It's midmorning, but the Cottonwood Heights, Utah, basement apartment of Frank Herrmann is still dark.

His 6-foot-4 frame sprawls out from under the small table, the remains of his Eggo waffles and fruit breakfast forgotten in front of him. He holds his iPhone up to his face, smiling down at his wife and young son who are in Goodyear, Arizona, 700 miles away. Herrmann sputters his lips, imitating a horse, at the phone, and his 14-month-old son Franco does it right back.

The 31-year-old father laughs and rubs the light brown hair of his receding hairline, where more often than not a ball cap is perched. Herrmann glances around his small, bare-walled, bachelor-like apartment and wishes he were in Goodyear. This is the life of a professional athlete few ever see.

The family Facetime goes on for a few more minutes before Frank checks his watch, which is set to Arizona time. It's time to go. They wave their goodbyes, promising more texts and phone calls throughout the day.

Herrmann grabs his Bees ball cap and sunglasses and heads to the minor league baseball diamond in downtown Salt Lake City.

Herrmann is a relief pitcher for the Salt Lake Bees, husband and father. His wife is pregnant with their second, a daughter, Lola. With an economics degree from Harvard, Herrmann could have a completely different life. These days it's a life of two rental payments, frequent flier miles and constantly planning for the next trip home. This version of fatherhood isn't exactly what Herrmann expected when he started this baseball journey back in 2006, but now that he has it, he wouldn't give it up.

"My favorite thing about being a father is the little things you see every day and take for granted, every little thing they do, every milestone they hit. … You see those things all the time with other people's kids, but you don't really get it till you have a kid of your own."

Major decisions

From the stadium seats looking in on the infield, it's easy to see baseball as a brightly lit, glamorous game; a chance to peer in on a world where grand slam successes are met with roaring applause and Little League dreams become major realities.

What is often forgotten is that the path to Major League Baseball stardom isn’t just a game. It’s also the career choice of hundreds of hardworking fathers. And not every dad makes it to the top of his field.

In fact, a vast majority of them don’t.

“There are presumptions out there that once players are in the minors they’ll make it to the majors and to millions, but that isn’t necessarily true,” said Antonia Baum, president of the International Society for Sport Psychiatry.

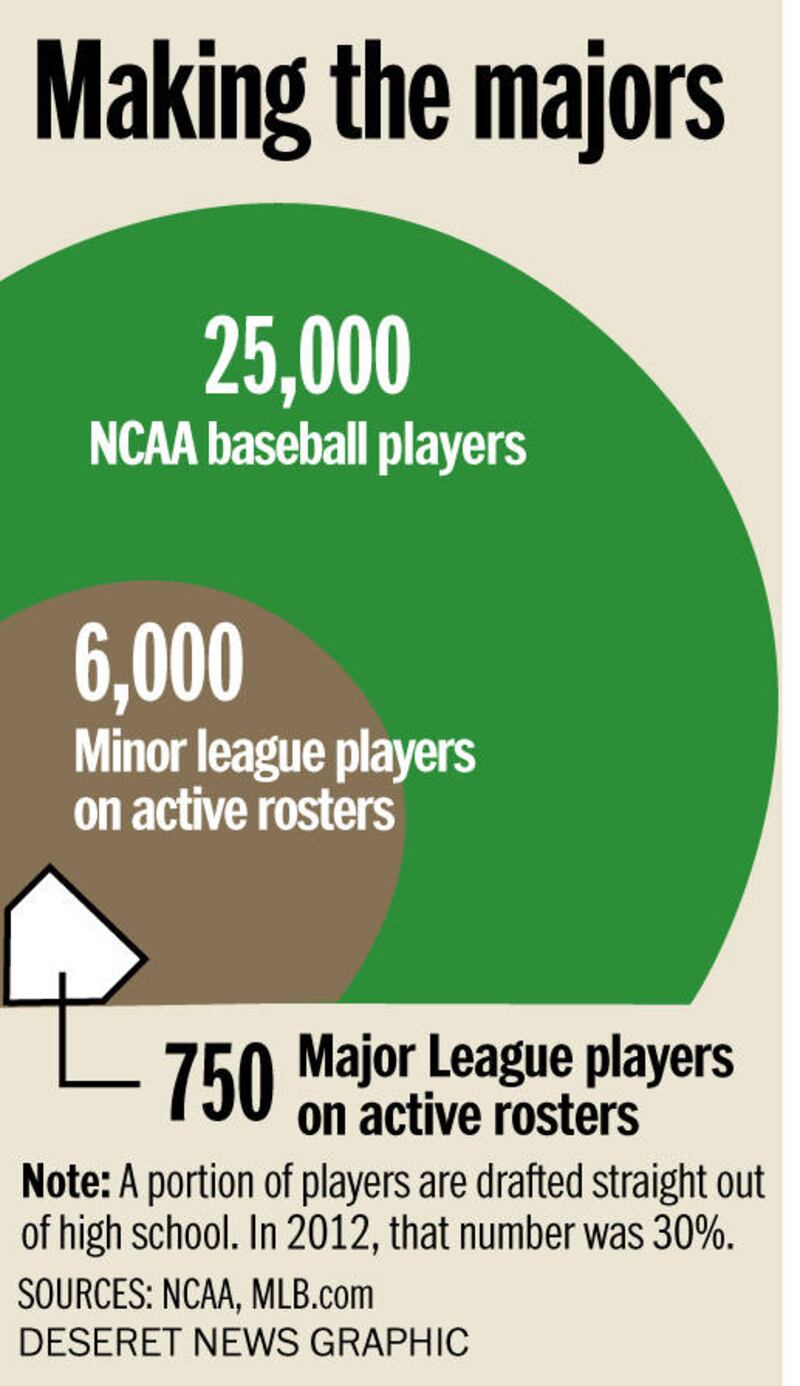

Of the 455,300 high school baseball players in America, less than one percent are drafted into a Major League Baseball club from high school and only 5 percent play on a collegiate team. Of that 5 percent of collegiate baseball players, only 10 percent are drafted to a major league ball club. That’s 600 players drafted out of 130,000 collegiate baseball players, meaning not only being the best player on a team, but the best player in a region. But those 600 players aren’t guaranteed millions of dollars. Many professional baseball players start out as seasonal workers on minor league teams, making around $1,000 a month, with a travel stipends of about $25 per day — less than minimum wage.

In many ways, the public's view of the life of a minor league baseball player has been whittled down to little more than what constitutes a fair wage for minor league baseball players. On one side, fans see the minor league system as a short-term hazing — put in your time, then you'll make the big bucks. Others see it as Major League Baseball clubs bending the rules of the Fair Wage Act, labeling players "seasonal workers," thereby ineligible for minimum-wage rights. The debate has surged beyond just words and speculation and reached litigation levels as two groups of former minor league players have filed suit against MLB, stating that being paid a seasonal wage violates the national minimum wage. The case isn't set to go to trial until 2017.

But for players with families, like Herrmann, playing baseball in the minor leagues is made up of a whole host of decisions, pushing beyond the question, "how much will I make?"

The reliever

The sun hangs just over the top of the stadium seats of Smith’s Ballpark in Salt Lake City. The voices of Katy Perry and grooves of Maroon 5 are punctuated by the crack of wooden bats and thump of cowhide baseballs hitting leather gloves. Herrmann sits in the dugout, just a few hours away from a game attended by around 2,000 fans.

Herrmann doesn't have to be here. With that economics degree from Harvard, he could be making over $100,000 per year working an 8-to-5 job managing financial accounts. But slaving away behind a desk just doesn't compare to the pitching mound.

“All my college roommates, they were making good money banking, and they told me, ‘Trust me, the cubicle will always be there, play as long as you can.’”

And so he’s done that. Hermman is 31 and this is his tenth year playing professional baseball after being drafted by the Cleveland Indians in 2006. He logged three seasons in the major leagues from 2010 to 2012. Today he's playing Triple-A ball for the Salt Lake Bees. And he and Johanna can't believe he's made it to this point.

"We never thought (Frank) would be playing baseball this long," Johanna said. "But when he made it to Triple-A, we realized he had a real chance to make it to the major leagues … since then it's been all about staying there and getting back there, and putting everything else on hold," Johanna said.

In many ways, putting everything else on hold meant living a nomadic lifestyle. They decided that with Herrmann playing baseball, Johanna should also work. She has had jobs in both Atlanta and Southern California, which meant both she and Herrmann have been flying all over the country in order to see each other. When they had their son Franco in 2014, family time often meant Johanna flying red-eye flights with a young baby in order to see Dad pitch a few innings and then a quick hug and kiss before separating again. This arrangement often left Johanna nurturing a baby alone, and Herrmann wishing he could do more.

"I know it's hard for him because he obviously wants to help us and wants to be really hands on, and he definitely is, but at the same time he has to be at the field really early every day (during the season) and he never really knows when he's going to pitch, so it's on me as a wife to make sure he's as ready as he can be each day," Johanna said.

Both Herrmann and Johanna understand that things are tough sometimes living apart. Herrmann knows he has a responsibility to play the best he can, as his family is sacrificing so much for him to play baseball. Johanna understands there's a chance her husband could miss the delivery of their baby girl in July, with a 10-hour drive separating them. She also understands their small family needs to make the most of Frank's league-maximum 72 hours of paternity leave.

"Before having a family it was tough for him, getting to the field at 4:30 a.m. to start working out and (then) playing all day, but I can imagine it's the most difficult time now," she said.

The difficulty for the Herrmanns is that that small window of time also overlaps with spending time together as family. And that makes for myriad tough calls. Just recently, Herrmann got to spend 36 precious hours with his wife and son before having to fly back to Salt Lake for his next game.

"You always dream of professional baseball, but being home after not seeing my son for six or seven weeks — I feel guilty leaving again. It's tough," Herrmann said. "I always want to be really good at everything I do and that includes being a father. And not being there — it's tough to be the father I want to be when I'm not there for weeks at a time."

It's difficult to encompass all the decision-making that goes into Frank and Johanna's lives with regard to their family and Frank's career as a baseball player in one short and sweet explanation. But there's one hour in Frank's day that really encapsulates the constant balance he tries to keep.

"The biggest decision Frank makes on a day-to-day basis is the hour that he could either get to the field early and be one of the first ones there, or stay and have lunch with us," Johanna said. "It's always really hard for him to leave us each day, with a baby and me being pregnant. And when he's at the field, I don't think he ever stops worrying about us," she said.

By now, the Herrmanns have grown accustomed to minor league baseball life. Fourteen-month-old Franco has logged enough hours to have his own frequent flier card. Johanna has learned to feed, clothe, bathe and take care of a baby on her own and still make time to watch nearly all of Frank's games, either in person or on MiLB.com. Frank has worked through rehab for Tommy John's surgery and is working toward a return to the majors. In short, it's difficult for everyone.

“It’s as tough for the kids and wives as it is for the players,” Herrmann said.

The journeyman

Over 2,000 miles away in Florida, Jonathan Weber has a slightly different fatherhood story. Known as a “journeyman,” Weber has played in the minor leagues since 1999. In that time he has won 10 minor league championship rings and an Olympic gold medal; but he hasn’t been called up to play a single game in the major leagues. Weber attributes that to many factors: For example, he always sat backseat to players who had more money invested in them, he never sucked up to managers, and he didn't "know the right people." But one factor Weber sees as a big help in making it to the majors is family.

“The (players) who have good people to back them and a good family and a good supporting cast — that goes so far,” Weber said.

Describing his childhood as “not all peaches and cream,” Weber said had he grown up in a better situation and made better decisions on his way to professional baseball, things might have been better for him.

“People told me to keep grinding — but I had kids and mouths to feed. Once my son was born, (baseball) didn’t come to me as a dream. It was reality. That’s why I’m kicking myself. Had I not partied and drank my way through college, things would be different.”

Today, Weber is divorced, with two kids. He drifts from field to field, season to season, country to country, doing the only thing he knows how. He says a call at 9 o'clock at night may have him on a plane at 6 a.m. the next morning to play ball and is not irregular.

“Is that a good way to live? I wish I still had a wife and kids, but not everyone signs up for the same thing,” Weber said.

The decisions

It's the bottom of the ninth at Smith's Ballpark in Salt Lake City. Herrmann sits in the pitcher's dugout on a hard plastic lawn chair, watching his team play against the Sacramento River Cats. There was a chance he might pitch tonight, but he wasn't needed to close out their one win in four against the River Cats.

Herrmann always focuses on the game at hand, but he also occasionally thinks of his family at home, knowing that his wife is watching his game after putting baby Franco to bed. He wishes they could be here. Or he could be there.

And sometimes, he wishes Franco were just a bit older.

"You never want to fast-forward through anything obviously, but I wish I could have (Franco) around to experience these things that so many young kids want to experience, like being in the clubhouse or on the field during warmups," Herrmann said.

Fatherhood has changed Herrmann's life. He had an idea it would. But he says he never knew how much it would change until it did. The biggest change has come in the form of sleep — or lack thereof, which, Herrmann says, any parent can relate to.

But it's hard to really understand it without living it — even with Facebook.

"On Facebook, people post things about their kids all the time, and you say, 'Geez we get it, he eats cereal, big deal.' But then it's your kid and it's the coolest thing in the world. You feel like a sucker, but you love everything they do," Herrmann said.

"You appreciate little things more, your life completely changes and you gain an appreciation for that kind of stuff."

The game ends, a 9-5 win over Sacramento. Next Herrmann hits the locker room, grabs a bite to eat, changes and showers. He checks the text message from his wife:

"The baby is sleeping. Headed to bed soon. We miss you! Talk to you in the morning."

He texts her back and smiles. The offseason is a long way off, but right at this moment, being with his family 24/7 sounds pretty good.

He leaves his glove and cleats in his locker and heads home to his bare basement apartment, ready for some sleep.

Then he'll do it all again tomorrow.

Email: nsorensen@deseretnews.com

Twitter: sorensenate