's not like evangelicals are being associated with a party of the right. They stay kind of left of center in their party affiliation because they continue to affiliate with the parties that are seen as representing the interests of the poor."

Although the majority of Caucasian evangelicals in the United States have consistent Republican voting patterns, some of the schisms among minority evangelicals surround economic issues because most conservatives don't support higher taxes, welfare, union organizing and other programs focused on the poor. Dr. Corwin Smidt, director of The Henry Institute of Calvin College, says evangelicals have different views about how to try to mend the gap of being socially conservative while still supporting the poorer populations.

"Evangelical Hispanics are much more Republican than Catholics, but they are ready to abandon the party for immigration and economic issues," Smidt says. "Others feel you vote in politics for cultural reasons but then in terms of addressing the poor and those type of commandments that evangelicals take seriously, they see that more through civil society — less through government and more through direct aid from churches to people in their congregations who need help. There are those evangelicals, however, who say that while that is helpful, it is not sufficient and government has to do its role."

Polling numbers show this schism as only 59 percent of evangelical minorities voted Republican in the U.S. 2010 elections compared with 77 percent of Caucasian evangelicals. However, the social conservatism of minorities should not be questioned, as shown in the exit polls from California's Proposition 8 balloting. Seventy percent of African-Americans voted for the same-sex marriage ban, while 53 percent of Hispanics did the same.

The clash of social conservatism against promoting government intervention for the poor is relatively unique to the U.S., according to Sam Reimer of Crandall University in New Brunswick, Canada. Reimer has studied evangelical differences across the U.S.-Canadian border and says while there are many similarities among the groups, politics look somewhat different.

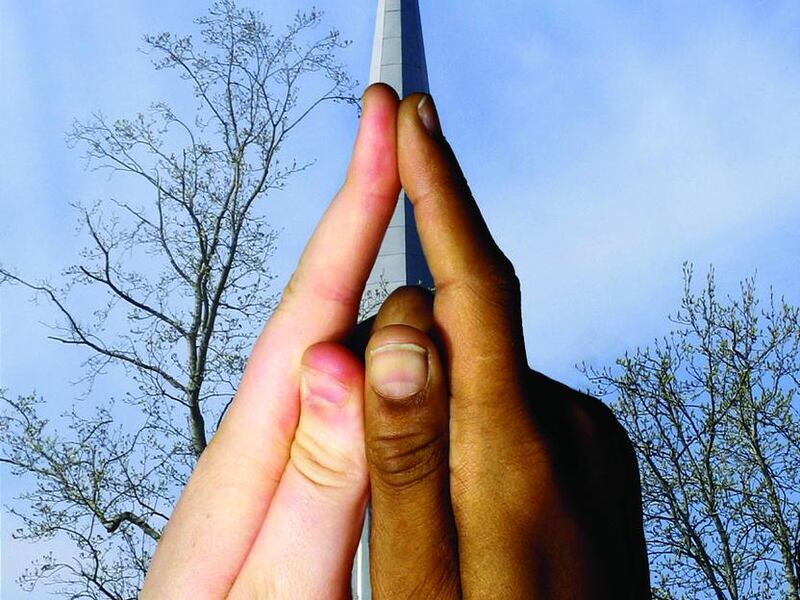

"The biggest difference is the alignment in the U.S. between conservative religious views and conservative political views. The same sort of alignment does not exist in Canada," Reimer says. "It's strange from the Canadian perspective because the conservative religious and political view are not necessarily linked. Evangelicals are very diverse when it comes to attitudes towards small government or concerns about welfare. In the last several decades, evangelicals have been a lot more concerned about the lot of the poor and racial reconciliation, which might sound like a liberal agenda."

Freston also emphasizes this disconnect between American evangelicalism's conservative politics and other evangelical politics across the world as well. One example he cites is the American conservative movement behind the 'war on terror,' in which 72 percent of American Pentecostals supported the war. In Latin America and South Africa, only around one-third of Pentecostals supported it, and South Korean Pentecostal support only reached 16 percent.

Yet Marostica and Reimer point out that social issues like abortion and same-sex marriage are almost uniformly opposed by evangelicals across the map. Both in Canada and Argentina, evangelicals have been mobilized to oppose social issues despite there being diversity in how they express that opposition.

"Here in Canada we have a low tolerance for intolerance," Reimer says. "While Canadians support socially conservative issues and would probably align with a party that supported those issues, I don't think that would ever happen because when things start looking too American, Canadians push away."

Freston says evangelicals' role in the political sphere has received mixed reviews. They have contributed in healthy ways to civil society, while in some countries they jump into the game too naively.

"Sometimes when evangelicals become involved in politics, they see themselves in a Messianic way," Freston says. "They see themselves sometimes as having all the solutions (even though) they have limited political experience and they don't know what they would do if they got into power. That can cause tension against the evangelical religious groups."

Email: jbolding@desnews.com