He always made you feel safe with him. We (the siblings) all love him. He made us all feel special. He makes sure everyone is included and welcomed and loved. He was a sibling, but he was like a parent to us. – Kalani Sitake's sister Pamrose

PROVO — Kalani Fifita Sitake, BYU’s new football coach, doesn’t think this story should be about him. He believes it should be about the people who helped get him this far, to the corner office of his alma mater’s football complex.

“I didn’t get here by accident,” he says, “but because of a lot of people. That’s what this should be about.”

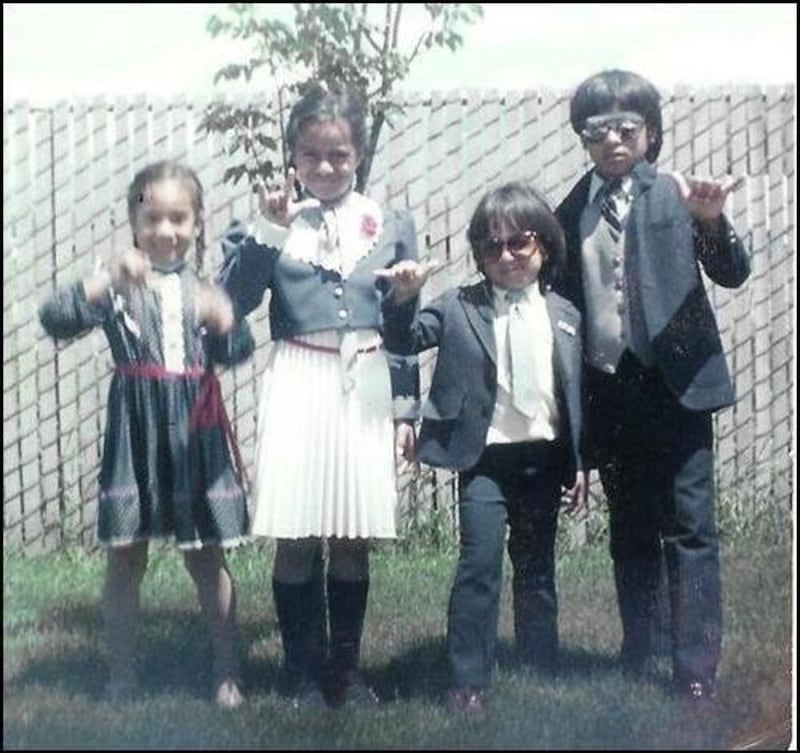

Sitake’s story could begin with his paternal grandfather, Nafe, who left Tonga in the 1960s for San Francisco and then in the years that followed when his 14 children left the islands as circumstances allowed, landing in Australia, New Zealand and the U.S. One of those children was Tom, who sacrificed his own dreams of an education so that his children — Kalani, Toakase (“Toa”), Pamrose and T.J. — could have more opportunities, just as thousands of his countrymen had done for decades. Tom was so serious about education that during the summer he required daily book reports from his kids, due at the end of the day. They would all earn college degrees.

“The dream of my father worked out,” says Tom. “He made sacrifices. I made sacrifices. We have hope for our grandkids. Some of them need to be reminded of the sacrifices others have made.”

Kalani, the oldest of the four children, was two weeks old when the family left the islands. Forty years later, he has risen to the top of his profession, on the shoulders of his grandfather and father. “I am a result of a lot of people caring, and hard work,” he says.

When Tom and his wife and new baby left Tonga, they moved to Laie, Hawaii, and had three more children in four years. Tom enrolled in a master’s program at BYU-Hawaii, but the plan became complicated. Tom and Eseta divorced. She moved to Australia to be near family, and he remained with the children. Tom sent his children to live with relatives in San Francisco so he could finish school, but the kids missed their father, so he moved to San Francisco to be with them and gave up his hopes for advanced education. Six months later they moved to Provo, where other extended family lived.

Tom worked as a security guard, usually graveyard shifts and swing shifts, so he could see more of his kids. Says Tom, “When we got here we talked as a family — We are here now. There will be happy days and sad days. But as family we need to be safe and love one another.”

That message seemed to resonate with the eldest child. No one sums up Kalani Sitake better than his younger brother T.J.: “Kalani was always older than his age, looking back.”

Kalani filled in as a second father for his siblings. He woke them in the morning and sent them to bed at night. He walked them to the elementary school and then sprinted several blocks to the middle school. This led to a big collection of tardy notices, so Pamrose was moved to an afternoon class schedule. Kalani would skip his lunch and run home to walk her to school and then raced back to his own school. At the end of the school day he escorted his siblings home. Sometimes between classes he would dash to the elementary school simply to check on them.

“He was the last to eat and the first to get up,” says Pamrose. “He was the one organizing everything and making sure everyone was OK. He didn’t care if he had the ugliest clothes; he just wanted everyone to be happy.”

At the end of the elementary school year there was a dance festival, and T.J. polished up a routine for the occasion by practicing at home. On the same day, Kalani planned to take a field trip to Lagoon with his middle school class. As T.J. tells it, “He ran the three blocks to watch me do my dance routine. He risked missing the bus — he almost missed it. That meant a lot to me. But that was his mindset: He was always thinking of us.”

It usually fell to Kalani to cook the meals for the family (he was especially good with chicken and rice). “He never complained about it,” says Pamrose. “I’m sure he knew this was unusual. I didn’t realize this was extraordinary until I was in high school. I thought everybody’s brother did that.”

Even after Kalani left home and was enrolled at BYU, he continued to watch over his family. He used part of the stipend from his football scholarship to pay part of the family’s utility bills. When one of his sibilings wanted to play a sport and needed money for equipment or a participation fee, Kalani paid with his scholarship money.

“He’s always been a good big brother,” says T.J.

The Sitakis lived in a two-bedroom, one-bath apartment in which Tom slept in the living room. The family car was old and quirky. For one thing, the heat wouldn’t shut off, so in the middle of July the inside of the car was a kiln. The family didn’t have a washer or dryer; the kids took their dirty clothes to a laundromat. The younger kids tended the washer while Kalani carried loads of laundry back and forth to the house.

“I love and adore Kalani so much,” says Pamrose. In her cell phone, Kalani’s number is listed under the name “Protector.” “He always made you feel safe with him. We (the siblings) all love him. He made us all feel special. He makes sure everyone is included and welcomed and loved. He was a sibling, but he was like a parent to us.”

T.J. and Pamrose named children after Kalani — which means “Gift of Heaven” — and Toa asked Kalani to name one of her children, a great honor in the Tongan culture.

There is one story that sounds like it’s straight from an after-school TV special: One day when Kalani was walking his siblings home from school, they saw several bullies harassing a poorly dressed, heavy-set kid. Kalani, a skinny 13-year-old, approached the bullies — who were bigger and outnumbered him — and told them to leave the kid alone. The bullies turned on him, but Kalani stood his ground and ordered them to leave the kid alone or else. After the bullies walked away, Kalani told the kid to meet them at the same spot every day and he would walk home with him and his siblings.

“And that’s what happened,” says Pamrose. “From then on, he walked home with us.”

Tom talks in equally glowing terms of his oldest child. “I’m not surprised at all what Kalani is doing at this time with his life,” he says, and then he goes silent, trying to control his emotions. After apologizing, he continues, but stops and starts again as he cries quietly. “He’s a kid who never complained — never.”

Tom believed fervently in the power of education, industriousness, his Mormon faith and the discipline of sports. In the summer, he dropped the kids off at the library daily and told them to have a one-page book report completed at the end of the day. He bought old encyclopedias at the thrift store and assigned book reports on certain subjects from the books. “I hated it so bad,” says Pamrose. When school was in session, Tom monitored their studies. Even when his children were in college, he would call their professors to check up on them.

“Education is the only way to survive,” he says.

Kalani earned a degree in English, Pamrose in nursing, Toa in social work and T.J. in sociology. Toa and T.J. are nearing completion of master’s degrees.

“My parents left the islands for education,” says T.J. “It has been central to our family. Part of the reason I’m in a master’s program is to follow through on what my dad taught us — and it’s what I believe, too.”

Tom didn’t permit the waste of time. He wanted his kids to be busy with church and school activities, studies and sports. He placed strict limits on TV and video games. When he came home one day and found them parked in front of a video game, he yanked it out of the machine and threw it in the garbage. “Enough,” he said. “Go outside and play.”

When Kalani was in junior high, his father stopped the car one day and asked him to get out and check the tire pressure, and then he drove off and left him, forcing Kalani to walk and run several miles to their home. This became a routine over the years. “After that first time, anytime his dad would tell him to get out of the car he knew he was running,” says Timberly, the coach’s wife of 14 years.

Tom took his sons to BYU and required them to run the long flight of stairs from the lower campus to the upper campus, or he sent them up and down the stadium stairs. He required a regimen of pushups and situps, and he urged them to play pickup games outside (money being tight, the boys once used an old steel-toed boot as a football, wrapping the laces tightly around it to give it the right shape). All four children played at least two sports in high school.

Following Kalani’s sophomore year at Timpview High, the family moved again. Tom had met and married a woman in Provo and a couple of years later they moved to St. Louis to be near her family. The marriage, which produced two children, crumbled soon after their arrival, but Tom decided to let Kalani, a rising football star who was being recruited by Division I schools, finish high school there.

“I remember coaches from Iowa and Notre Dame coming to our little apartment in the ghetto,” says Pamrose. “It was a pretty rough neighborhood.”

When Kalani moved back to Provo to attend BYU, the family went with him.

They all live in Utah, near their father. Tom is director of vocational rehab at the Utah State Hospital and still hopes to complete his master’s degree. His family has achieved the immigrant’s dream of education and employment.

“I’ve had to lean heavily on people to get this far,” Kalani says as he sits in his office. “My family especially. That’s the story. I’d be fine with no one talking about me. I’m not accustomed to being in the spotlight.”

Sadie, Timberly, KK, Kalani and Skye Sitake at home in Provo on Friday, March 11, 2016.

Sitake, a powerfully built man of 40 who has not completely overcome his childhood shyness, has been thrust into the spotlight anyway. The irony is that football once afforded him a measure of the anonymity that his shyness craved. He could hide under a helmet and pads, and a football field provided a buffer between him and the crowd. “You’re safe,” he says. It was only when he began serving an LDS Church mission in Oakland that he was forced out of that comfort zone, out of his shyness.

“It’s uncomfortable; you get rejected and you’re on your own and living on a tight budget,” he says. “So you’re struggling and at the same time you’re preaching something that has so much value. That helped me more as a coach than anything else.”

And now football has pushed him out of anonymity. He has been an increasingly visible figure the last few years, first as defensive coordinator at Utah and then at Oregon State. Along the way he turned down several offers to be an assistant in the National Football League and a defensive coordinator at several other Division I programs.

“My wife and I didn’t feel like it was the right thing to do,” he says.

Job offers came his way, especially when he was an assistant at Utah, and this surprised him because he didn’t seek such opportunities. He was a hot commodity for many reasons: His rapport with players and people in general; his ability to express himself well; his intelligence; his reputation as an outstanding recruiter, and, yes, his race, which opened a pipeline for Polynesians, a people culturally and physically suited for the game. He gained a reputation for recruiting Polynesians.

“I’m kind of offended when they say I’m a Polynesian recruiter,” he says mildly. “Some players happen to be Polynesian, some African-American, some white. I value all of them. I’m just a coach who happens to be Polynesian.”

He is only the third Polynesian to hold an FBS head coaching job — after Norm Chow (fired by Hawaii a few months ago) and Ken Niumatalolo at Navy) — and they all share at least one other trait: They are all Mormons.

“Kalani’s appointment was monumental to all Polynesians,” says Vai Sikahema, the former BYU star. “Our Polynesian community has a vested interest in Kalani's success because his success is our success.”

Almost the first thing Sitake did after winning the BYU job was to call coaches and former BYU players seeking their advice and support. One of those calls was to LaVell Edwards, the legendary BYU coach who retired in 2000, the same year Sitake, his starting fullback, graduated. In a lengthy conversation, he sought Edwards’ opinions about constructing a team and a staff and the other challenges of the job.

“It was a great conversation,” says Sitake. “I took notes. He talked a lot about what I would go through and the things he experienced here. I just listened and wrote down as much as I could. It was an honor.”

Sitake also called, among many others, Kyle Whittingham, his mentor and boss at Utah, Gary Andersen, who hired Sitake as an assistant at two different schools, and Sikahema, who has known the Sitake family since before Kalani’s birth.

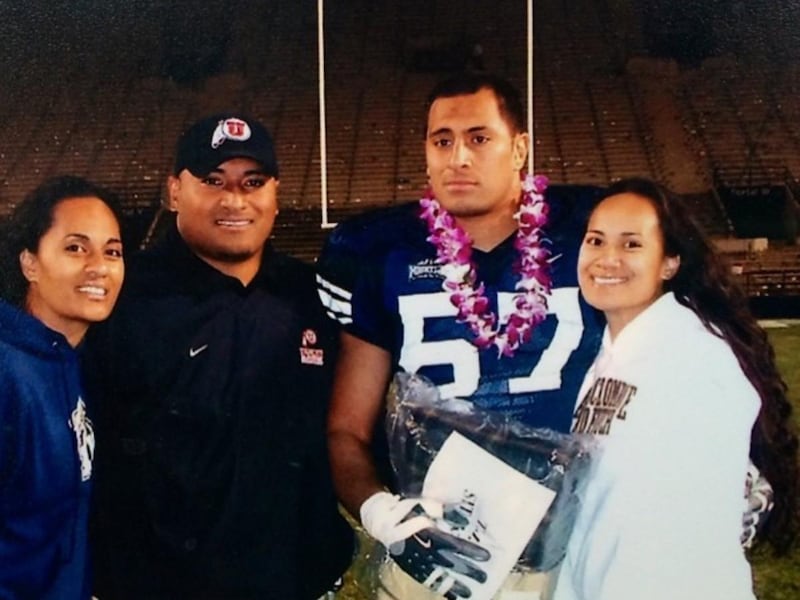

Toa, Kalani, and Pamrose pose with TJ on his senior day before his final home game at BYU. Kalani was a coach at Utah at the time.

“Kalani reached out to me with these wonderfully written text messages,” says Sikahema. “In one of them he wrote, ‘I can’t do this job alone. This job is bigger than me ... This place, this program, this school changed all our lives in significant ways. I need your support.’ It was very heartfelt and inspiring.”

Sitake was going to be a math major, but he settled on English — and ultimately football. An English degree seems an odd choice for a coach, although there are others who have done the same, most notably NFL coach/BYU alum Andy Reid. An English major seems an even stranger choice for a Tongan who spoke pidgin English throughout most of his youth. In high school, a teacher told him he would never speak the language well, which provoked his competitive instincts. He earned an A in the class and perfected his pronunciation, which undoubtedly helped pave the way for his current job.

“I enjoyed literature and writing,” he says, explaining his English major.

When the Sitakes moved to Provo a few months ago, books — about 50 boxes of them — took up most of the moving van. “Our poor movers,” says Timberly. “They were saying, 'Have you guys ever heard of Kindle?’ We have some hardcore readers in our family.”

Sitake is one of them. “There’s just something about the feel of a book,” he says.

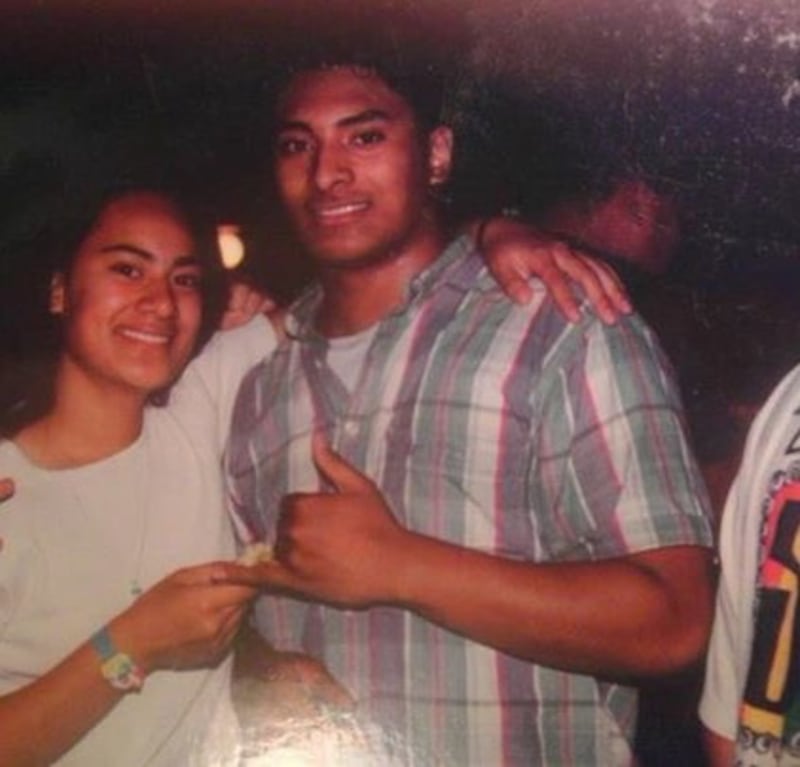

Sitake aspired to teach high school English and coach prep football. The pull of the latter would overwhelm the former. For Sitake, football was joyful and carefree, especially when life away from the field was more complicated. As he puts it, “Football was the best part of my day. I loved it.” Ultimately, he became a coach because he couldn’t resist the game and because his body betrayed him.

As a fullback at BYU, he delighted in blocking, going out of his way to deliver big hits, but it took its toll. At 6 feet, 245 pounds, he appeared indestructible, but he was rarely completely healthy. He sustained a back injury. He had bursitis in his knee. He dislocated an ankle and broke a leg on the same play. He tore a pectoral muscle. Even to this day he can partially dislocate both shoulders at will — subluxation is the medical term. “There isn’t a day that I don’t feel pain,” he says.

Used primarily as a lead blocker and receiver, he had only 86 rushing attempts and 373 yards while playing from 1994-2000, but he caught 62 passes for 536 yards and two touchdowns. He was healthy enough to stay in the lineup as a senior, but he was still nursing injuries. “I was just trying to survive,” he says. He was offered a free-agent tryout with the Cincinnati Bengals and reinjured his back. “So that was that,” he says.

All these years later it still bothers him. “Everything has been better than what I hoped for in my life,” he says. “My playing career was the most disappointing thing I’ve done.” This is not a complaint; if that is his biggest disappointment, he considers himself blessed.

”Football ends for everybody,” he continues. “I just wish I could’ve been healthy. I loved it so much and I still wanted to play, but my body wouldn’t allow it. I thought there’s got to be something else.”

He planned to seek a master’s degree in English, but couldn’t shake the football habit. He was coaching at a BYU football camp when one of the other coaches told him about a coaching position at Eastern Arizona. “I thought, OK, here I go,” he says. He coached there for a year and “loved every second of it.”

He was all-in after that. He coached five different positions at three schools — BYU, where he worked on a master’s degree as a graduate assistant coach, and Southern Utah and Utah. After a decade with the Utes, he was lured to Oregon State as a defensive coordinator in 2015 and then BYU called.

Once he began coaching, he immersed himself in it, as he tends to do with everything he undertakes. Perhaps he explained his drive recently when he said, apropos of nothing, “Whatever you’re doing, you aspire to be great — in football, as a student, whatever. I’ve always aspired for great things.”

In his spare time he talked to coaches around the country trying to pick up tips, always taking notes, as is his habit.

Even as a player at BYU, he was unusually interested in the intricacies of football. During an injury-forced redshirt season, rather than stand around shooting the breeze with teammates, Sitake studied film for hours “trying to learn as much as I can.”

Says Edwards, “When he was a player for us I remember thinking he could be a good coach, whether it was because of the notes he took or the questions he asked. He was always prepared.”

While coaching at Utah, Sitake sat down with Whittingham and former NFL coaches Dennis Erickson and John Pease, among many others, to pick their brains. When Whittingham became a head coach, Sitake says, “I watched him carefully to see how he would interact with and manage the staff. I took notes on a lot of things.”

Sitake wasn’t too proud to adopt ideas anywhere he found them. On one occasion a little league coach told him about a practice drill. Sitake took notes and created a drill that is very similar to what the coach described.

“I’m kind of a nerd that way,” Sitake says.

While coaching at Utah he discovered a library of videotape that had belonged to the late Fred Whittingham, Kyle’s father and a former NFL coach and player who had been a defensive coordinator at Utah and BYU. Some of it was archived Utah and BYU film and some of it was old NFL film that consisted mostly of practices and drills. It was tedious stuff for most, but Sitake was a kid in a candy store; he made notes about drills and techniques and schemes.

“It was the teaching I was intrigued with — seeing how they teach,” he says.

Sitake is almost always this focused. He is a serious, intense, quietly driven man who suffers from insomnia and likes to stay up late simply to think. Early in their marriage, Timberly would find scrap pieces of paper around the house on which were scribbled notes her husband had dashed off. There was no order to them and they covered a wide variety of subjects.

“Kalani was just jotting things down on anything he could find and I would find these papers everywhere,” she says.

She began buying him notebooks — “so I would know what I couldn’t throw away” — and now he carries them everywhere. He has a vast collection of notebooks and he fills them with thoughts about family, faith, football and his musings for the day. It’s partly a journal and partly his continuing education. He took four pages of notes while listening to a recent athletic-department discussion about strengthening relationships. He filled several more pages during a staff meeting.

“He reads his notes later,” says Timberly. “I think note taking is very reflective for him.”

His intensity notwithstanding, Sitake prides himself on this: “When I come home my kids can’t tell if I won or lost.”

“Not at all,” confirms Timberly. “Even the kids would have no idea if he won or lost. He is very steady.”

“When I was a child, I cared so much about those games,” Sitake says. “I still care, but I care about my family more. It’s a game, and it’s important and I’ll give it everything I’ve got, but when I’m with my kids that’s my game there … We don’t have a lot of time and we’ve got to make it count. I’m getting nervous that they’re getting older.”

Sitake, in the midst of his first spring camp, has done his homework and prepared for this job, as much as that is possible. “It’s a big leap, no matter how ready you think you are,” says Whittingham. “Until you experience it, you can’t appreciate it. But Kalani is a quick study and a smart guy.”

“This is a dream job for him,” says Timberly. “Whatever comes along with that, he has been in heaven. He’s exhausted but happy.”

Doug Robinson's columns run on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. Email: drob@deseretnews.com