Gump entered the language. When you say someone is a Forrest Gump, that is a known subject. He may not be terribly smart, but he is kind and honest and compassionate. Things may go badly for a while, but he's got perseverance. So you've got King Lear, and David Copperfield, and you've got Gump. That's immortality. – Don Noble

TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — When he learned from his dad about a neighbor's child who despite mental handicaps displayed savant behavior, University of Alabama graduate Winston Groom already was a successful journalist and novelist, but he didn't envision such a story ever becoming a pop-culture phenomenon.

Groom didn't foresee a best-selling novel that would become a movie that, 20 years after release, still plays almost continually on TV, somewhere in the world.

And he didn't foresee a movie breaking box office records, winning six Oscars and adding indelible characters and catchphrases to popular culture, spinning off a restaurant chain and inspiring adaptations around the world. That same movie he didn't see coming is inspiring a Japanese musical version even now and a possible Bollywood adaptation in the near future.

Groom just knew he had to shelve the other project he'd begun and start writing about this big galoot he'd imagined — a man with an IQ of 70 who nonetheless showed sparks of brilliance, romping through a bizarrely eventful life.

The satirical novel "Forrest Gump" — a variation on the "wise innocent" archetype, a la Huck Finn, journeying through the heyday of Paul W. "Bear" Bryant, rocketing thrills of the space race, horrors of the war in Vietnam and more — was written in an inspired six-week burst.

It starts somewhat simply, with Gump recounting problems of being treated poorly because he's "a idiot," but segues to glory days, including becoming a star Crimson Tide running back, then rolls upward to stranger, more outlandish things.

"It's a farce, and that's hard to do. The French do it well, but we don't," said Groom, in a phone interview from his Point Clear home. "If I could convince, persuasively, a reader that Coach Paul Bryant would take an idiot and put him on the football team, they'd believe anything.

"Once you hook your reader, they'll go for the rest. And that's, I think, where I hooked 'em."

After the novel hit bestseller lists, Hollywood knocked with green, as in greenbacks, fists. Groom wrote drafts of a script, but nothing seemed to happen for years, except talk, and checks that came every six months, keeping the option alive.

"I mean, every once in a while, I'd get a call: Somebody's excited, some actor or director is attached to it," he said. "I met with some of 'em; a strange and disparate group."

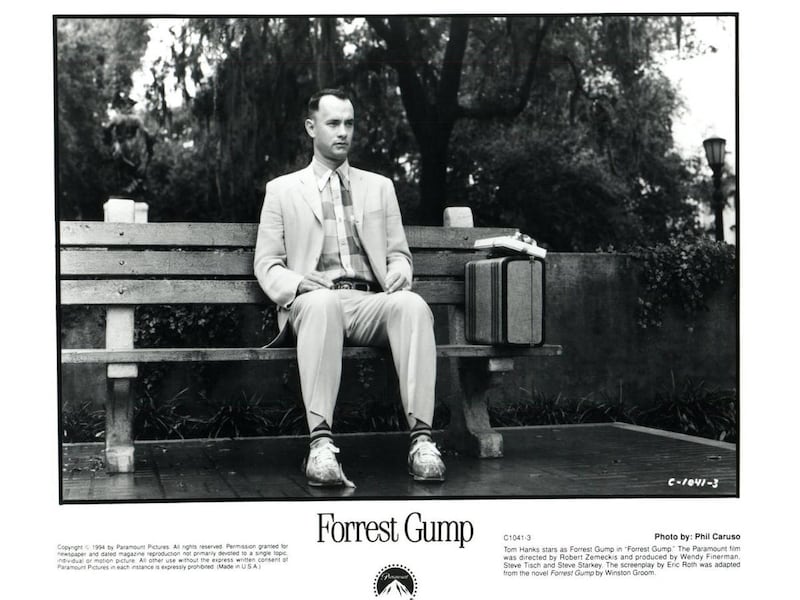

Names such as Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino were tossed about, but Groom mostly stayed apart from the process, only hearing about the project's move from Warner Bros. to Paramount from a friend, while dining at Elaine's in New York. That source also shared this news: Tom Hanks landed the lead.

"Only thing I knew about (Hanks) was he'd played some kind of transvestite in a TV series," Groom said, laughing, referring to the 1980s sitcom "Bosom Buddies," in which two single men pretend to be women to live in an affordable apartment. Groom was invited to the film's sets — nowhere in Alabama, though much of the action is ostensibly here — but politely declined.

"This wasn't my first rodeo: I've had other movies made of my books (including 'As Summers Die,' based on his 1980 novel). It's boring as hell, just the same people doing the same thing over and over again.

"Besides, it makes them nervous to have the writer around, because they know they should be ashamed of themselves."

Groom underlines that his much-discussed "rivalry" with filmmakers was highly overblown, though he enjoys joking about it. The movie did make vast changes from his novel, but as Groom sanguinely points out, the novel still stands on the shelf. And he ultimately did well financially from the film and from rights to his sequel "Gump & Co."

Yet Groom didn't really grasp how massive his 241-page story had grown until he saw a trailer on the old "Today" show.

"I said 'Now, my word; this is going to be big.' I knew how much that airtime cost," he said.

Bigger than big: It is still the fastest-grossing Paramount movie to break the $100 million, $200 million and $250 million marks, standing today at No. 31 on the list of all-time highest-grossing domestic films.

"It touched a nerve. They did an excellent job. I would have probably preferred my version of it, but that thing never would have opened," Groom said, laughing.

Hits that huge spawn other successes, including "Gump & Co.," the wit-and-wisdom collection "Gumpisms" and the 40-restaurant chain Bubba Gump Shrimp Co. with locations around the world. On Sept. 5, "Forrest Gump" will be re-released to IMAX theaters, in celebration of its 20th anniversary.

"They don't do that much anymore; I think the last one I saw was the 'Gone With the Wind' 50th anniversary," Groom said.

When Groom was honored at UA's Clarence Cason awards in 2006, Don Noble, UA English professor emeritus and host of Alabama Public Television's "Bookmark," spoke about Groom's impact.

"One of the ways that you mark the kind of immortality, or possibility of immortality of a writer, is how many characters they put into the popular culture," Noble said.

Shakespeare wins, naturally: a "Hamlet" is a ditherer; Lady Macbeth a manipulative schemer; Romeo a fatally romantic youth; Beatrice a sharp-tongued wit; and so forth. Dickens comes second, Noble said: Everyone knows what is meant by "a Scrooge." Then there's Tiny Tim, Fagin, Miss Havisham and so on.

Most writers never put a character into the popular imagination ... but Winston did," Noble said. "Gump entered the language. When you say someone is a Forrest Gump, that is a known subject. He may not be terribly smart, but he is kind and honest and compassionate. Things may go badly for a while, but he's got perseverance.

"So you've got King Lear, and David Copperfield, and you've got Gump. That's immortality."

"Forrest Gump" isn't the first book-to-movie success for an Alabama writer. There's Harper Lee's "To Kill a Mockingbird" and more contemporary works such as Fannie Flagg's "Fried Green Tomatoes" and Mark Childress's "Crazy in Alabama." ''The Hunger Games'" Suzanne Collins graduated from Birmingham's Alabama School of Fine Arts in 1980, but because her military family moved around, the state connection isn't well-known.

Born in Notasulga, Zora Neale Hurston was best known as a novelist, short story writer, playwright and essayist, but her 1937 novel "Their Eyes Were Watching God" was adapted for a popular TV movie by Oprah Winfrey in 2005. Hartselle's William Bradford Huie saw several of his books adapted for films, including "The Revolt of Mamie Stover," ''Wild River," ''The Outsider," ''The Execution of Private Slovik" (an acclaimed TV film starring the young Martin Sheen) and most notably the 1964 "The Americanization of Emily," starring Julie Andrews and James Garner, directed by Arthur Hiller with a screenplay by Paddy Chayefsky. Garner once named it his favorite of all his movies; it came out the same year Andrews became a star for "Mary Poppins."

"But even among all the Alabama novels that have gone over to the big screen and became big successes, there's still nothing like 'Gump.' It's on television in Alabama at least once a week. It's insane," Noble said.

Especially in early years after the movie came out, the Paul W. Bryant Museum got regular calls from people wanting to see Gump's records at the Capstone.

"Yeah, we've had people — not as much now obviously — we have to tell them, 'He was not a real player; he may have been based on real players, but there is no Forrest Gump in the records,'" said Ken Gaddy, director of the museum. "It's hard to convince people. They think you're hiding something."

In fact, the filmed Forrest Gump never set foot on the UA campus, or even in Alabama. The film was shot largely in the Carolinas and Georgia, with locations throughout the country for running and other scenes, and in Los Angeles.

"I remember the university didn't cooperate," Gaddy said. Many viewers were fooled by the effects that made it appear Hanks was at the "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door (Foster Auditorium)" in 1963 or played in Bryant-Denny (Stadium). UA denied filmmakers the right to use the school's name, logos or colors, though by dressing the unnamed coach in a houndstooth hat, the implication was made clear.

Historical inaccuracies from early scripts were to blame, at least in part, for UA's reluctance. One example: Gump, along with other students, was to be seen waving placards near Foster's doors, but Groom, who was at UA then, noted heavy law enforcement presence assured "You couldn't get within two miles of that place." Other references to UA and the state were not only inaccurate, but highly unflattering, he said.

"This wasn't Paramount. This wasn't Wendy Finerman's (the producer) company. ... But there was this attitude on both the West Coast, and up North that they can say practically anything about the South, and people believe it. There were just things that were over the top, way over the top," Groom said.

His concerns were brushed off, though he told the filmmakers:

"If I send this script off to (UA administrators), they're going to be distressed."

"I told them the University of Alabama is bigger than (Hollywood)," Groom said.

South Carolina won much of primary filming based on locations, including a rice field that doubled as Vietnam. Other Southern states, including the Carolinas, Louisiana and Georgia, got the jump on Alabama in offering filmmakers tax incentives as far back as the early '90s and thus have years of experienced crew to draw from. The Alabama Legislature passed its incentive bill in 2009.

"Alabama has welcomed filmmaking with open arms. We have not had any resistance at all. It's been embraced," said Kathy Faulk, manager of the Alabama Film Office.

But even if "Gump" — or a sequel — were to be shot today, Alabama would still be out of the running, because there's a $15 million cap on incentives for movies, rising to $20 million next year.

Alabama just isn't poised to land big-budget films, but can handle things like TV production, Oprah Winfrey's in-production film "Selma," John Sayles' 2007 "Honeydripper" or other independent films.

"I do think we need to increase our incentives, what we are able to give back, and the project cap," Faulk said. "To really sustain this as a viable industry, we need more.

"There are a lot of $10 million productions, then they jump to like $30 to $40 million. There are not a lot of $20 million films. I'd like to see us with a $40 or $50 million cap.

"We're not trying to compete with Georgia and Louisiana, where filmmaking is huge, but just get some of that. We want enough of a presence to employ people who want to live here and work in the industry."

Groom advocates for a stronger state-based film infrastructure, but has no dog in the hunt for a "Gump" sequel.

"What I tried to do in the sequel was have it be a lot about little Forrest, the son, and let Tom (Hanks) be the grown-up. I write books, and I think I'm pretty good at it. And (Hollywood) makes movies pretty good, too. If they make it, great; if not, I go to the bank either way.

"This thing is iconic. It's like making a sequel to 'Gone With the Wind.' The critics are going to be waiting for you. Sometimes things are better left alone. But if they do, I'll make a hell of a lot of money," he said, laughing.

Information from: The Tuscaloosa News, http://www.tuscaloosanews.com