The influence of the Bible on world history cannot be exaggerated. Its greatest significance was obviously religious, but it has also influenced all aspects of Middle Eastern and European society. One could argue that the most significant cultural passage in the Bible is Exodus 20:4-5: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them.”

In the most straightforward reading, these verses forbid the creation of representational art in any form. Paradoxically, however, a few chapters later, the Lord commands the Israelites to make images of cherubim to decorate the tabernacle (see Exodus 25:18-20, 26:1).

These verses thus created a conundrum for subsequent Jewish, Christian and Muslim artists. Should art be completely forbidden under any circumstances? Can one create geometrical, non-representational religious art as long as it does not represent divine things? Are we allowed to make images of the human life of Jesus, as long as we don’t represent him in his divine form? Are images of God or angels permissible as long as you don’t “bow down” or “serve” them? And is there a distinction between “venerating” a religious image (showing respect and honor), and “worshipping” an image?

Greek Orthodox theologians made an important distinction between “graven images,” as carved three-dimensional statues (forbidden), and two-dimensional paintings or mosaics (permitted); Catholics eventually permitted both.

The significance of these theological questions was not merely for arcane debates by obscure medieval theologians. Many of these questions had tremendous impact on the course of cultural history.

Eastern Christians suffered over a century of political revolutions and civil wars over the question of state sponsorship of religious images (A.D. 726-842). The Protestant Reformation included a strong element of iconoclasm, when accumulated centuries of religious art were systematically destroyed because they violated the second commandment.

Whatever the relative theological merits of these centuries-old debates, Western art would have been greatly impoverished if the more “liberal” interpretations on religious art had not been adopted throughout most of Christendom.

The earliest surviving Christian art dates from the late third century, and it tends to depict biblical stories, including scenes from the life of Jesus. It included both paintings and sculpture, stylistically following Roman pagan models.

Only in the early fourth century, when Constantine inaugurated a massive church building and decoration program throughout the Roman empire, do we find a fully developed Christian art. The nature of the relationship between Father and Son was the most vexing theological question in the history of Christianity, and these issues are often reflected in early Christian art.

Depiction of the divine Jesus in human form was universally accepted because of the incarnation. But what of the Father? Is he anthropomorphic? Should he be depicted in art? And if so, how?

Although Christ was widely represented in early Christian art as both human teacher and resurrected God, God the Father first appeared only as a human hand reaching through the veil of the heavens to teach or bless, such as in the apse mosaic in San Clemente in Rome.

The most prominent artistic depiction of Jesus became the risen Christ enthroned in heaven after the resurrection (Christ Pantocrator, “ruler of all”), which appeared in the domes or apses of most Greek Orthodox and Catholic churches throughout most of the Middle Ages, such as in the 12th-century painting "Christ Pantocrator" in the Cefalu Cathedral in Sicily.

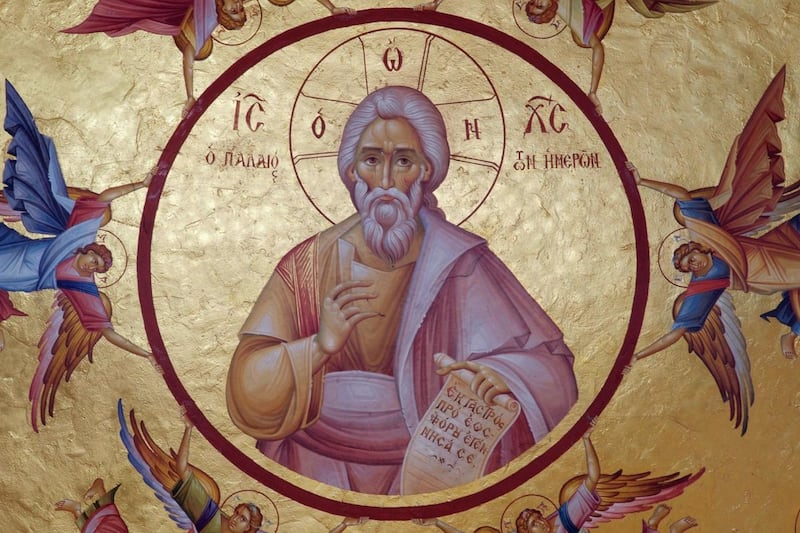

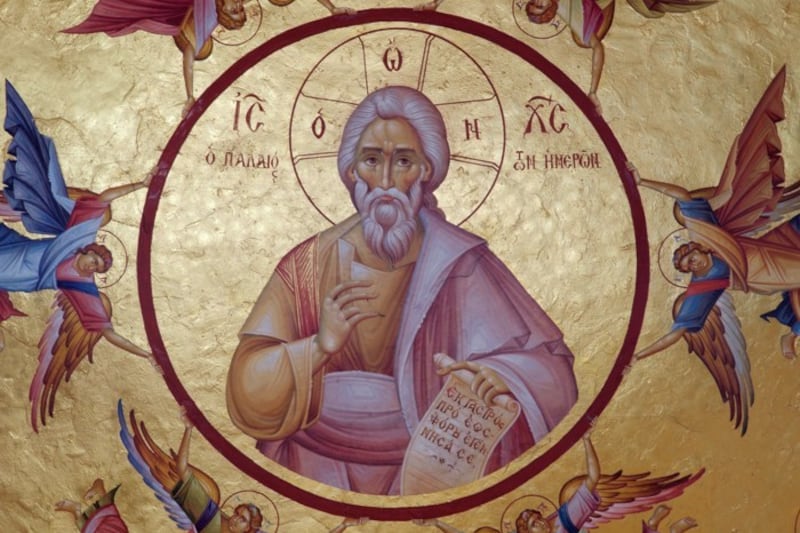

In such examples, Jesus is a man in his 30s, with long brown hair and beard. But sometimes he is depicted as the “ancient of days,” an old man with long white hair and beard, such as in "Ancient of Days" in the Capernaum Greek Orthodox Church, Israel .

In general, however, it is the Father who appears as an old man. These theological ambiguities of the relationship between Father and Son are often reflected by similar ambiguities in Christian art. Photo three is clearly the Son, since it is marked with the Greek Christian abbreviation “IC XC” for “Iesous Christos” (Jesus Christ).

By contrast, in the 19th-century painting in the dome of the St. George Monastery in Israel, the old man is clearly the Father because in Greek theology, the Holy Spirit — in the form of a dove — proceeds from the Father only, and not the Son.

In the long run, it became standard Christian iconography for the Father to be represented in anthropomorphic form as an old man, often side by side with the younger Son, with the non-incarnate Holy Spirit as a dove, such as in the "Trinty," an El Greco painting in the Prado Museum in Madrid. .

Daniel Peterson founded BYU's Middle Eastern Texts Initiative, chairs The Interpreter Foundation and blogs on Patheos. William Hamblin is the author of several books on premodern history. They speak only for themselves.