When I was in the third grade in Jackson, Miss., in 1963, I won a citywide essay contest. The award made me very happy. The essay topic was “Helping Others” and my conclusion said: “Just because of the way they look or talk doesn’t mean that they’re bad. You should not play with just some people. You should make them all your friends.”

To announce the award, the school board sent out a letter saying that mine was being honored as the best third-grade essay that semester from “Jackson’s white schools.” Full of pride regarding my insights on the importance of “making them all your friends,” I hardly noticed the irony.

This story nicely illustrates the phenomenon of selective empathy. The word “empathy” came into the English language in the early 20th century as a translation of the German word “Einfuhlung,” which means “feeling into.” The word began largely as an aesthetic term, as philosophers struggled to explain why works of art, or scenes of nature, can move us emotionally. If you’ve seen the new movie “Mr. Turner,” about the great British Romanticist painter J. M.W. Turner, you know that Turner had astonishing empathy for — he “felt into” — the qualities of sunlight and landscape and was able, through his painting, to help us “feel into” them as well.

Today we typically use the word “empathy” to mean the capacity to identify deeply and emotionally with another person’s situation and feelings. Discussing the related concept of sympathy in 1759, the great economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith wrote that “it is by changing places in fancy with the sufferer, that we come either to conceive or be affected by what he feels.” That’s a lovely definition of empathy. Scholars seeking to understand the qualities of wisdom consistently report that empathy — putting myself sincerely in the other person’s shoes — is a key pathway to wisdom.

Selective empathy is when children and teachers in 1963 can admirably encourage empathy for others — “You should make them all your friends” — so long as the definition of “all” is restricted to “Jackson’s white schools.”

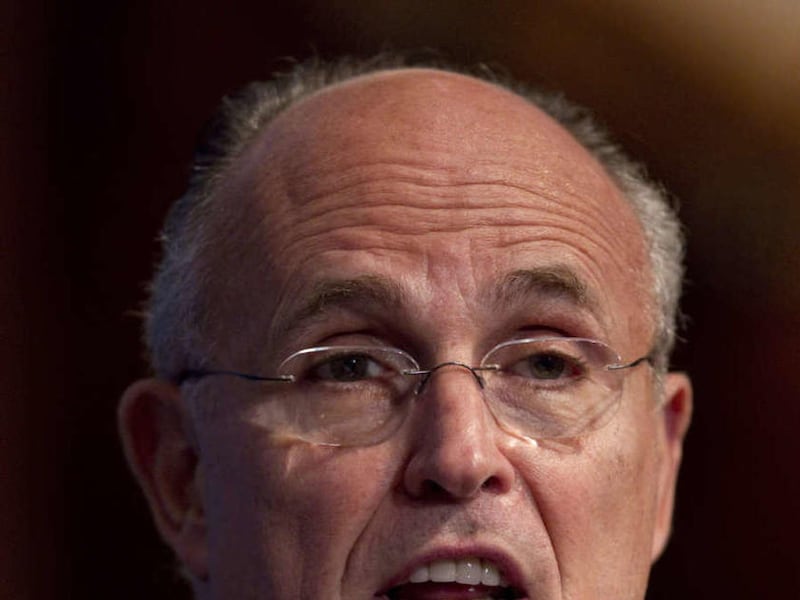

Recently, responding to marches in New York and elsewhere focusing on what is viewed by the protesters as police brutality against African-Americans, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani went on TV to say flatly that “the police aren’t racists” and to insist that the problem is not the police, but the people who won’t support the police. Giuliani was far from alone in expressing this view.

Much of this perspective stems from genuine, admirable empathy. Giuliani and many of us can “feel into” the situation of the police. We understand that so much of their work is tough and demanding. Working on the front lines, they risk their safety every day to try to keep us safe. The jobs are more blue-collar than upscale. We may not pay these people what they deserve, but at least we owe them our respect and gratitude.

I agree with this way of thinking, but I mistrust the selective empathy that seems often to accompany it. In what ways does our common humanity also call us to “feel into” the situation and feelings of African-Americans — in particular young black men — in poor communities? Can we as a society walk in their shoes as well? Or should most of us continue to treat their repeatedly stated conviction that police brutality exists as simply a false idea that is best ignored or denounced?

Of course, on this issue selective empathy can work the other way, too. Especially if I’m willing to switch back and forth between, say, Fox and MSNBC, for nearly every talking head I find on TV empathizing with the police and stereotyping the protesters, I can find another doing the exact opposite.

What’s rarer, and surely more needed, is a capacious empathy that “feels into” the actual situations of both those I can readily recognize and those I can less readily recognize. Absent that (admittedly difficult) non-selective empathy, we can certainly have a fierce debate, but we’re unlikely as a society to produce much wisdom.

What feeds today’s ugly hyper-partisanship? There are many sources, but an important one is the belief that society is divided into two mutually incompatible groups — the group of me and those like me who stand for truth and justice, and those not like me who stand for the opposite. Notwithstanding its current popularity, this is a deeply wrong-headed way of seeing the world. Perhaps the most powerful antidote for it is empathy.

David Blankenhorn is president of the Institute for American Values. You can follow him on Twitter @Blankenhorn3.