When I got discharged from World War II, I felt cheated cause I didn’t get to write a page of Marine history, but I did get to help write a page in North Korea. – John Cole

ROY — It has been more than six decades since John Cole survived the cold and bloody hand-to-hand combat on North Korea’s legendary Chosin Reservoir battlefield, and he can still feel it in his bones. When the weather turns, the ache in his hands, hips, knees and feet returns, reminders of the weeks he spent trying to fend off frostbite and Chinese soldiers.

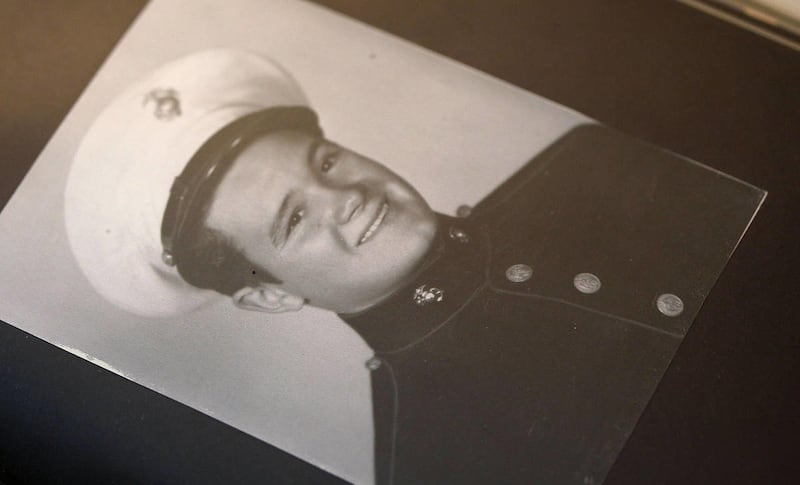

The years have only made it worse. He’ll turn 88 this spring, and the old soldier is wearing out. He’s got a mechanical knee, a mechanical hip and a mechanical gizmo in his heart. He walks slowly and haltingly. Thin and white-haired, he doesn’t look like a man who once stabbed an enemy attacker in the heart and survived three wounds during the battle. There is little about him to suggest all that. Well, except for this: The flagpole next to his double-wide trailer home in Roy flies a Marine Corps flag. He wears dog tags over a Marine Corps T-shirt, tucked into a belt that holds a Purple Heart buckle and a cellphone carrier that sports a silver Corps emblem, and when the phone rings it plays "The Marines' Hymn," and the voice mail announces, “I’m either fighting another battle or sleeping on the side of the road.”

In his family room there is a razor-sharp KA-BAR knife he wore in the Marines and a wall covered with certificates, medals and photos, which stare down on a wooden box filled with souvenirs marked “Semper Fi.”

Cole rolls up his right sleeve to show a guest the one souvenir he carries with him always — a jagged scar where a bullet entered one side of his forearm and exited the other.

He has never really left the Marines behind even though his wounds forced him to take a medical discharge in 1952. He joined an organization that was formed by Chosin survivors called The Chosin Few. He shows a guest a copy of the group's charter, which reads:

“Whatever we were in that frozen long ago and whatever we are now, we are bound as one for life in an exclusive fraternity of honor. The only way into our ranks is to have paid the dues of duty, sacrifice and valor by being there. The cost of joining, in short, is beyond all earthly wealth.”

There are a few battles that define the Marine Corps. Among them: Belleau Woods, Iwo Jima, Guadalcanal, Tarawa and Chosin Reservoir. The latter is the least known, perhaps because Korea never carried the cachet of a world war. It has been largely overlooked and forgotten. The story was finally told, 60 years later, in a documentary film in 2010.

The battle lasted about 2½ weeks, from late November to mid-December. The 1st Marine Division — along with the U.S. Army and United Nations forces — crossed the 38th parallel into communist North Korea hoping to beat the enemy to the Yalu River — considered a strategic stronghold — in what was expected to be the final campaign to defeat the faltering North Korean Army. Two things stymied them: the weather and the Chinese.

Temperatures never got above minus-30 degrees, with winds that reached 69 miles per hour. It was difficult enough just trying to endure the cold, but meanwhile the 25,000 U.N. forces — U.S. Marines, U.S. Army and British Marines — found themselves surrounded by an estimated 120,000 Chinese soldiers at a high-mountain reservoir called Chosin. The Chinese had launched a surprise offensive to support North Korea.

Cole was on the front lines. He had come to Utah at age 15 when his father found work at Hill Field (now Hill Air Force Base). He took a summer job himself at Hill, fully expecting to enroll in high school in the fall, but the Great Depression was still in its late stages and his family needed the extra income to pay for medical expenses for an ailing sister. He never returned to school. He worked on the base for a couple of years and then enlisted in the Marines at age 17 because, as he puts it, three meals a day and a place to sleep were better than selling apples on the street corner. He trained in California for an invasion of Japan, but the U.S. dropped a pair of nuclear bombs instead and that was that.

“I felt bad because I didn’t get to help write a page in the history of the Marines,” Cole says.

After he was discharged, Cole returned to Utah, married and started a family — he and Donna would have four sons. He took a job making tents and awnings in Salt Lake City, and continued to serve in the Marine Corps Reserves. When the Korean War heated up, Cole was among the first to be activated and sent to war. His war would last only three weeks.

Cpl. John Cole arrived in Korea with the 1st Marine Division in late November. They made their way north by foot, trucks, bus and train. They lived for weeks in foxholes they dug in the frozen ground and struggled to stay warm (they couldn’t build fires, which would give away their position). Cole recalls temperatures as cold as minus-50 degrees, which didn’t even consider the icy wind coming down out of Manchuria. Cole was wearing thermal underwear, dungarees, a canvas pair of outer pants, a long-sleeved thermal T-shirt, a sweatshirt, a jacket, a field jacket and a parka.

“And I was cold all the time,” he recalls.

Bullets took their toll, but so did the cold. In his book, "McArthur's X Corps in Korea/Inchon to the Yalu 1950," Edward Daily recounts a scene in which a Chinese officer "was puzzled by (the sight of) snowmen dotting the bleak landscape. Who would build snowmen in pairs and clusters in such a forbidding place? Then he realized they were his own soldiers, thousands of them. Entire platoons perished in place. Lifeless soldiers sheathed in snow, squatted with rifles on their shoulders and kitbags on their backs on this ghostly freezing ground."

Once they reached Chosin Reservoir, Cole’s four-man fire team was sent on a recon mission deeper behind enemy lines with orders to return before dark. “We saw lots of footprints everywhere, not just on the road,” he recalls. “It got so we felt there were eyes watching us.” They found a wounded enemy soldier in an abandoned building and carried him back to headquarters on an old door they ripped off the hinges. The Marine interpreter said he was Chinese.

On the night of Nov. 27, the Marines were dug in trying to sleep while also keeping watch for the enemy. That night they heard noises in the trees. Standing up in his sleeping bag to see what he could see, Cole eventually drifted to sleep, but when he opened his eyes again he thought he saw solders in the dark. After studying the landscape further he was convinced that the enemy was out there and moving. Flares were fired into the night sky over a rice paddy. All hell broke loose.

“Most of the rice paddy got up and ran at us,” says Cole.

Tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers attacked the Americans at various places around the reservoir, unleashing a cacophony of cowbells, air horns and screaming. Up and down the line the Marines opened fire, but many of them discovered that the bolt actions on their rifles were frozen and couldn’t eject the shells. “They kicked their rifles and urinated on them to thaw the action,” says Cole. After the rifles were fired a few times they warmed up and worked properly. The fighting went on all night, as the Chinese swarmed the American perimeters, coming within yards of their positions.

“We saw lots of dead the next morning,” recalls Cole.

This would be the pattern for the next two weeks, with the Chinese attacking at night. A couple of days later U.S. forces turned southeast to head to the sea where they could be protected and picked up by the Navy, but getting there was deadly. Night after night, the Americans took a series of hills as they worked their way through the enemy, with the Chinese coming out from hiding in the darkness to attack.

“We got the final rites from the chaplain three different days,” says Cole. “We weren’t supposed to survive the next hill. We were way outnumbered.”

On the side of Hill 1520, Cole posted his team behind rocks. A grenade explosion knocked him off the hill, ripping into his thigh and back. He tumbled down the hill until he slammed into a rock. Cole climbed back up to his position with blood pouring out of his thigh, but there was no time to treat it now. He had run out of clips of ammunition and was trying to load individual rounds when the Chinese attacked with fixed bayonets in the middle of the night. Cole looked up just in time to see a Chinese soldier bearing down on him with a knife in his hand.

“I grabbed his arm and hit him in the throat with a clip because I hadn’t loaded my rifle,” he says. “He bled all over me before I could move him out of the way. I started loading again and here came another guy and I stabbed him in the heart with my KA-BAR. And then came another guy with a bayonet. I knocked his bayonet to the side just as he pulled the trigger and it blew out the back of my forearm. Then I cut his throat with the KA-BAR. I went into shock. My tongue swelled up and I couldn’t talk. I thought I was going to die. I couldn’t move my right arm. We had all run out of ammunition and most of us were wounded. All the corpsman could do was wrap my arm.”

Cole made his way off the hill back to safety and his war was over. If it had been summertime, he believes he would have bled to death, but the freezing temperatures stanched the bleeding. “I should have been dead a dozen times,” he says.

He spent 20 days in a hospital in Japan and more than a year in a hospital in the States recovering from his wounds, which required a few surgeries to repair. When he first came off the battlefield, nurses discovered that his socks were frozen to the bottom of his feet – they pulled off skin as they peeled them off. He had frostbite on his knees, hands, ears, feet and parts of his face. He had hoped to make a career of the Marines, but the wounds precluded such hopes. For months it was difficult for him to walk.

The U.S./U.N. did not win the battle — Time Magazine called it the worst defeat the U.S. had ever suffered — but others considered it a victory that the Marines were able to escape overwhelming, surrounding forces while inflicting heavy casualties on the Chinese. According to Daily, of the 25,000 U.S./U.N. troops, 6,000 were killed, wounded or captured, and 6,000 suffered frostbite. The Chinese casualties: 25,000 dead, 12,500 wounded, 30,000 frostbitten.

“When I got discharged from World War II, I felt cheated cause I didn’t get to write a page of Marine history,” says Cole, “but I did get to help write a page in North Korea.”

He said this as he sat in his home while a cold January rain fell outside. Two days later he left town, making his annual migration to Southern California. The warm weather provides relief from the old frostbite that flares up, another reminder of that long ago battle.

Email: drob@deseretnews.com