PROVO — American cars have an obesity problem, but a pair of BYU professors and their collaborators believe they may have found an appropriate vehicle weight-loss program — friction bit joining.

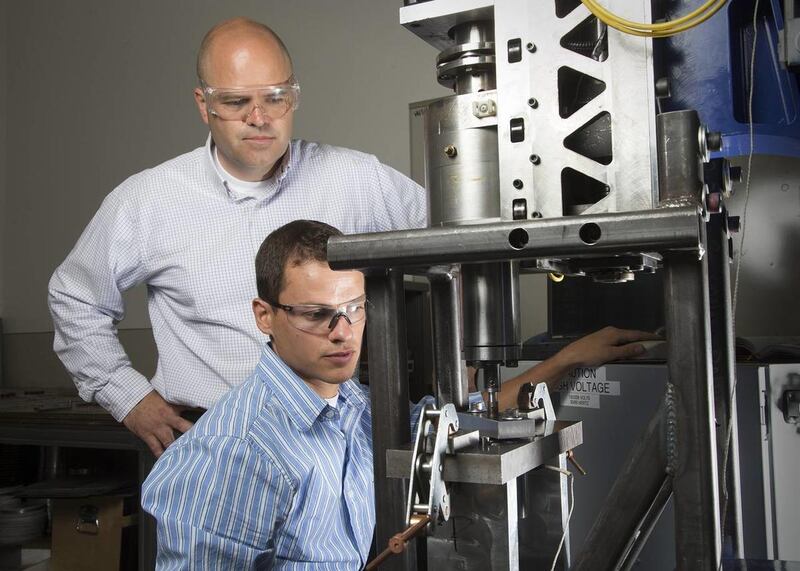

Friction bit joining is a relatively new manufacturing technique that uses friction to permanently bond two overlaid metals. Unlike other forms of joining metals, like welding or riveting, friction bit joining is uniquely capable of bonding dissimilar metals that usually refuse to meld, such as aluminum and high-strength steel.

Car manufacturers looking to meet federally mandated standards for fuel efficiency have recently introduced designs that call for bonding lightweight metals to high-strength materials, particularly in the frame of the cars. Without a method to effectively bond dissimilar metals, the design remained mostly theoretical. The automotive industry has in recent years effectively incorporated aluminum into some car designs, but the technologies in use are inappropriate for joining aluminum to ultra-high-strength steel.

However, BYU's friction bit joining can effectively bond aluminum to ultra-high-strength steel, according to a study published last month in the International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing.

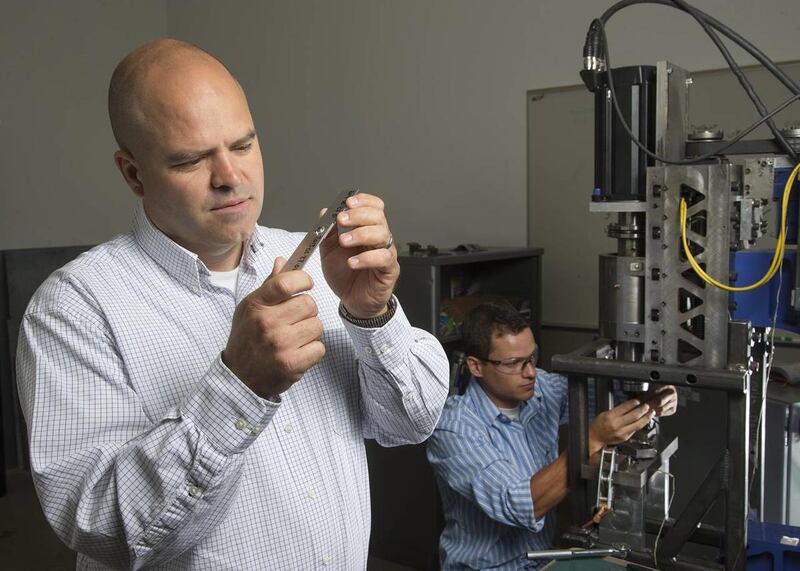

Michael Miles, a professor of manufacturing engineering technology, and retired BYU professor Kent Kohkonen began developing the friction technique in 2006. Scott Packer, a part-owner of Orem-based MegaStir Technologies, came to BYU to propose a collaboration on the technique when he stumbled upon the idea while working in his own workshop, Miles said. MegaStir and BYU worked together on the development, and other collaborators joined them as the new technique's potential became more apparent.

Though Miles and his collaborators have focused on applications within the automobile industry, friction joining's ability to bond dissimilar metals could interest aerospace and many other industries as well, Miles said.

"It's something that would be on everybody's agenda," he said.

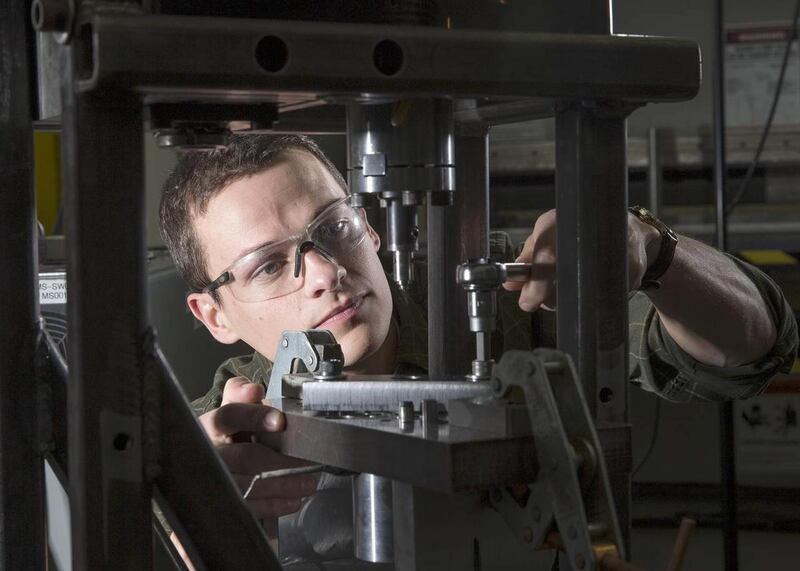

There are still a number of issues to consider before friction bit joining will see widespread use, Miles said. Among them is the economic feasibility of incorporating the technique into production lines. Friction joining currently requires human operators, and Miles said one of the next steps for his collaborators is to find a way to automate the process.

Even if they can find a way to make the new technique commercially feasible, Miles said he expects the automotive industry would likely incorporate friction joining a little at a time to test the bonds. Over time, he said, he expects the technique could have a significant impact on the fuel efficiency of a variety of vehicles simply by decreasing the weight of the frame.

EMAIL: epenrod@deseretnews.com