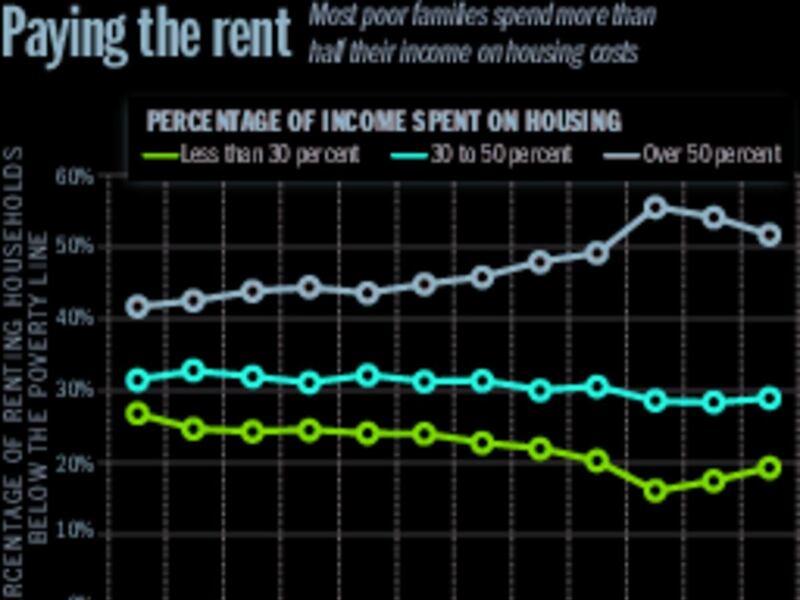

Renters in the U.S. are paying an increasing share of their incomes for housing, according to the American Housing Survey. As of 2013, most poor renting families spent more than half their income on housing costs, and nearly a fourth spent 70 percent or more — well above the recommended 30 percent most Americans spend.

Low-income renters are hardest hit: if a family's monthly income is $850 and rent is $600, it's nearly impossible to make ends meet.

As rents have skyrocketed, so have evictions. One in eight poor renting families couldn’t pay all their rent in 2013, and a similar number worried they would be evicted soon, according to the AHS.

Sociologist Matthew Desmond wanted to understand the phenomenon of eviction, so he got as close to the problem as he could. In 2008, Desmond, now a Harvard University professor, moved into a trailer park and then a rooming house in inner-city Milwaukee. He met families facing eviction and spent his days sitting with them through eviction court proceedings as well as church services, births, funerals and everyday life events in their homes, slowly earning their friendship and trust.

Desmond’s new book “Evicted” traces the lives of eight of those families, including two single moms, a double amputee father, a couple expecting a child and a young woman fresh out of foster care. He also follows two landlords making tough calls that will have lasting effects on these families’ lives.

Desmond describes his experience as heartbreaking and depressing, but said he also learned about hope and humor in the face of tragedy and hopes his work will inform needed reforms.

Desmond talked with the Deseret News about his experience in Milwaukee and potential solutions to the U.S. affordable housing crisis that balance the interests of tenants and landlords.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Deseret News: What happens when someone is evicted?

Matthew Desmond: Eviction causes loss. You lose not only your home but often your possessions, which are either put on the sidewalk or taken to a mover's storage facilities. Many tenants can't make payments, and when they don't, their stuff just gets hauled to the dump.

You lose your neighborhood and your community. Your children often lose their school, and we have good evidence that workers lose their jobs.

Eviction also comes with a record. If you're registered through the court, that not only prevents you from accessing decent housing in good neighborhoods because many landlords refuse to take you. Public housing authorities also turn you away when you apply for public housing. That means we're denying that aid to the people who need it most.

Then there’s the toll eviction takes on your spirit. We have evidence that moms who are evicted report higher rates of depressive symptoms two years later. So you add all that up, take a step back and look at all those consequences, and you have to conclude eviction is a cause, not just a condition, of poverty. It's making things worse.

DN: You talk in “Evicted” about the concept of “home” and why it’s important to individuals, neigborhoods and countries.

MD: Home is the center of life. It's the wellspring of personhood. It's where we say we're ourselves. Everywhere else we are someone else, but at home we remove our masks. Home is where children find safety and security, where we find our identities, where citizenship starts. It usually starts with believing you're part of a community, and that is essential to having a stable home.

This is why without stable shelter, everything else falls apart.

DN: What are some particularly poignant stories from your experience in Milwaukee that have stuck with you?

MD: I think you remember the hard ones. I remember Arleen and her children getting evicted on a day that was one of the coldest days in Milwaukee history — it was 40 degrees below with the wind chill. I remember being on evictions and seeing these people's faces, just being overcome with the fact that their home was no longer their home.

But I also remember a lot of generosity, a lot of humor and a lot of spunk and courage in the face of adversity. There's a scene in the book that always moves me. It's of these two women, Vanetta and Crystal, in a McDonald's. They were homeless and they were eating lunch, and they saw a boy walk in. He didn't go to order — he went around looking for scraps at the table. He was hungry. These two women — who were homeless — pooled their money, bought him lunch, gave him a hug and sent him on his way.

Those moments showed me just how clearly people refuse to be reduced to their hardships. I would call it having heart.

DN: In your experience following two landlords closely as you wrote this book, what would you say about the common caricature some people paint of “slumlords?”

MD: I never use the word slumlord in the book. You'll never see me writing it other than when people say it and it's in quotes. I think we let ourselves off the hook a bit if we say, “Oh, these tenants are just irresponsible,” or “These landlords, they're just greedy.” It's way more complicated than that.

My job was to really understand landlords by getting as close to them as I could — to understand why they evicted you but not me, to understand why they bought property in the inner city. The book does not shy away from things landlords do to increase their profit margins. That means disinvesting from housing, that means evicting tenants that have called a government inspector on them.

The book addresses all those points, but it also addresses times when landlords let tenants slide, when they buy them food, when they let tenants who have really hard records into the properties. That the whole picture is something we have to really look at.

DN: Walk us through a brief history of low-income and government housing in the U.S. How did we get to where we are now?

MD: Just a few generations ago, we had slums that were ravaging our cities. Kids were dying of tuberculosis; there were outhouses in the middle of Philadelphia; poor people were living without heat and running water. We took that on as a problem and we won.

I'm not naive that we still face housing problems in poor communities — the trailer I lived in most of the time didn't have hot water. I get it. But there's no arguing that we've made huge leaps forward in terms of housing quality, and we did that by building public housing and eradicating or replacing the slums. But then we defunded public housing and we allowed those giant towers to turn into slums themselves.

We’ve now replaced generally public housing with new initiatives based on housing vouchers, where we give a voucher to a tenant and allow them to move into the private rental market at a subsidized rate.

But most low-income families don't get anything. Only one in four people who qualify for any kind of government aid for housing get it. It's not because people are being turned away. It’s literally because the waiting lists are years and years and years long. In Boston and D.C., the waiting list for public housing is counted in decades. We have not as a nation invested to a degree that comes close to meeting the need.

DN: You mention two solutions: legal representation and expanding the housing voucher program. Say a little about each of those.

MD: Low-income tenants do not have any right to counsel in civil courts, unlike in criminal courts. So in many housing courts, potentially 90 percent of tenants are unrepresented while landlords by and large have attorneys.

If we invested in a public legal service for indigent tenants in housing court facing the rich, that would curb frivolous evictions, make sure that we stopped illegal evictions and allow a tenant's case to be made — unlike in the majority of cases today.

Seventy percent of tenants summoned to eviction court in Milwaukee don't show up. I bet you and I wouldn't show either if we knew we'd have to face off against a landlord. This is a way we can invest in costs upstream to stem the cost downstream that we all incur because of eviction's fallout.

But that's not going to address the underlying huge problem, which is the lack of affordable housing in our cities.

My proposal is the universal voucher program. We take this program that's already working fairly well and we expand it to all families below a certain income level. It would be a massive intervention into poverty in America. It would make evictions rare again. It would stabilize families and communities, and it would allow children to reach their full potential.

Email: apond@deseretnews.com

Twitter: @allisonpond