In less than a second, the sun makes as much energy as the United States uses in one year.

That scientific tidbit wasn’t broadcast to the public through a science documentary or high-brow academic study, but through physicist Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Twitter feed, which currently boasts more than 3 million followers.

Tyson’s Twitter feed or astronaut Chris Hadfield’s YouTube videos from the International Space Station are examples of how the Internet has changed the way society talks about science. Hadfield’s parody video of Davie Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” for example, had more than 24 million hits in 2013.

“Scientists have new platforms to engage the public that didn’t exist a few decades ago,” said Cary Funk, a co-author of a series of new Pew Research Center studies looking at science and society. “That’s allowing younger scientists who see this as an avenue to get the word out about their work.”

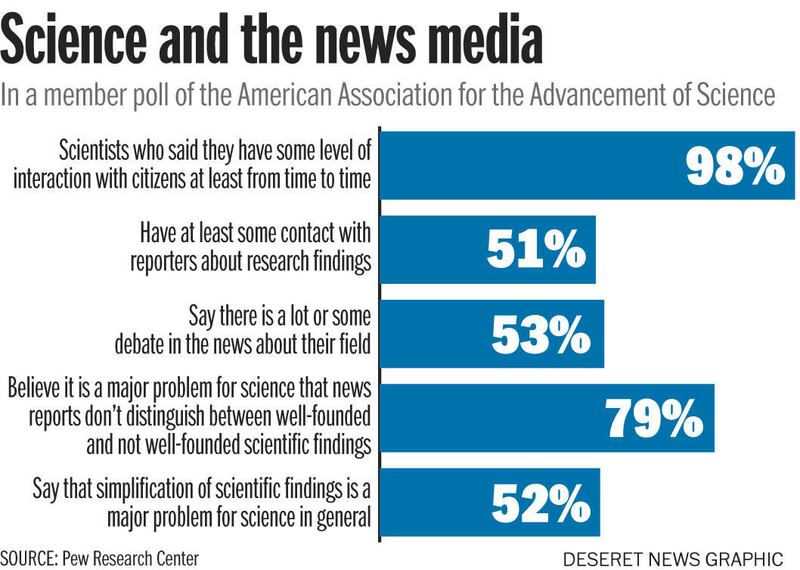

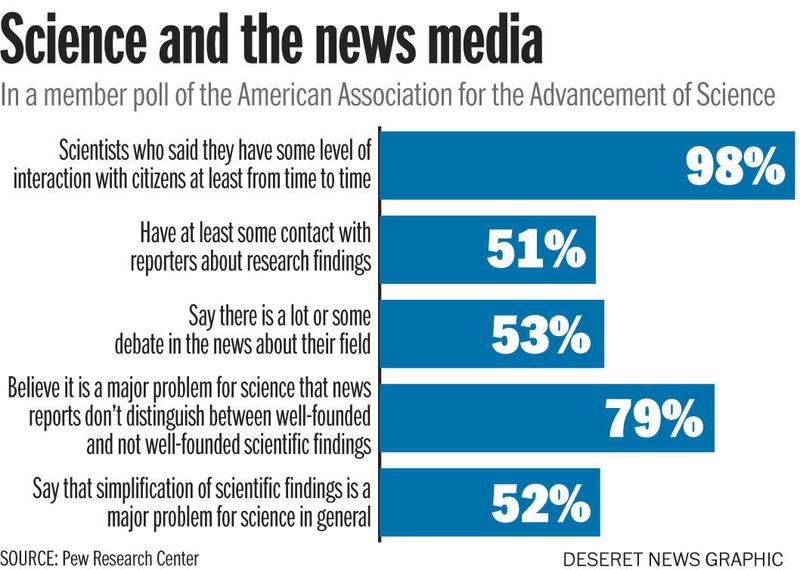

Pew’s most recent report in the series surveyed more than 3,000 members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a nonprofit group made up of scientists and science advocates.

The response found that 79 percent believe the media can pose problems for science when all studies — whether “well-founded” or not — are reported without addressing caveats like methodology for the study. Fifty-two percent reported concern that “simplification” of scientific findings is a problem for science. That’s good and bad, says Penn State research ethicist Brad Woods, because while the Internet has surely made science more accessible to the average person, not everything online is carefully vetted.

“When information gets out there to the public, it helps science for the better,” Woods said. “But it used to be that you had to establish yourself as a scientist. Now, that’s not so much. If you have a critical mind and write well, you might be able to sway public opinion.”

Engaging the public

Learning one of Tyson’s facts or marveling at Hadfield playing guitar in zero-gravity have positive side effects aside from being interesting — it makes science careers seem cool at a time when science needs the public to care.

The end of NASA’s space shuttle program in 2011 prompted fears about America’s declining foothold in space travel and technology development, as the New York Times reported. “NASA has been forced to cancel the big missions that capture public attention and attract top talent,” William J. Broad wrote. “There is little glory to look forward to.”

That makes scientists engaging the public — especially young people — more important than ever, University of Wisconsin-Madison Life Sciences Communication professor Dominique Brossard says.

“By not communicating interesting things about science and making people realize importance of scientific development, you run the risk of people not engaging in those careers, which we need for the betterment of society,” Brossard said.

But science’s online relationship with the public has some drawbacks. Misinformation has a long online lifespan, Brossard says, and debate over faulty studies can make the Internet a polarizing place. The Pew study found that 53 percent of AAAS members saw "debate" around science in their field in the public.

“Science might be more visible online, but because of the way Google works, it might not be the science we want,” Brossard said. “Even if a study has been retracted, it’s going to show up in search results.”

One example is the recent debate over childhood vaccinations. Although the original 1998 study that linked vaccination to autism in children was retracted and the author accused of fraud in 2011, many continue to debate whether or not the MMR vaccine contributes to autism in children. Celebrity parents coming out against vaccination hasn’t helped, Woods said.

“I think by and large the public trusts science,” Woods said. “But I think people are drawn to celebrity more than science.”

Bucking tradition

While scientific progress used to be confined to journals, Woods says the Internet is also bucking science publication traditions — with social media and elsewhere online.

“There’s a saying among scientific researchers: Publish or perish,” Woods said. “If it’s not published, it’s not science.”

The Pew report found that many scientists use social media and the Internet to reach out to the public — almost half those polled reported that they used social media to discuss science and research.

Scientific publishing is a billion-dollar industry. English language journals reported an annual revenue of $9.4 billion in 2011.

“There were 1.8 million English articles in 2011,” Woods said. “That’s a lot of science coming out.”

While many journals make their content available online, most employ subscription paywalls that have become the targets of some high-profile hackers in recent years.

Most notably, Reddit cofounder Aaron Swartz hacked millions of articles from online database JSTOR in 2011. After the U.S. Attorney’s Office would not offer Swartz a plea deal once the articles were returned, JSTOR released the articles Swartz hacked to the public in solidarity.

Swartz later committed suicide, which Woods said helped galvanize the movement for copyright reform and open access of scientific journals.

“It’s clear there’s public outcry for access to this information,” Woods said. “I think the Internet has changed the way publication is going to work. The undercutting of that would be far-reaching but difficult to define — from employment to tradition.”

Whatever the future holds for science’s place online, Woods says it’s important to remember the opportunities it’s given to science and society.

“Before the Internet, a scientist could only disseminate their work through professional conferences or journals, but now they can log on and give back their research,” Woods said. “These are growing pains — there’s no clear-cut path, but any time info gets out there, it’s for the betterment of science.”

Email: chjohnson@deseretnews.com

Twitter: ChandraMJohnson