On Dec. 1, 1934, Sergei Kirov, the leader of the Leningrad Communist Party, was shot dead in the Smolny Institute. A popular Bolshevik and possible threat to Joseph Stalin's leadership, the circumstances of his death remain a mystery.

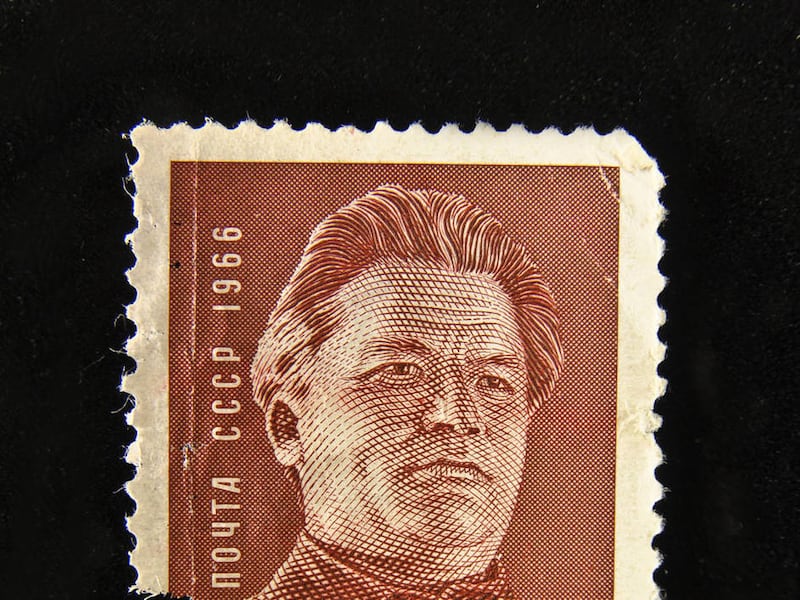

Sergei Mironovich Kirov was born in 1886 in Urzhum, in central Russia. Drawn to revolutionary politics, Kirov participated in the 1905 Russian Revolution against the czar's regime. He joined Vladimir Lenin's movement in the wake of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, and took part in Russia's civil war as anti-Bolshevik elements attempted to overthrow the burgeoning communist regime.

After the death of Lenin in early 1924, Stalin maneuvered himself into a position of power. While the Soviet State still practiced a theoretical collective leadership, by the end of the 1920's no one could openly move against Stalin and expect to survive politically. Many who had opposed him, like rival Leon Trotsky, had been exiled, and many more had been arrested. The worst was yet to come for victims of Stalin's paranoia, however.

Throughout Stalin's rise to power, Kirov had been a loyal supporter. The early 1920's saw Kirov working in the Bolshevik party leadership of Azerbaijan. An adept party organizer, Kirov was elevated in 1926 to the post of leader of the Leningrad party. Leningrad, formerly St. Petersburg, had been the Russian cradle of Bolshevism and the city that bore Lenin's name had become a symbol to many communists. Kirov's new position carried with it significant prestige.

To be sure, Kirov didn't fit the mold of a typical Soviet leader. He liked to live the high life, as much as a communist of the time could. He drank too much, and swore. His habits often flew in the face of the more puritanical leaders of the USSR. Still, he enjoyed widespread popular support. Many Leningrad workers and party members saw Kirov as approachable, almost like one of their own.

In early 1934, the 17th Party Congress met in Moscow to address political issues of the day and to celebrate the “success” of the First Five Year Plan, an economic industrialization program that had resulted in numerous deaths and arrests throughout the Soviet Union. Because of the propaganda that the plan had worked, however, the Soviet newspaper Pravda labeled the congress the “Congress of the Victors.”

Many delegates to the congress, however, had become critical of the regime's brutal excesses under Stalin, and some voices in the Soviet leadership, like G.I. Petrovsky, Sergo Ordzhonikidze and I. Vareikis, felt as though the need for Stalin's heavy hand had come to an end, and began casting about the idea, very carefully, that perhaps a new leader for the USSR might be desirable. This cabal approached Kirov about possibly assuming the mantle of leadership, but he demurred.

In fact, Kirov spoke of it to Stalin, bold enough to tell him that he had brought such conspiracies on himself, by his drastic measures at agricultural collectivization and industrialization. Toward the end of the congress, the 1,225 voting delegates cast their votes for members of the Central Committee, the party's executive organ through which Stalin exercised his control. Ballots had a number of names on them, and delegates simply crossed out the names they didn't want and left alone those they did. When the ballots were counted, it was found that 166 were missing.

In the book, “Who Killed Kirov? The Kremlin's Greatest Mystery,” historian Amy Knight wrote: “When the results of the voting were announced to the congress on 10 February, Stalin received 1,056 (out of 1,059) in his favor, while Kirov received 1,055 favorable votes. But three members of the voting commission … recalled years later that Stalin actually received a substantial number of negative votes — many more than Kirov.”

Undoubtedly, the vote was rigged. Though Stalin certainly would have remained in his position without the fraud, for political reasons he believed he had to be seen as receiving more votes than any other member. To Stalin's mind, Kirov's popularity now seemed to be a political threat.

Not long after the close of the congress, Stalin offered Kirov an important position in Moscow, presumably to keep him close. Kirov, however, refused the offer and requested to remain at his post in Leningrad. Friction between Stalin and Kirov continued throughout the year. In the book “Stalin: Breaker of Nations,” biographer Robert Conquest wrote:

“Stalin and Kirov had various quarrels. Kirov had to some extent dragged his feet over collectivization, with a smaller proportion of farmers in his area collectivized than elsewhere. … Kirov and Stalin also had a direct confrontation, with angry words (witnessed by Khrushchev) over Kirov allotting extra food to the Leningrad workers (on the grounds that this would improve productivity, a logic far different from Stalin's own). At any rate, Kirov was an obstacle, and he represented a mood hostile to any increase in Stalin's power.”

On Dec. 1, Kirov was attending to his duties at the Smolny Institute, a former girls' school and the Leningrad Communist Party headquarters. In the afternoon, he was walking down the main corridor of the third floor when, according to historian Alla Kirilina, Leonid Nikolaev, a 30-year-old former party member, emerged from a restroom, waited for Kirov to pass, then followed him several feet. Finally, Nikolaev produced a Nagan revolver and fired at Kirov from behind, hitting him in the back of the neck.

The same account states that Nikolaev turned the gun upon himself, but before he could fire an electrician threw a screwdriver at him that caused the would-be suicidal shot to go wild and sending the assassin to the floor. Kirov's bodyguard, distracted downstairs, emerged in the corridor and subdued Nikolaev.

As Knight has demonstrated, however, this account, as well as the findings of the Soviet Union's supreme court in the 1990's, leave many of the details quite vague. The fundamental question that has never been answered is this: Did Nikolaev act alone? Or was he involved in a plot by Stalin to take out a popular rival?

Supposedly, Nikolaev had his own motives. Nikolaev had been expelled from the party for his inability to perform his duties in various posts, and had been unable to secure another job. Also, as Stalin biographer Robert Service has alleged, Kirov had had an affair with Nikolaev's wife. Perhaps Nikolaev did indeed act alone.

Several theories don't add up, however. Several weeks before the assassination, Nikolaev had been loitering in front of the Smolny Institute. Upon his arrest the loaded Nagan revolver was found in his briefcase — and carrying an unauthorized handgun was a serious crime in the Soviet Union at the time. Yet Nikolaev was not only released, the weapon was returned to him.

Nor do we know what Kirov's security was doing during the murder. Conquest writes that Kirov's bodyguard, Borisov, “was detained at the front door.” Further, Borisov himself was murdered by NKVD men (Soviet secret police) before he could testify at the investigation into Kirov's murder. Within a few years, the Leningrad leaders of the NKVD, responsible for party leaders' safety, were also shot.

Whoever was responsible for the death, Stalin proved the ultimate beneficiary of the assassination as no one else in the USSR had the personal popularity to oppose him. Perhaps anticipating the political maxim of Rahm Emanuel, “Never waste a crisis,” Stalin frequently used complicity in Kirov's murder as a trumped-up charge against his enemies. During The Great Purge of 1937-38, Stalin's show trials sent numerous Soviet leaders to concentration camps or to their death.

Many of the delegates from the 17th Party Congress were among those liquidated in Stalin's purge. “The Congress of the Victors” soon became known as the “Congress of the Victims.” Of the 1,966 voting and non-voting delegates that attended the congress in 1934, 1,108 would be arrested during the purge.

Despite Stalin's brutality and lack of moral scruples, what part he played, if any, in Kirov's murder remains a mystery that historians continue to debate to this day.

Cody K. Carlson holds a master's in history from the University of Utah and teaches at Salt Lake Community College. An avid player of board games, he blogs at thediscriminatinggamer.com. Email: ckcarlson76@gmail.com