On Facebook earlier this month, members of the Indian Hills Elementary School PTO learned that two children at the school in Riverside, California, were being tested for Hansen's disease.

One parent posted, "Oh my gosh, did you look up what that is???"

The parent, Jana Eberle, was shocked to learn that the innocuous-sounding Hansen’s disease is leprosy, the dreaded malady of biblical times. In Jesus' time and before, people with leprosy were driven from their homes and forced to wear bells around their necks to warn others of their approach. The 13th chapter of Leviticus spells out rituals surrounding leprosy and instructs anyone who has it to wear torn clothes and call out "Unclean!"

Today, however, leprosy has a new name, and for all practical purposes, can be considered a different disease, given the vastly improved outlook for anyone who contracts it.

Leprosy is curable and difficult to transmit. You're more likely to catch it from an armadillo than a classmate or co-worker. It's believed that 95 percent of people have natural immunity. Yet the disease can still evoke horror, as administrators of the California school found out.

While they were waiting to learn whether two students suspected to have Hansen's disease actually had it, some parents sent their children to school wearing surgical masks; others kept them home in the days after the announcement.

Officials announced Sept. 22 that one of the children tested positive, but assured the community that there is no risk to other students.

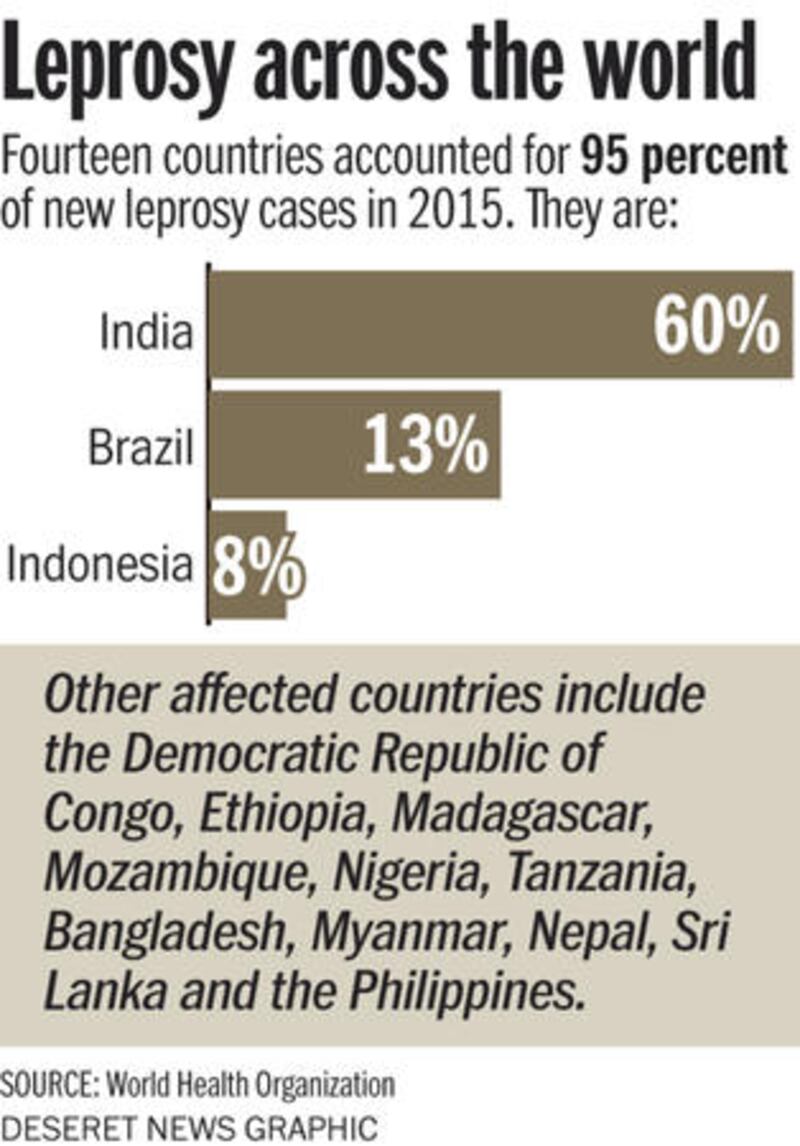

Leprosy remains a problem in some countries — most notably in India and Brazil — and there are still about 200 cases that emerge each year in the U.S. But if you don't have a pet armadillo or travel extensively, your risk of getting leprosy is microscopic.

"It's just not that communicable. Most people are immune, and the germ is fragile. The impression most people (of the disease) is just wrong, and their fear is irrational," said Dr. David Scollard, the recently retired director of the National Hansen's Disease Program, which coordinates care for patients within the U.S.

The stigma associated with Hansen's disease, however, has been difficult to erase, partly because of its biblical heritage; partly because just a half-century ago, people diagnosed with the condition were essentially imprisoned.

A home with no hope

In Bergen, Norway, there is a museum devoted to leprosy; it's where Dr. Gerhard Armauer Hansen discovered the bacterium that causes the disease (Mycobacterium leprae) in 1873.

There's also a leprosy museum in the U.S., in Carville, Louisiana, where leprosy patients were involuntarily confined for more than a century.

"If you were diagnosed, you were sent there," said Elizabeth Schexnyder, curator of the National Hansen's Disease Programs Museum.

Originally called "The Louisiana Leper Home," it was at first run by four Catholic nuns. Their numbers had swelled to 116 by the time the facility was turned over to the federal government in 1921. It eventually had more than 100 buildings on nearly 400 acres. Until successful treatments were developed, beginning in the 1940s and eventually leading to a total cure in the 1980s, it was a prison for the sick.

"Of all the records we had, no one ever left the Louisiana Leper Home. There was little or no hope of being released. Some people ran away and came back of their own free will; others were brought back by the sheriff," Schexnyder said.

When it was discovered that some treatments for tuberculosis also helped those with leprosy, patients were allowed to leave for two months every year. Later, an effective combination of therapies still used today allowed the national "leprosarium" to be closed.

Today, the Louisiana National Guard occupies the site, save for the 6,000-square-foot building that was once the staff dining hall and is now the museum. The property also is the burial site for more than 1,000 Americans who had leprosy, including one former patient who died just last year.

'A disease of poverty'

Leprosy, however, isn't fatal. People can die of complications from it, but not from leprosy itself, which is why people have historically feared the disease. "It could cripple and disable but not kill," Scollard said. The bacteria move slowly, which is why it can take years for symptoms to develop. It prefers cooler temperatures, which is why it prefers the surface of human skin (and the footpads of armadillos).

Untreated, its effects are visually horrific. The infection destroys nerves, leading to ulcers, sores and eventually the loss of sensation in extremities. Body tissue dies and becomes deformed, giving way to the signature clawed hands and feet of leprosy, and many untreated patients will become blind.

Bill Simmons, president of American Leprosy Missions, based in Greenville, South Carolina, said while Hansen's disease is rare in the U.S., it clusters in a handful of nations, with 65 to 70 percent of cases in six countries. There is no vaccine, although there is a clinical trial under way in India and another about to begin in the U.S.

Founded in 1906, American Leprosy Missions has a staff of about 30: half in South Carolina, and the rest around the world. Its work includes helping governments set up education and treatment programs, as well as providing education about Hansen's disease; it recently developed a textbook for clinicians.

"Our mission hasn't changed, but where and how we go about it certainly has," Simmons said, noting that leprosy is largely a "disease of poverty."

While Simmons, like others who work with leprosy in the U.S., was aware of the scare in California's Riverside County — and wonders how news of yet unconfirmed infections was made public — he said it's highly unlikely that any children could contract Hansen's disease from a classmate, even before the school was disinfected.

"There is no recorded incidence of secondary transmission of leprosy in the U.S. in recent history," he said. Most people who present with the disease here are immigrants who contracted it years ago while living in a country with more cases, or people who have come in contact with armadillos.

The hard-shelled creatures, which live in Southern states, seem to have a genetic propensity for the disease and can carry the bacterium on their feet. American armadillos probably caught it from a human host centuries ago, Scollard said. Not all armadillos are infected, however.

And unlike mosquitoes, which transmit Zika and other diseases, "at least armadillos can't fly," Simmons said.

And as horrific as leprosy has been throughout thousands of years, Americans have no reason to fear it, he said. Depending on the degree of exposures, leprosy can be cured by taking two or three drugs for one or two years.

"There's very little chance that I would ever contract it, but if I did, I would just take antibiotics and go about my day," Simmons said.

EMAIL: Jgraham@deseretnews.com

TWITTER: @grahamtoday