Garrett Rush-Miller was 5 years old when doctors gave him a 50 percent chance of surviving to see his 10th birthday.

That was in June 2000, when he was diagnosed with a brain tumor that, once removed, left him blind, mute and paralyzed. He survived the surgery to remove the tumor, but his father, Eric Miller, said after the surgery, his once-outgoing son became reserved and introverted.

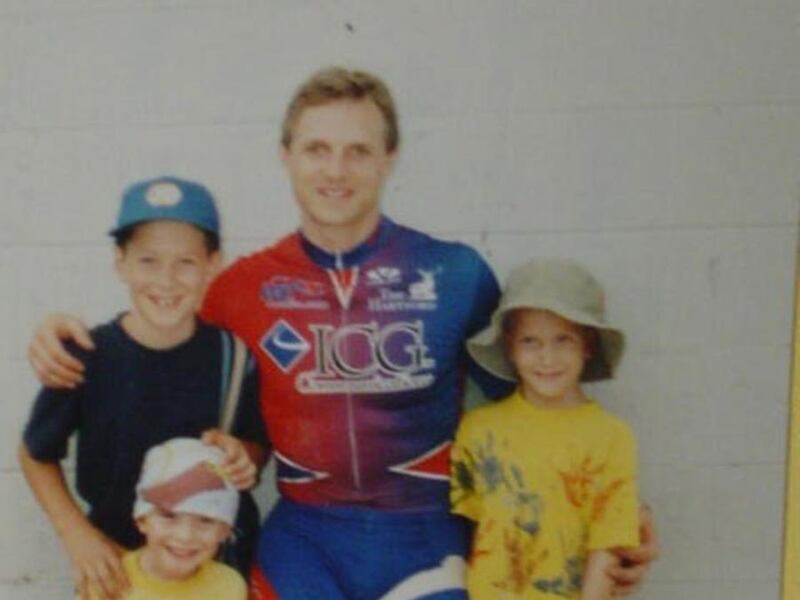

After two years of relearning how to walk and talk, Rush-Miller was still visually impaired and hesitant to play with his friends outside. To inspire his son, Miller took him to see Paralympian Matt King — who is also blind — compete in a tandem bicycle race in late August 2000.

Rush-Miller had never seen a tandem bike before, and as he ran his hand across King's bicycle, something happened; Miller remembers it as if a "switch went on" behind his son’s eyes.

"It was like having my son back," he said. "He couldn’t quite understand how the cyclist would be able to balance and use a cane — he thought you would sit on the front of a bike and use a cane versus the one blind person sitting on the back."

Miller, a flight nurse in the Wyoming Air National Guard, and his ex-wife, Nancy Rush-Miller, decided to get a tandem bike for their son shortly thereafter, which Miller said transformed his son into the "star of the neighborhood" again.

At that point, Miller realized he wanted to offer families with similar circumstances the opportunity to give their children tandem bikes. By February 2001, the Rush-Miller Foundation was operational.

Miller now works out of Pueblo, Colorado, with bike manufacturers DHS and Cannondale as well as local bike shops around the country, providing other blind children with their own tandem bicycles. He's provided bicycles for children in 43 states and eight countries since 2001. His latest project includes donating two tandem bikes to every school for the blind in the United States. He's already donated two to 24 schools over the past 15 years and plans to continue until every U.S. school for the blind has two bikes.

"We don’t have any paid employees; this is our labor of love to the world," he said. "Our money comes in and goes right back out. While we’re small, I think we definitely make a big impact."

Miller said there are no paid, full-time staff in the organization; his team is composed of five close friends who have full-time jobs but chip in to help when they can.

He doesn't get to see many of the youths he donates to because flights are too expensive for his nonprofit's annual budget of anywhere between $4,000 and $16,000, but he loves hearing from them after they get a chance to ride their bikes for the first time.

"For kids (who are blind) who have never been into bikes before, it’s like this massive thrill," Miller said. "The bike then becomes this conduit to accomplishing other things in your life. If you didn’t think you could ride a bike and then you’re riding a bike, what else could you do that you didn’t think you could do?"

For some of those young people, that bike provoked a total lifestyle change.

One of them, Matt Simpson, will travel to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in September to compete in the 2016 Paralympic Games as a member of the U.S. men’s goalball team.

Goalball is a fast-paced sport that was created to help rehabilitate blind veterans. All players wear blackout goggles to ensure equality as they try to throw balls that have bells inside them into the opposite team's goals.

It also happens to be Garrett Rush-Miller’s favorite sport.

Simpson said receiving the tandem bicycle was one of the defining moments of his athletic career. He was 15 and had never been on a bike before. He quickly took to the sport and immediately began to compete in races and triathlons with his best friend.

"For me it was a path, a stop along the way, but also kind of a springboard into the rest of my athletic endeavors and making the Paralympic team," Simpson said. "Getting the tandem bike and having those experiences of racing against my peers … It taught me to train hard and find that dedication."

He said receiving the bike helped him not just in athletics but in his life.

"Cycling wasn’t something I would ever do, just because my vision wasn’t good," Simpson said. "So many people with visual impairments are confined to the space around them and can’t get out there and experience the world because they’re afraid to take that risk. Having that bike was really a good way to get me out into the world."

Children at the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind in Orem, Utah, had a similar experience after the foundation gave the school two tandem bikes. Many of the youths there who have visual impairments got to experience riding for the first time because of the gift, school communications director Kim Pierce said.

"We’ve had comments about how they didn’t understand the speed, or that some kids didn’t even understand what the wind felt like to go through your hair," Pierce said. "You take that for granted."

She described riding the bikes as "one of their favorite activities."

"The entire time they’re riding they're grinning," Pierce said. "It has been a blast to watch the kids ride around. I wish it was warm all year-round so the kids could ride around — it’s just so cute."

Miller plans to keep the foundation running for the foreseeable future and is focused on completing his school project. He doesn't plan on expanding the size of the operations, saying he enjoys that it has stayed "very simple" throughout the years.

There's only one thing Miller asks in return, he said: that those who receive a bike help raise funds for another family’s bike.

Even after donating at least “a couple hundred” bicycles to families and schools for the blind since 2001, Miller remains humble.

"We’re not curing cancer," Miller said. "We’re just taking kids and putting their butts on a bike."

Email: sweber@deseretnews.com; Twitter: @sarapweber