Marisol met Pedro in 2009, in the town plaza in her hometown, a small village outside Veracruz, Mexico. She was on her way to study with a friend when Pedro approached her, saying that he was visiting and looking for something fun to do. He was tall, and his hair was gelled into spikes with bleached tips. Marisol didn’t think he was particularly handsome, but he was a salesman in his family’s garment business, and he had his own car.

In a dusty, poverty-stricken village like Marisol’s, 20-year old Pedro was an accomplished young man. He asked for Marisol’s number. She was 16.

Marisol’s mother, like many people from poor towns in Mexico, had gone to the United States five years earlier looking for work. She cleaned houses and sent money home to Marisol’s grandmother, who took care of her. Pedro and Marisol had long talks on the phone when he was back in his hometown of Puebla, or on the road for work. He called her "princess," and took her on dates for ice cream when he visited. After a couple of months, Pedro asked for Marisol’s hand in marriage, and he brought his family to meet Marisol’s grandmother.

But when Pedro took her home to live with his family, they didn’t go to Puebla like he said. They went to 250 miles away to Tenancingo, a town about an hour outside of Mexico City in the Tlaxcala region, that is the sex-trafficking center of the country. Some locals refer to Tenancingo as “Pimp City.”

It’s unclear how many young girls like Marisol are brought to Tenancingo every year, but estimates are in the thousands. Here they will learn that the men who courted them are not fiancés, but pimps, that the mothers are part of the family business and that they have become caught in the brutal machinery of the sex trade.

Tenancingo is a clearing house of sorts, and from there, girls like Marisol will be moved to lucrative urban centers like Mexico City and the U.S., like California, Texas, and New York.

Activists estimate hundreds of thousands of women in Mexico, including young girls, are coerced or forced into sex work, though the secretive nature of the trade makes it impossible to know the exact numbers. The fight against sex trafficking is complicated by cartels that are moving into the business, and gangs like the Zetas, a criminal army formed by defectors from the military, have moved into the lucrative sex-trafficking industry.

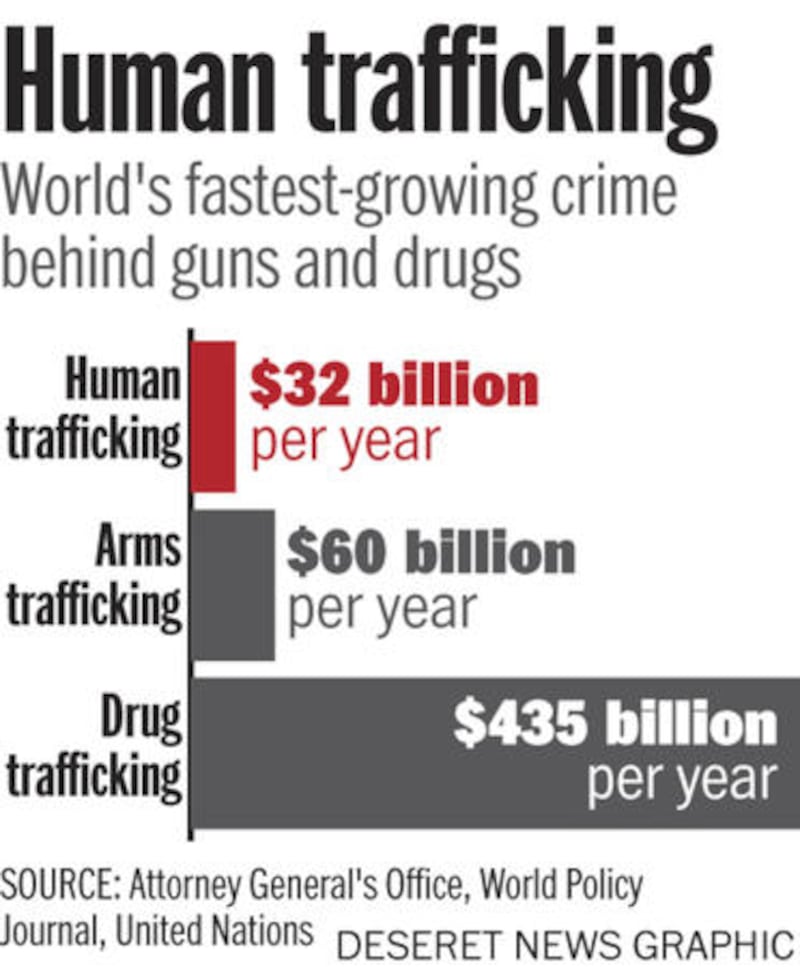

Compared to trafficking drugs, women and girls are relatively easy to procure through feigned relationships and kidnapping, and easy to legally transport. Conditions of poverty and lack of opportunity keep vulnerable girls and young women in constant supply through promises of love or a chance at a better life. The U.N. estimates the global industry for sex trafficking to be $32 billion a year.

“There are parents who are searching and searching for their children and can’t sleep because of this nightmare,” said Rosi Orozco, a former congresswoman who served as a Mexican federal deputy and drafted an anti-trafficking law that passed in 2012.

“If narcotics traffickers are caught, they go to high-security prisons, but with the trafficking of women, they have found absolute impunity," Orozco said.

Marisol, now 22, is in law school. She favors tailored clothes and smart accessories. Today she’s wearing a rose-colored gingham-checked shirt with matching pink gemstone earrings that suggest someone more put together than the average grad student. She has an easy laugh and dimples that play around the corners of her mouth, and a certain cheerful poise that makes her seem older than she is. She’s one of 13 girls and women under the care of Camino a Casa, a rescue home for sex-trafficking victims in Mexico City.

All the girls and women at Camino a Casa were rescued during police raids in Mexico City’s red-light districts, and now they live here, in a securely guarded location, where they get schooling, therapy and new chance at life. The youngest girl here is 11 years old.

The street

On Circunvalación Street, a chain-link fence separates the traffic from the storefronts. Even during daylight hours, you can drive by and see girls lined up against the fence waiting for customers.

This is the notorious La Merced red-light district. Prostitution is legal in Mexico City, and the juxtaposition of sex work and regular commerce seems surreal here, where the storefronts offer cheap luggage, clothes, shoes, candy and on the sidewalks out front, girls are for sale.

In front of a series of popular bike shops, four or five girls in four-inch heels and tight jeans or mini skirts stand languidly outside, talking to each other, waiting. Most look young. It’s difficult to guess whether a given girl is 15 or 18. A waifish girl with dark skin and high cheekbones is approached by a 30-something man in jeans and a messenger bag. They go back and forth in negotiations. A moment later, she walks down a broad alley toward an unmarked hotel with a chipping gray façade, and he follows a few feet behind.

La Merced is where Marisol was taken for her first day of “work.” Pedro took her to a cheap hotel, one of many on the streets and alleyways of La Merced. He said that he had found work for her as an "escort" to "hang out with guys." She was locked in a room with another woman named Jasmin, who asked her if she knew how to use a condom on a man. Marisol was confused — she thought she was working as an escort.

“What do you think we are doing?” Jasmin laughed at Marisol’s naiveté. “You are here to have sex with guys.”

She remembers clearly her first day on the street: “I remember the stands, the food, the smells, the people with bad faces," she said. She felt like throwing up. She had never slept with anyone but Pedro.

Pedro had created a fake ID and birth certificate for her, which he gave to the hotel manager. The papers said she was 18, even though she was 16. No one asked if she was there by her choice.

Jasmin gave her high heels and a short Lycra skirt to borrow, and they lined up at the fence. Marisol was shaking. When the first man approached her, he was about 32, she said, and short. He seemed common to her, not rich. He delivered what she would come to know as the usual introduction: “Hello, How are you? How much?”

Marisol started to cry, so Jasmin came over and scolded her, saying she would scare clients away.

You don’t have to take all your clothes off, Jasmin assured her. “Just take off your skirt and let the man do his business.” The price was 200 pesos for 20 minutes with her — about $16 — and 65 pesos for the hotel.

Marisol, like most girls in La Merced, was expected to have sex about 15 times a day working two six-hour shifts. She was expected to keep a quota, and her pimp collected the money. She would see little of it. Girls who don’t keep up can expect to be intimidated or beaten.

Pedro’s fake romance with Marisol seems like an unlikely, time-consuming ruse. But feigned romance is the most common story among victims here, and it pays off handsomely. A girl like Marisol will bring in over $1,500 US in a single week for a “padrote” — or pimp. A pretty girl can be moved into more expensive markets and to the United States where the figures double.

Other women are kidnapped, tricked with offers of cleaning and cooking jobs, or sold by family members, only to be raped or forced into sex work.

Sex trafficking has boomed in last few decades from places like Mexico, India, Thailand, Russia and the Ukraine, to right here in the U.S. It happens in every country. UNESCO estimates that sex trafficking now generates $32 billion a year. Of that, $15 billion is made in industrialized countries.

Sex trafficking is the fastest-growing criminal activity in the world, behind arms and drugs, according to UNESCO. It’s the largest crime in the world against women and girls, and preys on those who live in poverty and will take desperate risks or scams to get out.

In 2012, Mexico passed an anti-trafficking law, led by Orozco, but convictions are still rare.

“It’s not just about goodies and baddies,” said Ulises Haro, a Mexico City journalist who worked on the 2014 documentary “Pimp City,” following the cycle of drug trafficking through Tenancingo. “It’s the economy that supports the whole town, the whole area. It’s a family business and an economy in a very, very poor place. So it’s hard to crack.”

Orozco said police are part of the solution and part of the problem. Girls tell her stories of police raiding hotels, only to rape girls. For many of the victims, police come in as customers. So women don’t know who to turn to for help.

“The very people who are supposed to be rescuing them are part of the system,” said Orozco.

A safe shelter

Camino a Casa is, appropriately, housed inside a former drug cartel home seized by the government. It’s circled by high concrete walls and the entrance is manned by a full-time security guard. Inside, the yard is lined with mango and magnolia trees, and the spacious rooms of the home are filled with light.

What was once the cartel family’s expansive glass dining room table is now surrounded by girls, chatting, drinking coffee, and eating rice and beans for lunch. Upstairs, they bunk together in bedrooms painted bubble-gum pink. The girls have decorated the walls with handwritten posters with messages like “Dios no olvida sus promesas,” God doesn’t forget his promises, that are covered with frog stickers and daisies colored in orange marker. On first glance, it could be an ordinary dorm at a sleep-away camp.

Christina, 17, has lived here for two years since her rescue. She studies online learning modules to catch up in school. One of the challenges of getting victims back on their feet is that they have missed crucial years of their education.

The grueling life of sex trafficking robs girls and women of their education, and of their self-esteem, said Fernanda Paredes, the outreach advisor at Camino a Casa. “They are told that they aren’t good enough to do anything but sex work, and after a while, they believe it,” said Paredes.

Every girl who arrives here has an STD, said Paredes, and mental health issues. Some have to be sent to detox for drugs, which have been forced on them for coercion or that girls use to self-medicate as a coping mechanism.

But pimps in Mexico have hit on a much more effective coercion tactic than drug addiction. Within the first year, pimps try to make sure that a victim is impregnated. When she gives birth, he takes the child away and his family will raise the child, allowing the victim to visit a couple of times a month. This form of emotional bondage is extremely effective.

“Most women will die in a brothel before they will abandon their child,” said Paredes.

This happened to Karla, who was a troubled 12-year-old when she was seduced by a man 10 years her senior in a fashion similar to Marisol’s. She had her first baby when she was 15, and eventually had two children with her pimp.

“I had a baby girl, and after one month, he took her away,” said Karla. “After that, instead of threatening my family, he threatened me with my daughter.”

Camino a Casa is outfitted with a new swing set in the yard where on a warm day this spring one former victim is playing with her two children, ages 3 and 4. She lives with them here now, but many women are not so lucky. Being rescued can mean being separated from a child — sometimes for months or maybe for years.

On the other side of town, Benny Yu runs Well of Life, a smaller, humbler shelter wedged between a bakery and an apartment building in a residential neighborhood. The courtyard, where girls listen to music and color pictures of Disney characters, is covered by a tarp. Nine girls live here, ages 9 to 17.

When I walk in with Benny, two small girls, who are no taller than my shoulder, come running to greet us at the door. They led us to a kitchen that smells of butter and vanilla where the girls were making tiny thumbprint cookies topped with candies and rainbow sprinkles.

Ariana and Elisa, who met us at the door and pressed warm cookies into our hands, are only 11 and 13. They were brought into the city and sold into sex trafficking by an uncle.

Despite the sad history here, Yu's place is cozy and buzzes with girlish energy. At a table nearby, girls scribble busily into coloring books. Down the hallway, another cooking project — caramel apples — is in progress. It’s three in the afternoon, and studies are done for the day.

“We try to keep them busy,” said Yu. “Idle time leads to trouble.”

He is referring to the little spats that can break out between young girls living in close quarters. Emotions can be close to the surface. Sixteen-year-old Jessica is helping a younger girl fill in a Precious Moments coloring book drawing of an angel surrounded by clouds. When I ask her if she likes it here, her face clouds over instantly.

“They are very nice to me here,” she said as her voice catches. “But I want to go home to my family. I haven’t seen them for a long time.”

Later Yu will tell me Jessica was sold by a family member and authorities have to determine if it’s safe for her to return.

“There’s also the issue of shame,” said Yu. “Sometimes their families don’t want them back after they have been 'prostitutes,' or girls can’t bring themselves to go home.”

Anti-trafficking has picked up in Mexico City, where last year there were 86 raids on hotels and massage parlors, rescuing 118 women. Over 60 traffickers were arrested. But this is still a drop in the bucket, said Orozco: “We know there are possibly hundreds of thousands of women trafficked in Mexico, and thousands of pimps," she said.

Camino a Casa and Well of Life comprise two of the three victim shelters in Mexico City. Paredes said none of the women from her shelter have gone back to the streets, though it is a common problem. Without a shelter, therapy and education, it can be almost inevitable, she said.

“These girls are trafficked as children, and with no education, and no family, prostitution is the only way they know how to survive unless given alternatives," she said.

Taking back the night

Women who are trafficked in Mexico City are often trafficked to the United States — especially New York and New Jersey. In a 2008 Homeland Security Investigation bust in New York City, authorities arrested 13 sex traffickers with connections to Tenancingo.

California, Texas and the New York area are all sex-trafficking hubs in the U.S. with ties to Mexico. The inequality between the borders creates a situation that is “ripe” for sex trafficking, said Blanche Cooke, a former federal prosecutor and professor at Wayne State University's Law School.

“It’s like a gold mine for sex traffickers,” she said

The real problem, said Cooke, is that we live in a world that for centuries has seen women and girls as property, and sex trafficking is an extension of that.

As a scholar and activist, her work, she said is to “stop problematizing women,” in other words, stop prosecuting the victims, and go after the suppliers and the sex buyers who are creating demand.

Until 2013, the FBI didn’t track human trafficking data as part of its uniform crime report, so there hasn’t been reliable data to understand and prosecute it. There are additional barriers in the ways sex-trafficking victims are defined. Bridgette Car, director of the Human Trafficking Clinic at the University of Michigan said trafficking victims are treated as victims within the federal criminal justice system but as prostitutes in local jurisdictions.

Cooke said the female body is more sexualized and objectified than ever, and, therefore, female bodies are associated with products, with something that can be consumed.

“We protect property under our laws better than we protect the bodies of women,” she said. “We assume that a stranger has no right to be in your house if you get burgled, but if you’re over 18, under the law, you have to prove force or coercion for a sex-trafficking charge.

“It’s terribly interesting because the presumption is that a victim is consenting unless the government can prove otherwise. That doesn’t exist for any other kind of crime.”

It’s part of a prevailing male fantasy permeating our culture, said Cooke, that is perpetuated in popular culture and pornography, and also manifests in rape culture.

“The fantasy is that women want to be prostitutes, that it’s a legitimate job or them,” she said. The answer, she said, is to provide more and better opportunities for women, so they are not in desperate situations requiring them to take risks.

Marisol, who was trafficked at 16 in La Merced, puts it another way: “No girl wants to grow up to be a prostitute,” she said.