On March 19, 1945, Adolf Hitler issued his infamous “Nero Decree,” which called for the systematic destruction of Germany. The order was largely thwarted by Hitler's armaments minister, Albert Speer, and highlighted Hitler's waning authority as the Third Reich collapsed.

At the height of World War II, Hitler's empire stretched from the Pyrenees Mountains of southern France in the west to the gates of Moscow in the east; from the deserts of North Africa in the south to the Arctic Circle in the north. Virtually all of Europe had fallen to or been allied with Nazi Germany, and the totalitarian state seemed unstoppable.

Historians have offered many “turning points” in the war, which ultimately led to Hitler's defeat, but one fact is undeniable: By invading the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, Hitler overreached. The Wehrmacht's first major blow came in December of that year when it was stopped before the Soviet capital. Until that point, Hitler's army had conquered every continental foe it had come across. Only Britain, safe behind its navy and the English Channel, had remained outside of Hitler's sphere.

The invasion of Russia signaled four years of the hardest, most brutal fighting the world had ever seen — before or since. The Soviets learned their lessons from history, emulating their ancestors who had resisted Napoleon 130 years earlier. One of Russia's greatest strengths was its immense territory, which always allowed room to retreat and regroup — but just as critically, it forced the invader to keep extending supply lines, which grew more tenuous with every mile advanced.

Because lines of supply were so extended, the German High Command ordered the Wehrmacht to live off the land, stealing food and necessities from the Russian people wherever they could. With Hitler as with Napoleon, Russian peasants began burning villages and crops, denying the invaders sustenance and shelter, and forcing them to rely more and more on the vulnerable jugular of their supply lines. Hitler appreciated the Russian scorched earth policy even as his armies suffered its effects.

By 1945, Hitler's empire had shrunk considerably. Allied forces had landed in Normandy, France, in June 1944, and had quickly liberated the country and turned their armies eastward. At roughly the same time, the Soviets had launched Operation Bagration, a massive offensive that expelled the Wehrmacht from Russia and saw the Red Army advance to the gates of Warsaw. By March 1945, the Third Reich consisted of Germany proper, a few territories in central Europe, northern Italy, Denmark, Norway and some of Holland.

The proverbial writing on the wall was that the Allies would soon win the war — Germany was just not powerful enough to stop them. Yet Hitler persisted in his belief that the war could still be won. He frequently noted the differences between the capitalist West and communist Soviet Union, and stated his conviction that the unnatural alliance between the Allies would break apart once they both made it to Germany. Then, Hitler imagined with twisted logic, the Western Allies would ask for his help to destroy the Soviets. What Hitler failed to realize was that he was the fundamental cog keeping the Allies together. Their mutual hatred of him far outweighed their misgivings about each other.

Filled with this self-delusion, and growing increasingly desperate as the Allied armies began to probe into Germany proper, Hitler decided he would emulate the defense his armies had encountered in Russia: The German people would destroy everything that could be of possible use to the Allies as they advanced.

Hitler had retreated underground to a fortified bunker in the Reich Chancellery gardens in January 1945 to seek refuge from the Allied bombing. His meetings in these last few months were humid, claustrophobic affairs in which dozens of military officers, civilian officials, staff and courtiers were present. One frequent visitor to the bunker was Albert Speer, Hitler's minister of armaments.

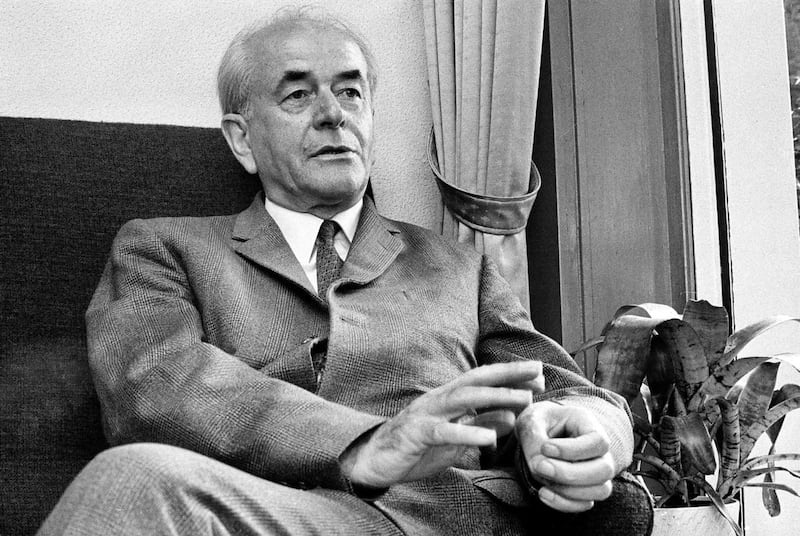

Young, good-looking and brilliant, Speer had been a member of Hitler's inner circle for years. Originally an architect, Speer had dazzled Hitler with his grand designs based on Hitler's own crude drawings, and the Führer saw in the other man a kindred artistic spirit. As the war progressed, Hitler bestowed upon Speer more and more authority, and after the death of armaments minister Fritz Todt, Hitler gave him that portfolio as well.

With the Third Reich crumbling down around them, Speer knew Hitler's mind and issued a memorandum stating his objections to the destruction that the Führer was considering. Hitler, however, was of one mind. On March 19, 1945 — coincidentally, Speer's 40th birthday — Hitler issued his decree: “Our nation's struggle for existence forces us to utilize all means, even within Reich territory, to weaken the power of our enemy and prevent further advances. …”

The order empowered local Gauleiters (district Nazi Party leaders) and Reich defense commissioners with carrying out the order. Factories, farms, power plants, railroad lines, bridges, military and supply installations, dams, and more were all to be blown up or otherwise permanently disabled. If followed to the letter, the order would have seen Germany reduced to a pre-industrial economy and standard of living after the war. Officially, the order was called “Destructive Measures on Reich Territory,” but it was nicknamed the “Nero Decree,” after the emperor who presided over Rome during the great fire of A.D. 64.

After the meeting in which Hitler informed his generals and courtiers of the order, Speer met privately with the Führer, who offered the younger man birthday wishes. The two had been at odds before, and their relationship had grown considerably cooler over the last year and a half. Still, as Speer later noted, if Hitler had been capable of true friendship, he would have been his best friend.

Hitler offered him a signed photograph and apologized that the inscription was barely legible because of the shaking in his hands. Speer presented his master with a new memorandum, reiterating his objections to the call for destruction. Hitler took it and promised he would offer a written response. By the end of the interview, the warmth that Hitler had greeted him with was completely gone.

According to Speer's memoirs, “Inside the Third Reich,” Hitler then told him: “If the war is lost, the people will be lost also. It is not necessary to worry about what the German people will need for elemental survival. On the contrary, it is best for us to destroy even these things. For the nation has proved to be the weaker, and the future belongs solely to the stronger eastern nations. In any case, only those who are inferior will remain after this struggle, for the good have already been killed.”

A few days later, Hitler replied to Speer's memorandum, stating that the armaments minister was wrong in his assessments, and reiterating his earlier position on the need for destruction. Some of the Gauleiters sought to follow their orders, such as Dusseldorf's Friedrich Karl Florian. Most, however, saw the futility of even trying to implement the order. With explosives and military hardware already in short supply, what there was was needed at the front. Military commanders too, such as Field Marshal Walter Model, saw the order as counterproductive to military aims since Hitler had promised that lands taken by the enemy would soon be retaken by German forces — though not even the field marshal really believed that.

When Speer met with Hitler again toward the end of the month, he persuaded the Führer to give him authority over the destruction project. Hitler, by now perhaps aware that his plans would not and, indeed, in most cases could not be carried out, agreed. This was, therefore, most likely a face-saving act for Hitler, who did not want to publicly roll back the order but knew its implementation was hopeless. Speer himself, of course, would theoretically follow the order, though the substance of the decree would get bogged down in the bureaucracy and red tape of the Nazi system.

In the book “Hitler, 1936-1945: Nemesis,” biographer Ian Kershaw wrote: “The non-implementation of the 'scorched earth' order was the first obvious sign that Hitler's authority was beginning to wane, his writ ceasing to run. 'We're giving out orders in Berlin that in practice no longer arrive lower down, let alone can be implemented,' remarked (Propaganda Minister Joseph) Goebbels at the end of March. 'I see in that the danger of an extraordinary dwindling of authority.’”

The order was never fully implemented, and Hitler committed suicide at the end of April. Speer was later arrested by the Allies and placed on trial at Nuremberg, where his resistance to the Nero Decree bought him some goodwill among the judges. Where most of the 21 men on trial were hanged, Speer was one of the few who got off with a jail sentence. He spent 20 years in Spandau Prison in Berlin before being released in 1966. He died in 1981.

Cody K. Carlson holds a master's in history from the University of Utah and has taught at SLCC. He is currently a salesman at Doug Smith Subaru in American Fork. Email: ckcarlson76@gmail.com