SALT LAKE CITY — State education leaders aren't satisfied with Utah's place in the middle of the academic pack, and the road to becoming a national leader, they say, is one of "urgency, apprehension and hope."

Right now, 84 percent of high schoolers in the state say they are college-bound, but only one in four of them scored proficiently in all four areas of the ACT, a national college-readiness exam administered to Utah's high school juniors.

More than one in four students are reading below grade level in first, second and third grades — a time and metric that together are "perhaps the single most critical marker of any in education," according to Brad Smith, state superintendent of public instruction.

"I look at our performance and I know that we are not serving the needs of students the way we should," Smith told the combined editorial board for the Deseret News and KSL. "It's just that simple."

But top educators hope a strategic K-12 education plan being developed over the summer will raise expectations for student performance, strengthen instruction and school leadership, and articulate the priorities in funding a student population that grows by 8,000 children each year.

"We need to have a plan to advance from mediocre to top-tier. We need to articulate what the plan is, then price it out, then ask for the money," Smith said. "Before we want to ask the taxpayers of Utah to make an investment, we've got to articulate what's the prospectus.

"Because frankly," he said, "the danger is if we do what we did this year, which is a substantial payment into the weighted pupil unit — and I know this will cause some feathers to be ruffled — that is simply paying more and making a bet that the same system will deliver something different."

The Utah State Board of Education will ultimately decide what Utah's strategic plan for public education will look like by Labor Day, it's target completion date. Much of the plan will deal with accommodating more students, which are expected to reach 1 million by 2050.

"We know we're going to have to increase the capacity of our education system because the number of students continues to increase," said David Crandall, chairman of the State School Board. "At the same time, we want to make sure that we are improving the quality of the system as well as paying attention to the equity or the fairness overall, both in funding models and in delivery."

But if new money isn't the only catalyst for school improvement, what else has to change?

Smith said he is pushing for a stronger focus in three areas, which he said will lead to a discussion about effective placement of education dollars: changing instruction, data-driven teaching and school leadership.

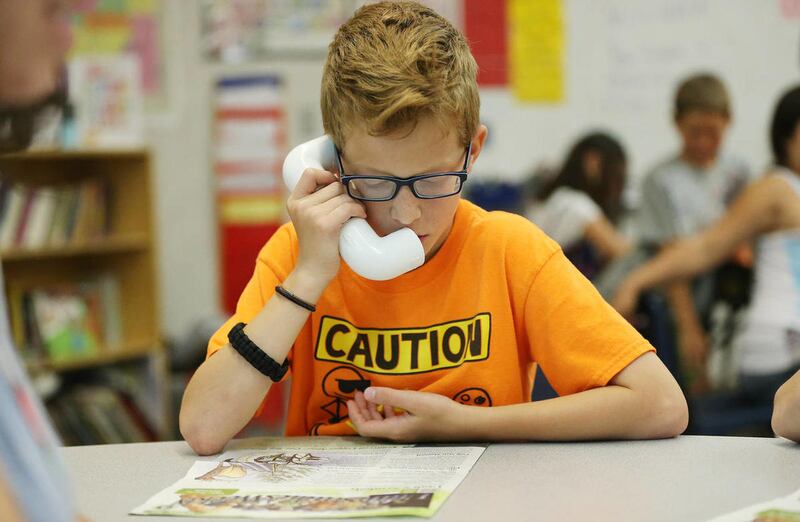

In the classroom

This year, the Legislature granted a 4 percent increase to the weighted pupil unit, Utah's formula for flexible school funding. While Smith agrees with other educators that the increase was appreciated, he said a more targeted funding approach is needed to move the needle in key academic areas, such as K-3 reading improvement.

Most years, Diamond Ridge Elementary starts out with roughly 70 percent of first-, second- and third-graders reading on grade level, just ahead of the statewide starting average of 66 percent.

But by the end of the school year in 2014, the West Valley school had almost 97 percent of its third-graders reading at or above grade level, well beyond the year-end state average of 74 percent.

That occurs even though Diamond Ridge is part of one of the largest and most diverse school districts in the state.

Part of the school's success is tied to a robust intervention program that identifies early the students who need extra help and gives them more time with a teacher, according to principal Debbie Koji.

"Obviously, your first level of attack for reading is in the classroom. Good solid reading instruction is what you want first," Koji said. "I think it's critical that we catch these kids so that they don't fall further behind. … If you're struggling on something, you need more time, you need more focus, you need more intensity. Those are the pieces you've got to have to learn anything."

The intervention program requires flexibility among teachers and administrators. Teachers rotate taking on additional students during independent reading time to allow other teachers to meet with students who are falling behind.

Smith said having teachers and school leaders who are flexible and willing to innovate to find the most effective practices for their students are central to a necessary shift in instruction.

"To me, one of the things is shaking some people in the educational establishment out of their torpor. There are things that are engrained that have to be changed," Smith said. "We have to talk about the fact that we have an educational crisis in Utah."

Reading on grade level by the end of third grade is "absolutely critical" to a student's long-term success, Smith said, but it's unclear whether lawmakers fully agree. As part of a budgeting exercise, legislators this year proposed cutting $2.6 million from the K-3 reading improvement fund, though the appropriation ended up unchanged at $15.3 million.

The annual appropriation for K-3 reading hasn't increased in the better part of a decade, despite inflation and increased enrollment.

"I would suggest maybe we ought to put $50 million into that," Smith said. "That would be a place to make a very small bet in the grand scheme of things that has the potential of paying off huge."

Math is an investment of similar worth, the superintendent said, though it's an area where fewer students are considered proficient and where the gap among minority and low-income students becomes more visible. Last year, only 39 percent of students scored proficiently in math on SAGE, Utah's year-end assessment.

Often, Smith said, educators and state leaders grow accustomed to lower math scores, with what he calls an "easy acceptance of lesser expectation." But students' ability to perform in math is becoming more critical in an evolving post-college landscape, he said.

"If I looked at you and said, 'Only one in four kids can read,' we would all say that's a horrible thing. If I say the same thing about math, we all laugh and say, 'That's why I went to law school, so I didn't have to do math,'" he said. "Being numerate is at least as important" as being literate.

Checkup vs. autopsy

This month, most schools completed for a second time the computerized test known as SAGE, which stands for student assessment of growth and excellence. Teachers and administrators hope this year's data contrasted with last year's will uncover trends that show student growth across the state.

Last year, SAGE data didn't become available until well into the following school year, months after the test was completed. Parents and school leaders this year are expected to be able to see the results much sooner, but the once-a-year snapshot of student performance only goes so far in the classroom, Smith said.

"They need checkup data, not autopsy data," Smith said. "So having a system in place in every (school) that allows for short-cycle formative assessments that allow teachers to have instantaneous feedback and make adjustments is a critical change that we can make across the state."

Koji said data collected through more frequent assessments provides confirming guidance for teachers as they work with students one-on-one. Test results can also encourage pupils who want to see how their work pays off, she said.

"You've got to know what you feel," Koji said. "Data is critical. That being said, data can only guide your instruction. What I do at the beginning is what's going to impact that data on the other end."

Periodic assessments, such as a formative form of SAGE, are used in various schools and will be part of the board's plan to encourage data-driven instruction in the classroom, forming part of a comprehensive accountability system, according to Crandall of the state school board.

"SAGE can only be one part of any accountability system for the simple fact that it doesn't test all of the subjects," Crandall said. "In fact, it doesn't even test the majority of the subjects that are taught in school, and we do want an accountability system that extends beyond that in areas that currently aren't assessed."

Just as important as the ability to gather data is the interpretation of it, according to Tami Pyfer, education adviser to Gov. Gary Herbert. Currently, lawmakers use data from SAGE in two accountability systems.

Utah's school grading system assigns a letter grade to each school based on SAGE results, ACT scores and graduation rates. The governor's PACE report card, Utah's less-controversial accountability system, includes SAGE scores, literacy rates, school demographics and performance within those demographics.

"Our goal was to provide information that parents really could use," Pyfer said of the PACE report card. "We're trying to provide more information so that parents really could have a choice, and it provides this measure of accountability for the general public."

Regardless of whatever formative assessment system schools use, or what accountability system parents choose to consider, the data is only useful if it leads to student improvement, Smith said.

"There is no magic in a particular system. It is in the use of the information to change practice that is critical. As such, it is cultural change, not programmatic change, that is called for," he said. "To me, the measure is what happens with students. Ultimately at the end of the day, that has to be the ultimate test: Are students learning?"

Management or leadership?

Utah's plan for education will likely revisit how school leaders facilitate the success of their teachers and students. While Utah only spends 6.8 percent of its per-pupil funds on administration, more is being asked of school principals as academic standards change and student populations grow and diversify.

Sometimes, the vision of instructional leadership gets blurred in the process, according to Smith.

"We need to get out of the business of having managers and get into the business of having leaders, that being really fundamentally changing our view of what the principal does," he said. "It's not making sure that school lunch is served and that the lights are on. It's about being an instructional leader, working in partnership with the teacher, having a meaningful observation and feedback cycle."

Jacob Hunt is the principal at Lincoln Academy. Last year, the Pleasant Grove charter school had 94 percent of its first- through third-graders reading at grade level, even though many of the school's students qualify for Title I assistance.

Hunt said teacher observations are frequent as he strives to help teachers do their best.

"For me personally, I feel that my job is to hire amazing teachers and then get out of their way and provide as much support as they need," Hunt said. "However, to be present enough to know that if something is going wrong, I need to get in the way and I need to provide guidance."

Smith said state and education leaders should also think more broadly about finding capable leaders for schools. That includes opening on-ramps to administration for people from non-educational backgrounds who have "transferable skills," he said.

This year, the Legislature passed a bill that would have allowed schools to hire individuals who don't hold a teaching license or a graduate degree in an area of education. But the governor vetoed the bill, saying such a decision should be up to the State School Board.

The board is expected to discuss licensing of educators and administrators in its monthly meeting this week.

Crandall said school and district administrators will also play key leadership roles as the state considers competency-based models for teacher compensation, which could be the subject of future legislation and State School Board planning.

"Funding is always going to be an issue, so we always need to make sure we're getting the biggest bang for whatever buck we have available to us," Crandall said.

Changing perceptions

Pyfer said what often prevails is a "false narrative" about the quality of Utah's teachers. But instead of focusing on the flaws of educators, she said, state leaders should provide better incentives for success in the classroom.

"We've got great teachers, but we're losing great teachers," she said. "For me, the narrative shouldn't be how bad our teachers are, it should be how do we keep these great teachers that we're attracting from going into different fields."

Beyond changes to instruction, data use and leadership, Smith said believing Utah can change its academic outcomes has to become the modus operandi for educators.

At a Utah Taxpayers Association last month, Smith spoke of faith as "the single most important change in public education."

While faith in students and teachers isn't something that can be implemented through board rule, it's needed to overcome the "institutional belief" about which groups of students can and can't succeed, he said.

Prior to his appointment at the Utah State Office of Education, Smith was a board member and superintendent of the Ogden School District, which has one of the highest rates of impoverished students in the state.

Historically, Ogden had six of the 10 lowest-performing schools in Utah, but the district quickly became known as a leader in academic turnaround programs through administrative changes and a data-driven approach to teaching.

Dee Elementary, for example, more than doubled its proficiency scores in language arts between 2010 and 2013.

The same can apply for Utah as a whole as it innovates, plans and works its way to the front of the academic pack, Smith said.

"What we also observed in Ogden and what I believe has shown across this country and the world, as the expectation rises for these kids who have often had a poverty of expectation, it lifts the boat for all kids," he said. "All of a sudden, the expectation is we all perform at high levels."

Email: mjacobsen@deseretnews.com

Twitter: MorganEJacobsen