When you ask the (Darfuri) kids why are you in school? (They say) It will help me with my future; it gives me hope. Education is life-sustaining, not just life-saving. – Olabukunola Williams, program manager for Darfur Dream Team in Washington, D.C.

Someday, Rahma wants to return to his home country, which he fled after militia on horseback burned his entire village.

Why? So he can be president, of course.

A teenage Darfuri, Rahma is a refugee in Camp Djabal in eastern Chad, one of millions displaced from the Darfur conflict in western Sudan.

His presidential dream may be difficult to achieve — opportunities for refugees are typically bleak. Worldwide, the average refugee stays displaced for 17 years. If they do return to their homeland, they usually arrive years older, lacking the experience or skills necessary to build a new life. Children in refugee camps are especially at risk for recruitment as child soldiers or brides, and education programs are hard to sustain.

But Rahma has a school. What's more, he has friends in the U.S. — fellow students who support education in the refugee camps, thanks to innovative technology and a backpack of gear.

"Hi to all my friends of schools, how are you? Long time I never hear your joyful messages, I want to know your voice and what are you doing over there and your schools?" reads a post Rahma put on Pazocalo, a social media network built for Darfuris, advocates and students.

"Nowadays we’ve finish(ed) our holiday after five days of semester exam. We hope to continue study because we specially have (a) dream to change Darfur from the war and injustice to new Darfur."

Thanks to a collaboration between nonprofit groups i-ACT and Darfur Dream Team, students and educators in Chad and America are connecting through Pazocalo, building relationships and getting resources to further education in a remote, impoverished region — and developing a new generation of philanthropists at the same time.

"When you ask the (Darfuri) kids why are you in school? (They say) It will help me with my future; it gives me hope," said Olabukunola Williams, program manager for Darfur Dream Team in Washington, D.C. "Education is life-sustaining, not just life-saving."

How it works

Pazocalo resembles "a watered-down Facebook," but also boasts several innovations, according to Katie-Jay Scott Stauring, account project manager. Lots of white space and a simple, easy-to-navigate interface serves dual purposes: ease and cost-effectiveness.

"It's really developed for someone with low rates of literacy and no computer skills at all," says Stauring. "They don't have to navigate a desktop — it's developed for communities who don’t have knowledge of technology in general."

After logging in, users (students and teachers in the camps and at American "sister schools," as well as i-ACT volunteers) can create public posts, upload photos and videos (which are automatically compressed to save on satellite costs), leave comments and send individual messages.

Posts range from thank-yous to videos of soccer tricks and songs, classroom visits, camp projects and even videos of burning houses. American and Darfuri students ask each other what holidays they celebrate and what the weather is like.

At New Los Angeles Charter School, teacher Dan Thalkar came across the project while looking for a "connection with what's happening in the world" for a unit on human migration for his seventh-grade class. He signed up with the Darfur Dream Team.

In the first week of learning about Darfur and communicating with refugee kids who had fled the region, the students were already asking how they could help.

"(They said,) 'Why are you telling us all of this sad things when we can't do anything?’ ” said Thalkar. "They were already activists."

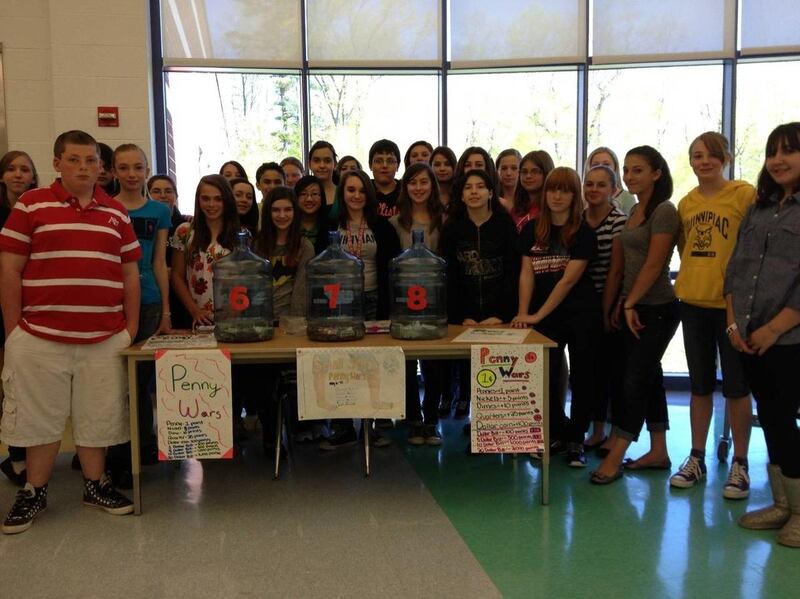

Through Pazocalo, Thalkar's students sent and received messages each day in class from Darfuri refugees. They also made and exchanged videos as a class with another seventh-grade classroom in a camp in eastern Chad. His students went on to raise about $1,200 through projects of their own design, including a bake sale and walkathon, for school supplies for that class.

Because of the personal communication and education, Thalkar said he saw excitement and curiosity in his students, "this overwhelming sense of wanting to learn more."

"'What is life like? How could this have happened? What can I do — why did my country not do enough?' … They made this issue their own. I'm amazingly proud of them."

An online peace square

Internet connection is typically a province of the relatively wealthy — worldwide, only about 20 percent in developing countries have access, according to the International Telecommunications Union.

But when Yuen-lin Tan, a Silicon Valley developer and technology adviser, visited Darfuri refugee camps in 2007 with i-ACT, a grass-roots organization based in California's Bay Area, he saw a way to make that change.

Seeing the isolation and desperate straits the refugees were in, Tan — someone his colleagues call a "tech ninja" — felt that being connected to the rest of the world was an essential human right.

"That kind of connection should be thought of as basic infrastructure — everyone needs it, like food, water," Tan said. "We can use technology to provide it quite easily today."

Tan and the team developed Pazocalo (Spanish for "peace" and "square") to do just that: provide a connection between those with stories to tell and those with ears to listen.

Another of Pazocalo's innovation is that it can operate offline.

"For sites like Facebook or Instagram, you have to be connected to use it," Stauring said. "(Pazocalo) can be used offline, and then once it's connected it will automatically send messages — you're able to save satellite costs by being able to use it offline."

While users in other countries can access Pazocalo on their laptops or other computers, the refugees use something different, called a "CommKit" — satellite modem, computer, cameras and a solar panel charging battery packs — all contained in a backpack.

Impact

Currently, Pazocalo's largest use is with social media's biggest fans — middle and high school students across the U.S., due to the partnership with the Darfur Dream Team Sister Schools Program.

Since 2007, more than 300 sister schools have teamed up with the Darfur Dream Team to connect with 12 schools in Darfuri refugee camps.

Funds raised by sister schools go toward furthering education in the camps, purchasing desks, tables, books, e-readers and sporting equipment (soccer and handball are hugely popular).

"When I went to the camps in 2007, there was one level-six class, no secondary school, no grades 7 or 8," says Stauring. "Since then they've added grade 7 and 8, secondary school, teachers, teachers at the primary school who have gone through secondary schools, (and) an increase in education for girls — for girls it's been pretty phenomenal."

Construction on a preschool center is also slated to finish this week.

Williams of the Darfur Dream Team said it's a two-way street, and the U.S. students benefit just as much.

"It's easy for me to say, oh I want to tell the stories of the refugees. But to have refugees telling their own stories — they can tell it better than I can," said Williams.

"It's really powerful for people in the U.S. to get to learn about the other part of the world, to learn about Chad, Darfur, Sudan, to learn about the African continent, to learn about people," she said.

And by putting human faces and personal friendships on the conflict, many of whom are using English and new technology for the first time, students learn to "recognize the humanity in each other."

In addition to the Darfur Dream Team sister schools, Pazocalo is also used to connect Darfuri refugees to a doctor and a nurse, an assessment expert and early childhood education experts.

Ideally, Stauring would like to use it to connect journalists, advocates and policy-makers to those most in need — all over the world.

"It's unique to the Darfuri refugee camps right now, but we've been working to reach out and have it deployed to other areas," said Stauring. "We'd like to see the CommKits be deployed at the beginning of (all) emergency humanitarian situations."

Obstacles

One barrier to such implementation is cost — according to Stauring, a single CommKit can run about $5,000. It's about $6 a megabyte to send/receive text, photos or video from eastern Chad, which can add up quickly, even with the video compression and bare-bones interface.

And refugee education can be an open-ended investment, especially in the case of Darfur, where violence has increased in recent months and the region shows no sign of refugees being able to return home. A surge in fighting has displaced another 300,000 Darfuris since the beginning of the year, and humanitarian officials worry about the strain on Chad's people and resources in the area.

But when it comes to long-term conflicts, continuous, personal interactions may be the only thing sustaining interest.

"Personal connection is the reason that interest is sustained and why those school groups don't move on to other issues," said Stauring. "I really believe that the personal issues keep those schools engaged."

And when the next generation of advocates stays engaged, and refugees are able to share their stories and keep their voices heard, there is hope for peace in the region.

In the meantime, victims of genocide can get an education that will prepare them for their lives — wherever they may lead. And who knows? Maybe one day Rahma will be president of Sudan.

EMAIL: kbennion@deseretnews.com

TWITTER: @katebennion