On Dec. 29, 1845, after nine years as an independent republic, Texas was admitted to the Union as the 28th state. The delay in admittance was due to Northern fears that slavery would dominate in Texas and critically tilt the balance of power in the U.S. Congress toward the South, as well as the terms upon which Texas would enter the Union.

Mexico began its war of independence from Spain in 1810. Formally gaining its independence in 1821, Mexico was ruled by an emperor for two years before the formation of a federal republic in 1824. Part of Mexico, Texas had been luring a steady stream of American settlers, many from Tennessee, with the promise of cheap land and economic possibilities. Most of these settlers nominally swore allegiance to the Mexican constitution, but most viewed Texas' eventual annexation by the United States as only a matter of time.

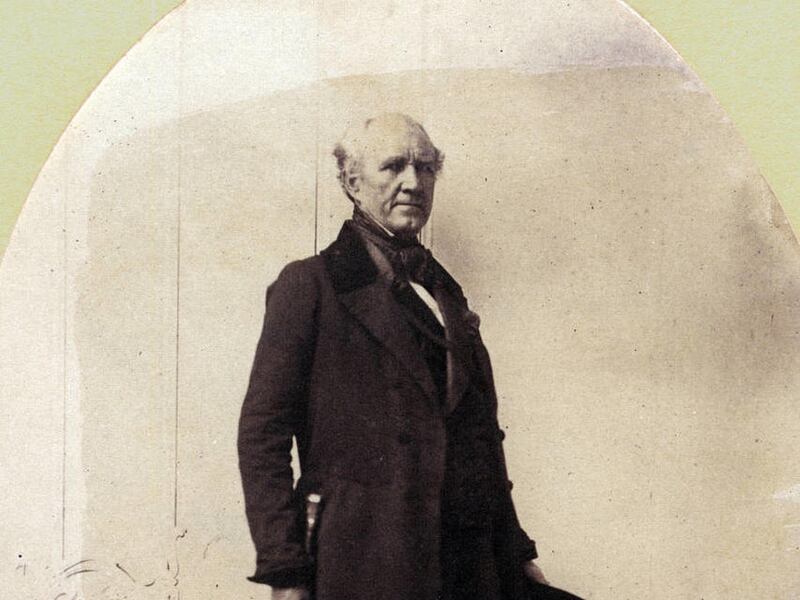

Sam Houston was one Tennessean who settled in Texas and had hopes of eventual American annexation. He was a skilled politician who for a time had served as his native state's governor. Houston, like many Texas settlers, believed that the Mexico government was limiting their rights. In October 1832, settler delegates attended a convention in which they demanded redress from the federal government, and for a time the political situation appeared to ease. Many, however, began calling for independence from Mexico.

When Mexican army officer and politician Antonio López de Santa Anna took control of the government and began ruling autocratically in 1833, many of the Texas settlers believed that he had become a dictator and that their oath to Mexico had been abrogated. In late 1835, many settlers began to actively oppose Santa Anna, and the following March, the Convention of 1836 declared Texas' independence.

At the same time, Santa Anna had moved forward to stop those he considered rebels, attacking the Alamo and massacring its defenders. The next month, Houston won a victory over Santa Anna at San Jacinto and won recognition of Texas independence. Houston was soon elected president of an independent Republic of Texas.

In the book “Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times,” biographer H. W. Brands wrote: “Houston had intended all along for Texas to become part of the United States. Most of his fellow Texans shared his desire and required only an invitation from the American government to join their political destinies to that of the country from which the great majority of them sprang.”

The fundamental problem with the Texas settlers' hope, however, was the issue that would tear the United States apart only 25 years in the future — the institution of slavery. The Compromise of 1820 had set the 36-degree, 30-foot latitude line as the demarcation between the free states of the North and the slave states of the South. Only Missouri, as part of the compromise, was allowed to maintain slavery north of the line.

At the time the new Texas Republic had undefined borders. It's northern extremity held land in present-day Wyoming, but also included territory in present-day Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Kansas. Many Northern politicians, including former U.S. president and current Whig member of Congress John Quincy Adams, feared the territory could be divided up into four or five smaller states with most of them firmly in the slave state camp.

Other problems also precluded American annexation of Texas. Crime proved to be a major problem. Lawmen could not be present everywhere in such a vast territory, and the borders, undefined as they were, could not easily be defended if a critical situation arose. Twice, Mexican armies crossed the Rio Grande and captured major settlements. American Indians remained a danger.

Finances, however, was the biggest problem faced by the new republic. Heavily in debt and with few options for increasing state revenue, Texas' money problems soon made it a laughing stock. For these reasons, Texas leaders' desire to become part of the United States went unfulfilled at the time.

Texans began to contemplate some kind of a treaty with Great Britain, which would provide the necessary trading revenue to help manage its debt, but also could theoretically assist with policing and defense of the republic. Perhaps even the weight of an alliance with Britain would be enough to check Mexico's irredentist ambitions.

Meanwhile, the issue of Texas began to become a major issue in American politics. When President William Henry Harrison died unexpectedly just 30 days into his administration in 1841, his Vice President John Tyler became the first “accidental president,” a vice president who succeeded to the presidency through a president's death. Tyler soon estranged himself from the Whig party because of his stand on the Bank of the United States issue. Whig leader Henry Clay vowed revenge and soon became Tyler's principal political enemy.

At this time, Texas became intertwined with another major issue involving American expansionism — the Oregon Territory, which had been ruled jointly by the United States and Britain for more than 20 years. While Britain insisted on the bulk of the territory for itself, the United States did the same. Just as most Southerners wanted Texas annexed, Northerners wanted statehood for the Oregon territory. Now, many in the United States feared that Britain would attempt a land grab in Oregon even as it diplomatically drew closer to Texas. Something had to be done.

The presidential election of 1844 brought these issues to the foreground. The Whigs nominated Clay for president and the Democrats selected the choice of former President Andrew Jackson — fellow Tennessean James K. Polk. Both candidates were asked their position on Texas. Should the United States annex the republic? Many Northerners began to become less hostile on the issue, especially if it meant that Oregon would soon follow.

Polk was for Texas annexation, which was expected from the typically pro-expansionist Democrats, (though it had been Democratic President Martin Van Buren who had rejected Houston's initial offer of annexation in 1837). He also favored annexing the whole of the Oregon territory. With much of their support from abolitionists in New England, the Whigs typically opposed expansionist adventures, particularly those that could create more slave states. Clay, however, tried to have it both ways.

Clay, a slave owner from Kentucky who had unsuccessfully run for president three times before, officially stated that the annexation of Texas could threaten the stability of the republic by creating another crisis centered around slavery. He did, however, write private letters intended for public consumption that stated that he would be willing to support Texas annexation, if the country wanted it.

A man without a party, sitting president Tyler also favored Texas annexation. At one time, Tyler and his secretary of state, John C. Calhoun, even contemplated offering a three-way deal that would give Britain much, but not all of Oregon in exchange for cash payments to Mexico. The Mexicans in turn would hand over a portion of northern California to the United States. Texas, thus surrounded by the U.S. on three sides, would naturally be annexed. Such schemes, however, came to nothing.

After Polk's election in November, Tyler addressed Congress the next month, and stated that “A controlling majority of the people and a large majority of the states have declared in favor of immediate annexation.” He then asked Congress to pass a joint resolution, forgoing the usual necessity of a two-thirds mandate in the Senate for an annexation treaty and the almost certain battle with Clay's Whigs. Congress began a new round of debates on the issue that brought up still unresolved problems like Texas' debt and borders. Also, many asked if such a joint resolution was constitutional?

Milton Brown, a Whig from Tennessee, offered a compromise that would allow for annexation, with Texas' borders to be defined after annexation. The United States would not assume Texas' debt, but neither would it appropriate Texas' vast lands. These lands could be sold to pay off the debt. Importantly, Texas would be admitted to the Union as a state, not a territory. It would be admitted as a slave state, though some of its northern territories could be carved into free states at some later time.

In early March 1845, after significant amendments and additions by other congressmen such as Thomas Hart Benton, and with the full support of Tyler and President-elect Polk, Texas was informed that the United States was ready for annexation. Upon Polk's inauguration, he also sent assurances that the United States would defend Texas in the event of a Mexican attack, an advantage that Calhoun had teased Texans with for months.

The Texans had been doing some teasing of their own. Though no longer president, Houston remained the man to impress in Texas, and he had threatened, as subtly as possible, that Texas would draw closer economic ties to Britain, if the United States didn't act fast.

At a special session of the Texas Congress, the new Texas President Anson Jones offered two documents for the body to consider: a resolution allowing Texas to be annexed by the United States, and a treaty with Mexico, brokered by Britain, guaranteeing Texas' still-undefined borders with Mexico if Texas refused annexation. Though many Texans hoped that the United States could eventually be talked into assuming Texas' debt, most recognized that the time was right. The treaty with Mexico was thrown out and the resolution for annexation was adopted, both unanimously.

In the book, “Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America,” biographer Walter R. Borneman wrote: “On July 4, the special session ratified both the acceptance of statehood and the state constitution. All that remained was the perfunctory ratification by popular vote in October. Once the outcome of this vote and the state constitution were transmitted to the U.S. Congress, a final resolution was passed admitting Texas to the Union as the 28th state. President Polk signed it on December 29, 1845, and Texas was finally and officially a part of the United States.”

Texas formally submitted to United States sovereignty in February 1846.

Cody K. Carlson holds a master's in history from the University of Utah and teaches at Salt Lake Community College. An avid player of board games, he blogs at thediscriminatinggamer.com. Email: ckcarlson76@gmail.com