On Aug. 20, 1940, communist leader and Russian exile Leon Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico City. Trotsky had long been an opponent of Soviet leader Josef Stalin and the evolution of communism in the USSR under his direction.

Around the turn of the 20th century, two factions emerged within the fledgling Russian Social Democratic Party. The majority of the Russian socialists believed in a strict reading of Karl Marx. This meant that the most industrialized nations on Earth at the time — Britain, Germany, the United States — would have communist revolutions first, while Russia, largely agrarian, would have its revolution only after it fully industrialized.

The industrial proletariat, the workers, must be educated in Marxist theory before a revolution could be successful. This was the philosophy adopted by Trotsky.

The second, smaller faction, championed by Vladimir Lenin, argued that a professional revolutionary cadre could lead the people in a revolution, and then, after the revolution had been achieved, it could educate the people in Marxism.

This ideological division deepened during the second party congress in 1903. Because Czar Nicholas II's secret police had been successful in cracking down on the illegal party, representatives met in London. On virtually all of the major issues, Lenin's faction was in the minority. When a vote on a minor matter concerning the party's newspaper Iskra (Spark) was taken, however, Lenin had the votes he needed to get his way. He seized on the results of this one anomalous election and branded his faction the Bolsheviks (majority), while the other faction, the actual majority, was branded the Mensheviks (minority).

The division between these two factions remained deep, and each considered the other heretical. Prior to the 1917 revolution in Russia, Trotsky had already made his name as a figure in the international communist movement and was arguably more well known outside of Russia than Vladimir Lenin. When the Russian Revolution broke out in February 1917, Trotsky was in New York City, but he quickly made his way back to Russia. At this time Trotsky changed his views and became a Bolshevik. The time had come for a true communist state to emerge in Russia, regardless of Marx's view on historical development.

After the Bolshevik Revolution against the provisional government occurred in October, Trotsky became the commissar for foreign affairs and the creator of the Red Army. He negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany, which essentially handed the other nation massive amounts of land, resources and population that had belonged to the Russian empire. Trotsky and Lenin, who led the country until his death in 1924, believed it was a delaying tactic. Germany would soon have its own communist revolution and what was signed away would be given back by German communists.

As the “dictatorship of the proletariat” struggled to introduce pure communism to Russia, while fighting a civil war against anti-communist Russians, Trotsky often butted heads with Lenin and his attack dog, Stalin. Stalin proved not nearly as intellectually brilliant or personally dynamic as Trotsky, but he did have a quality in abundance that Trotsky lacked to the same degree: ruthlessness.

After Lenin's premature death from a stroke in January 1924, Trotsky found himself with little support in the Soviet leadership, including Stalin. Other leaders viewed him as a johnny-come-lately to the Bolshevik fold, and still others were offended by his apparent contempt for the emerging Soviet bureaucracy. (Indeed, Trotsky was known to read French novels while his colleagues debated Marxist theory.)

Still others viewed Trotsky as dangerous. The lessons of the French Revolution were not lost on the Bolsheviks, and Soviet leaders were on the lookout for a Napoleonlike figure who would seize power for himself. Since Trotsky had created the Red Army, many feared he would use it as a tool to launch a coup.

Fear of Trotsky drove many Soviet leaders into a political alliance with Stalin, whom many believed to be gruff but ultimately controllable. Lenin himself had warned against Stalin having too much power in his final testament, stating that his attack dog was “too rude” to lead.

Ironically, it was Stalin who turned out to be the Napoleon figure of the Russian Revolution, using not the military, but the Soviet bureaucracy, as his power base. Eventually anyone who wanted to get anything done had to go through Stalin, and, in turn, each of his political "allies" was marginalized or arrested. Because of Trotsky's standing, he was Stalin's first target. Sentenced to internal exile in 1927, the next year Trotsky was forced to leave the USSR.

(Trotsky's standing as an international figure, and Stalin's belief that Trotsky still had many followers within the Soviet Union, ensured that he didn't get a bullet in the back of the head, the common form of Bolshevik execution.)

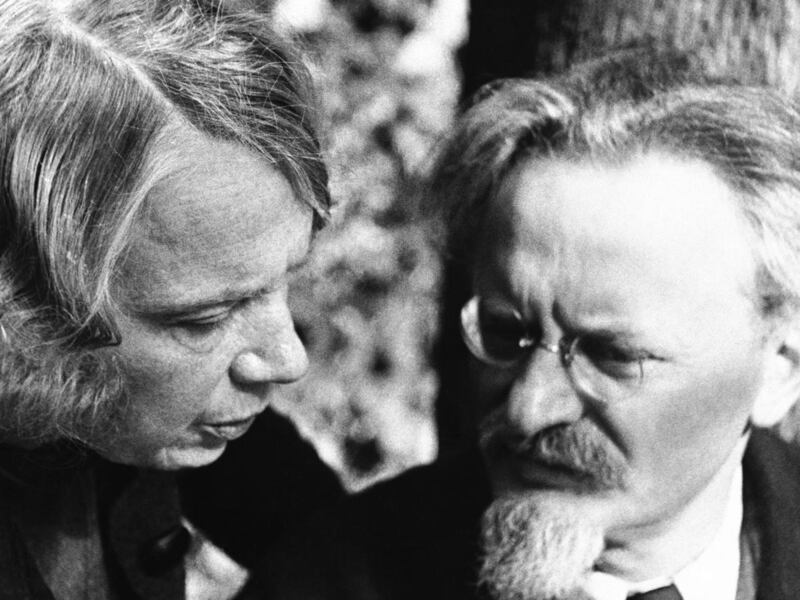

Trotsky and his wife lived in France and Norway before settling in Mexico. For a time, they lived with artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in the Coyoacán district of Mexico City. In 1939, they bought a house in the same district. Throughout all of his exile, Trotsky remained a critic of Stalin and the state of communism in the Soviet Union. He wrote political discourses attacking the regime in Moscow with biting words like “the Revolution Betrayed” and “the Stalin school of falsification.”

Trotsky also organized the Fourth International, communists from around the world who agreed with Trotsky's interpretations of Marx and Lenin and who detested Stalin's supposed perversion of communism in Russia.

By 1940, Stalin believed it was time to end Trotsky's attacks. World War II was raging in Europe, and though the Soviet Union was as yet a neutral power, Russia could easily be drawn into the conflict. It was no time for potentially dangerous dissenters to make trouble. In the book “Stalin: A Biography,” historian Robert Service wrote:

“The hunting down of Stalin's mortal enemy had involved a large diversion of resources from other tasks of espionage. Nevertheless, the Soviet spy network was not ineffective in the 1930s. Communism was seen by many European anti-fascists as the sole bulwark against (Adolf) Hitler and (Benito) Mussolini. A small but significant number of them volunteered their services to the USSR.”

In May 1940, a pro-Stalinst group led by the Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros attempted to murder Trotsky. Disguised in police and army uniforms, the gang rushed the guards in front of Trotsky's home, set up machine guns and began firing into the villa. Trotsky and his family were unhurt, and the would-be assassins fled.

Undeterred, Stalin ordered another attempt. The Spanish communist Ramón Mercader began dating Trotsky's secretary and visited the villa many times. A trusted friend and apparent follower of Trotsky's politics, Mercader appeared at the villa on Aug. 20 and asked Trotsky to read a political paper he was working on. Within his long raincoat, however, Mercader hid a pickaxe, a tool he had used many times while mountain climbing.

In the book “The Great Terror: A Reassessment,” historian Robert Conquest wrote: “Trotsky had two revolvers on his desk, and the switch to an alarm system within reach. But as soon as he started to read Mercader's article, the assassin took out his ice axe and struck him a 'tremendous blow' on the head.”

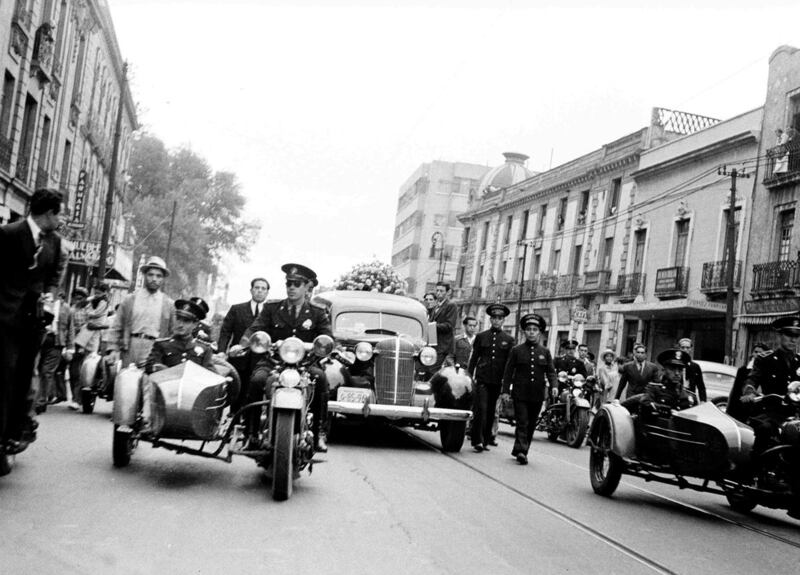

Contrary to Mercader's intention, Trotsky did not die. Rather, the assassin later stated, he let out “a cry, prolonged and agonized, half-scream, half-sob.” Trotsky's security guards, hearing the howl, rushed into the room and quickly grabbed Mercader. Trotsky was taken to the hospital, where he underwent an operation, but the trauma and blood loss proved too much for the revolutionary. He died the next day at the age of 60.

In Moscow, Stalin celebrated and awarded Mercader's mother a medal, and not long after Mercader's release from prison in 1960 he was awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. As Conquest noted, Trotsky himself had made an odd prediction concerning his old rival Stalin that eventually came true. He wrote in 1936:

“He seeks to strike, not at the ideas of his opponent, but at his skull.”

Cody K. Carlson holds a master's in history from the University of Utah and teaches at Salt Lake Community College. An avid player of board games, he blogs at thediscriminatinggamer.com. Email: ckcarlson76@gmail.com