Something in me was so deeply touched by the suffering, grief and loss. I went to a very dark place and stayed there for a long time, a mixture of depression and burnout. I say 'burnout' because I lost hope in the work I had come to do. – Marianne Elliott

When Marianne Elliott took a job in Herat, Afghanistan, she expected difficulty.

The human rights lawyer from New Zealand had worked in the Gaza Strip, Timor-Leste and Kabul. She had come to do good, and to do it in a war zone.

But while she was still adjusting to her new job with the U.N. and its duties, senior officers took leave and left her in charge of the U.N. peacekeeping mission office. On her very first day in charge, a local tribal elder was killed, and the area escalated quickly into a violent tribal conflict.

"It was just the worst possible scenario," Elliot said.

Elliot handled her responsibilities fine, but the inherited trauma from those who lost loved ones was intense — 140 people were killed.

"Something in me was so deeply touched by the suffering, grief and loss," she said. "I went to a very dark place and stayed there for a long time, a mixture of depression and burnout. I say 'burnout' because I lost hope in the work I had come to do."

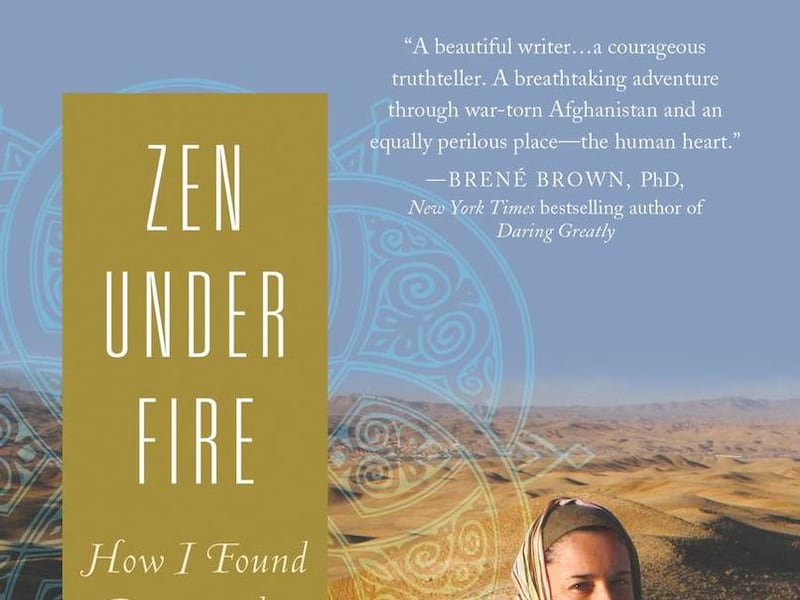

Elliot is the author of a new book, "Zen Under Fire: How I Found Peace in the Midst of War," and while her experience in Herat took place under extraordinary circumstances, burnout is a common problem among volunteers and those who deal with those affected by trauma. The experiences of Elliot and others like her raise questions about how organizations, nonprofit groups and relief workers can take better care of humanitarians.

The importance of self-care

Burnout is common in situations like Elliot's. A 2012 CDC study found that among international humanitarian workers around the world, rates of depression doubled after deployment — and rates of anxiety quadrupled. The rates can rise even higher in high-risk areas: a Columbia study of a humanitarian organization in northern Uganda found that 68 percent of workers experienced depression and more than half had anxiety.

Kimberly Williams is an associate director with Lasallian Volunteers, where she works with recent college graduates who spend a year serving the poor in schools and agencies of the De La Salle Christian Brothers. She said burnout is a problem among many people who work with trauma victims or in other stressful relief situations.

"A lot of people come in with really great intentions to give sacrificially and care for other people, and then they get to the point where they say, 'I need to leave,’ ” Williams said. "In order to stay involved for the long haul, as a leader you need to care for yourself."

Williams compiled and created materials for a self-care toolkit for urban workers in coordination with the Fuller Youth Institute. The toolkit contains articles, podcasts and recommendations on regular practices to facilitate resting and processing experiences.

Such self-care can look like different things for different people. For Elliot, a solution came in a previously ignored yoga CD her friend had given her to take to Afghanistan.

"(I learned you need to) allow yourself to feel what you're feeling," said Elliot. "One of the things I did for a long time … I would say to myself, you don't have the right that you're struggling with because you're so much better off than the people you're here to serve. As long as I denied it, it was unresolved and took its toll on me. If you're having emotional responses to what you're seeing, hearing, your first instinct might be to deny your own rights to have an emotional or physical reaction — because you think, 'Who am I to be having a breakdown?’ ”

That reaction is harmful, Elliot said. "Trauma does have an effect on you. If you can allow yourself to have the reaction that you do that's going to be a really helpful start."

According to Williams, care workers can experience trauma-like symptoms, even if they weren't present for the initial trauma.

"Care workers sometimes experience their own personal trauma," Williams said. "They take on a lot of trauma from walking with other people. In studies it's almost as if they … experience trauma that didn't happen to them."

Practices such as journaling that help to process and let go of that absorbed trauma are also crucial. For Elliot, the practice was meditation.

"Meditation helped me a lot in the presence of difficult, unpleasant emotions, to let them come and go again. … I could see how when I was swinging between turning away from it or trying to put a boundary or barrier up, I got pulled into it, I was holding it, it was sticking with me. What the yoga practice and the meditation practice helped me find was to allow myself to be open, to feel it, but to keep moving, because it wasn't mine to hold."

"She's cracking up."

Self-care and burnout are considerations organizations need to take into account as well — especially those struggling with volunteer or worker retention.

"We need to take good care of ourselves, but in order to do that, there needs to be kind of organizational, cultural support for that," Elliot said. "Even when organizations put things in place, like a staff psychologist, it's very rare for people to use those because the culture as I experience it suggests that if you can't cope there's something wrong with you, that you should be able to cope."

Elliot shared a story from her Afghanistan experience in which workplace culture let her down.

Working as the sole international staff member in a remote office and living alone, she was a two-day-drive from the nearest office. One night, as she stayed in the compound alone, there was an attack. Large, rocket-propelled grenades were fired at the compound.

"They didn't land in the compound, but they were very close, very frightening," said Elliot.

Elliot spent a rough night in the bunker, and the next day, for the first time in her Afghanistan experience, she didn't go into the office.

"I just said, 'I'm at the end of my wits, I need a day in bed.'"

Later Elliot heard another co-worker saying that Elliot was not coping, that she was "cracking up."

"I felt so ashamed," said Elliot. "I look back now and I think, how dare they. (I had) no one to talk to, been through this very frightening grenade attack, no one calls me ... instead they gossip about me."

The culture of "if you can't cope, you're not cut out for it" needs to change, according to Williams. She said humanitarians need to pace themselves and organizations need to give them room to do so.

"If you feel like you want to be involved when you're 80, you have the time to go slow and nurture relationships slowly," said Williams. "There are so many things in our life that cause us to experience grieving … (We need) to give people and their minds, bodies, spirits, emotions the space to run that course rather than just trying to be normal or better or fine."

A study published by PLoS One found that one factor that eased burnout among relief workers included more autonomy and control over their jobs. Those with strong support networks also reported less depression, anxiety and burnout.

Sara Bowers Posada worked in Afghanistan with Catholic Relief Services. She said she saw burnout in herself and in her colleagues.

"It definitely took a toll," Posada said. "We didn't have a way to support each other because we didn’t have a name for what was going on."

Posada said in high-stress situations, it's important for organizations to be honest with their employees and allow space for emotional care. "For me it's about having that upfront conversation about how this can affect you," said Posada. "It's very addictive because you know your work is really important and it's really hard to step away and say, 'I can only do this work well if I take the time for myself.’ ”

Catholic Relief Services, for example, required its workers in Afghanistan to leave the country every few months for a brief respite, a practice Posada said helped tremendously.

Sharing stories

Despite Elliot's "dark and difficult" time, she decided to stay — and stayed for two years.

"I decided I (wanted to) get better and make some useful contribution to Afghanistan," said Elliot, "to learn a lot about myself and how to be among suffering without being overwhelmed by it."

Elliot left Afghanistan in 2009, but part of the motivation for leaving was to share the stories.

"(An Afghan colleague) told me, your job is never finished. Part of your job is to tell the stories you've seen and been part of here," Elliot said. That was her motivation to write the book.

"I think her book is going to be great conversation starter for humanitarians," Posada said. "First and foremost we need to have our hearts with Afghans, folks who are living there, who are leading full and wonderful lives but who also don't have the ability we have to leave that violence behind."

"For me that's really been the struggle: how do I keep that compassion at the core (while still taking care of myself)? How to keep that compassion alive in a healthy way is really the critical work. (Elliot) has struggled with these questions so intensely, and thorugh her writing and other ways has figured out a way that works really well for her and hopefully for other people as well."

EMAIL: kbennion@deseretnews.com

TWITTER: katebennion