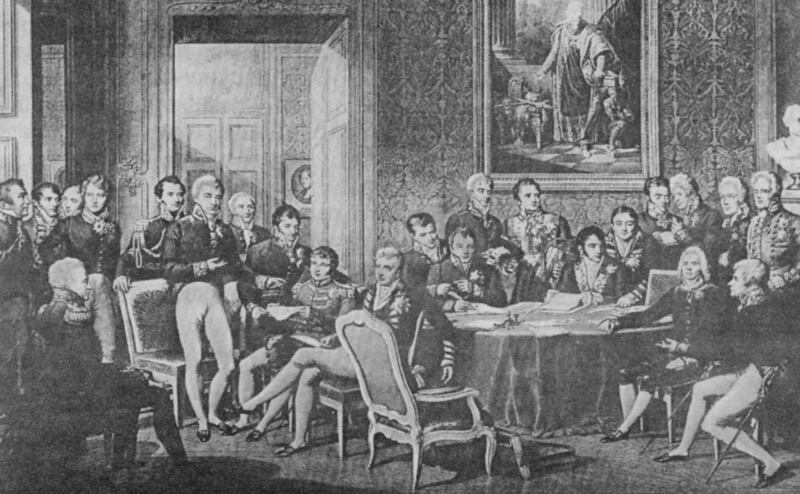

Two hundred years ago this week, monarchs and ministers from around Europe descended upon the Austrian capital for the Oct. 1, 1814, commencement of the Congress of Vienna. The congress was called in order to adjust the borders of Europe following Napoleon Bonaparte's abdication earlier that year, though ultimately it had far greater significance and determined the political order of Europe for nearly a century.

Most European monarchs viewed the 1789 commencement of the French Revolution as the unleashing of chaos upon Europe. The French had deposed and then executed their king, and by and large European monarchs had closed ranks in order to fight the pariah nation. France, with its wealth and vast reserves of manpower, proved more than a match for the various coalitions that stood against it.

When Napoleon abolished the fledgling French Republic and declared himself emperor in 1804, the European monarchs believed that France had swapped the anarchy of revolution for the heavy hand of a usurper tyrant. In any event, Napoleon became their enemy. Though occasionally forced into an accommodation with France after military defeat, most monarchs continued to view Napoleon unfavorably and hoped for his downfall.

That event arrived in the spring of 1814. With Russian, Prussian and Austrian armies invading northeast France, and with British, Spanish and Portuguese forces advancing across the Pyrenees in the south, Napoleon's court urged him to abdicate. Aware that his situation was untenable, and acknowledging the generous terms the Allied coalition offered him personally, the usurper tyrant agreed to step down.

Elated at Napoleon's downfall, the various European monarchs decided to redraw the map of Europe, effectively detaching much of what Napoleon had conquered from France. In order to achieve this aim, and considering many other questions that would have to be addressed, the monarchs decided that they would meet in Vienna for a peace conference.

In the book “Vienna, 1814: How the Conquerors of Napoleon Made Love, War and Peace at the Congress of Vienna,” historian David King wrote: “The Hapsburg Capital was a good choice for the world meeting. Geographically and culturally, Vienna was the heart of Europe. Until as late as August 1806, Vienna had been the center of the Holy Roman Empire, the gigantic, ramshackle realm that had been dismantled by Napoleon. … The Holy Roman Empire was no more. Imperial majesty and grandeur, however, had far from faded.”

Though the Austrian emperor, Frances I, nominally hosted the congress, the man who dominated the proceedings was his foreign minister, Prince Klemens von Metternich, a skilled and experienced diplomat who was determined to create a new European order. King wrote:

“Metternich seemed lazy, vain and irreverent, but it was also true that he deliberately cultivated his image of gentlemanly nonchalance. He liked to pose as a playful and idle dabbler, while at the same time he waged diplomacy like a game of chess and did whatever it took to win.”

The various representatives and delegates from around Europe began to arrive in Vienna as early as mid-August and their numbers swelled by late September. British Foreign Secretary Robert Stewart, known as Viscount Castlereagh, represented the United Kingdom. King Wilhelm III led the Prussian delegation, which also consisted of notable diplomats Karl August von Hardenberg and Wilhelm von Humboldt, the scholar who created Prussia's education program, which is the basis for modern education systems used today.

Alexander I, czar of Russia, led his nation's delegation. France, long the pariah nation of Europe, now boasted a restored monarchy in the person of Louis XVIII, younger brother of the beheaded Louis XVI. Representing his new king stood Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, the ultimate political survivor who had served Louis XVI, a succession of revolutionary governments, Napoleon, and now the restored monarchy.

The work of creating a post-Napoleonic order for Europe began on Oct. 1, though many of the diplomats had still not arrived. The Treaty of Fontainebleau, the instrument of Napoleon's abdication in April, called for the peace conference, but did not specify an exact date for it to begin. Unlike the Paris Peace Conference over a century later, the meeting of the congress proved to be an almost lackadaisical affair.

In the book, “The Age of Napoleon,” historian J. Christopher Herold wrote: “The famous Congress of Vienna … never met in a formal sense. There was no official opening, no plenary session, no speeches were made, and the entire work was accomplished by small committees or behind the scenes.”

Over the course of the next nine months, the congress dealt with various geographical issues, political issues, ethnic issues and more. The congress saw its share of love affairs and scandals, such as the romance between Metternich and the beautiful Duchess of Sagan. It saw Beethoven's music coming to the attention of the international public for the first time. It saw the Austrians adopt the Prussian custom of placing a pine tree inside their homes for Christmas, leading delegates from other nations to do the same.

The congress would even have to deal with Napoleon's return to Paris in early 1815, and the subsequent invasion of Belgium, which culminated in the Battle of Waterloo. Eventually, the British victor of that battle, the Duke of Wellington, would replace Castlereagh as Britain's representative to the congress.

The early days of the congress, however, produced little in the way of agreements or accord. Herold noted that the congress, “during its first weeks appeared to be reluctant to address itself to even the most immediate problems facing it. The superficial observer could see nothing but a succession of balls, receptions, parades, concerts, and gala performances.”

Still, Metternich had his agenda. More than anything, the Austrian foreign minster wanted two things from the congress. First, he wished to create a conservative order in Europe, essentially rolling the clock back to the pre-1789 world where a nation rested upon the traditional props of monarch, church and aristocracy. To this end, he urged the other monarchs of Europe to create a form of collective security, in which they would support each other in the event that any of their nations should experience a French-style revolution.

Metternich sought to crack down on the various political and social forces unleashed by the French Revolution, including democracy, nationalism and classical liberalism. Metternich's second goal was to restrain a potentially powerful France and secure the general peace of Europe.

In these goals, Metternich proved partially successful. With the other monarchs agreeing to support his conservative policy, Europe largely stifled revolutionary activity before it threatened the new order. Often censorship, spies and brutal police tactics were used to combat actions seen as revolutionary.

This form of collective security proved successful until the year 1848, more than 30 years after the end of the congress, when revolutions spread throughout Europe and as far away as Brazil. Metternich remained at his post until that fateful year, when revolution in Vienna forced him into exile, before he finally returned to Austria to die in 1859.

Perhaps the congress' greatest legacy, however, is its success in preventing a general European war. The 19th century saw its share of conflicts between nations — the Crimean War, the Prussian-Austrian War, the Franco-Prussia War — but never again did the century see a conflict as large or as all encompassing as the Napoleonic Wars. Indeed, the next such struggle did not occur until 1914, when the guns of World War I began their deadly work.

The Congress of Vienna, it can be said, was responsible for 99 years of general peace in Europe.

Cody K. Carlson holds a master's in history from the University of Utah and teaches at Salt Lake Community College. An avid player of board games, he blogs at thediscriminatinggamer.com. Email: ckcarlson76@gmail.com