I feel very fortunate to be here. In one sense, you want to smell the roses and enjoy it, but I’ve got to get focused on day-to-day improvement. – Troy Taylor

SALT LAKE CITY — It was less than a year ago that Troy Taylor was sitting in a small office at Folsom (California) High School coaching the Bulldogs football team, and here he is now, moving into his new digs inside the University of Utah’s $30 million football facility and taking over the offense for a top-25/Pac-12 football program.

That’s a big leap. Then again, maybe this is the introduction of the game’s next big offensive guru. About 10 days after the Utes hired Taylor as their new offensive coordinator, he was offered a three-year contract by “a big-name university.”

“I’m not the only one intrigued (with Taylor),” says Utah head coach Kyle Whittingham. “I had to fight to keep him.”

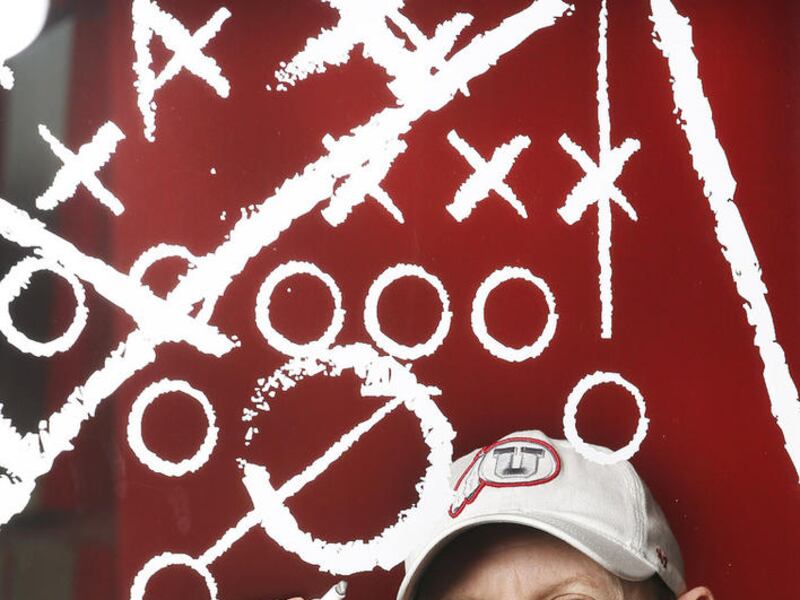

Everyone who spends time with Taylor tends to come away dazzled by his football acuity, passion and success. The new guy is a football junkie, even by football coaching standards. He’s a mad-scientist type who doodles plays on yellow legal pads so much that he goes through two or three pads a week. Twenty minutes after meeting a reporter for the first time he is slashing at a dry erase board with a black marker to show receiver routes and progressions and defensive reactions. At one point, he demonstrates with an imaginary football, eyes scanning downfield, feet set in the wider stance he likes quarterbacks to use.

“I’m consumed with it,” he says. “I’m captivated. That’s who I am.”

This is his second attempt at college coaching. He abandoned the college game in 2000 believing it simply required too much time, and he coached California high school teams for 15 years. After building a juggernaut at Folsom High, he was lured back to the college game at Eastern Washington last year at the age of 47, with a big assist from Washington coach Chris Petersen.

It’s ironic that he would wind up at Utah because it was the Utes who inspired him to overhaul his offensive philosophy. His Folsom teams were 15-15 after his first three seasons and going nowhere with the West Coast offense. They ranked 158th, 32nd and 48th in passing yards among California teams, respectively. Then he saw Urban Meyer’s spread offense on TV in 2004 and had an epiphany. He immediately converted his West Coast offense to the spread. It took a couple of years of tweaking and then Taylor’s offense took off.

During the next seven seasons (2009-2015) Folsom ranked among the state’s top five every year in passing yardage, leading the state four years in a row. The Bulldogs were 58-3 during that stretch and won two state championships while his quarterback, Jake Browning, threw for a preposterous 16,775 yards and 229 touchdown passes — both state records. As a senior he threw for 5,790 yards and a national record-tying 91 touchdowns despite rarely playing in the fourth quarter because of the lopsided scores. Browning led Washington to the national playoffs last season.

Fred Whittingham, a Ute assistant coach and brother of the head coach, discovered Taylor several years ago. He was in the publishing business and living in California at the time, and his children attended Folsom High. During a career day at Folsom he spoke to a class taught by Taylor. Whittingham didn’t even know that Taylor was a coach until they fell into a long conversation after the class.

“It became apparent he knew a lot about football,” says Fred Whittingham. “I remember thinking that the way he speaks and articulates his offensive philosophy is impressive and that this was a college-caliber coach.”

Fred told his brother Kyle about Taylor — “This is a guy to keep an eye on,” he said. The brothers never spoke of Taylor again until after Kyle hired him recently, but Kyle took note.

“I watched (Tayor) from afar for three or four years,” says Kyle. “I was very intrigued. Still, you wonder how that will work at the next level.”

He soon found out. Taylor was offered the OC job at Eastern Washington last winter and the results were the same. With almost all of EWU’s offensive starters gone, he built an offense around sophomore Gage Gubrud, a walk-on quarterback who had run the Wing-T in high school. They set national FCS records for passing yards and total offense and won 12 of 14 games. Gubrud threw for 5,160 yards and 48 touchdowns, averaging nine yards per attempt. If you’re wondering how this translates to the FBS level: EWU opened the season by putting up 45 points to beat Washington State of the Pac-12.

“That was good enough for me,” says Kyle Whittingham.

For the record, Taylor is Utah’s eighth coordinator in nine years. You might reasonably wonder how it is possible that eight coordinators — many of them accomplished football men with a history of success — failed, or if the problem is systemic. To be fair, one of those OCs, Norm Chow, left the job to be a head coach.

“I want more production so we can win games,” says Whittingham. Specifically, he wants a passing attack.

Since joining the Pac-12 in 2011, the Utes have finished at the bottom of the league annually in passing yards — 12th in both 2011 and 2012, 10th in 2013, 12th again in 2014, 11th in 2015, and ninth in 2016.

They haven’t quite joined the passing era that has overtaken all of football, from high school to the NFL. As a result, they haven’t finished among the nation’s top 30 in total offense since 2005. Their national total offense rankings in the last eight years: 54th, 52nd, 109th, 107th, 76th, 76th, 97th, 51st.

And yet the Utes, with defense and a running game, have won at least eight games in nine of 11 seasons, won 10 of 11 bowl games and collected the second most wins in the Pac-12 the last three years (behind Stanford). In 2008, they ranked No. 2 in the country and beat Alabama in the Sugar Bowl and still ranked no better than 35th in total offense.

Whittingham says he has given Taylor free rein to run the offense. If that’s the case, there will be dramatic changes for an offense that has been built for running and ball control. Taylor’s no-huddle offense at EWU threw 620 passes last season (compared to Utah’s 390).

The slender, 6-foot-4 Taylor was an exceptional quarterback himself. A three-year starter at Cal, he led the Pac-10 in total offense and set school records for passing, total offense and touchdown passes. The New York Jets made him the 84th overall pick of the 1990 draft. He played two seasons, saw action in seven games and completed 12 of 20 passes for 60 yards, two touchdowns and one interception. He went to the Miami Dolphins training camp but was released again.

“I lost a little passion for it,” he says. “I could’ve hung in there and tried again — probably should have — but I decided to hang it up.”

He claims he has wanted to coach since he was 7 years old — “I was just drawn to the tactical part of it,” he says — and he prepared for it during his playing days by taking a keen interest in understanding the game. He grilled coaches with questions, studied video and filled notebooks with notes, which he still has. “I tried to learn from everyone,” he says.

While playing for Cal, he saw the long hours and lifestyle that college coaches endure and decided he would coach at the high school level instead. After leaving the NFL, he became a substitute teacher and high school football coach. That lasted one season. He and his future wife Tracy saw then-Colorado coach Rick Neuheisel on TV one night and Taylor casually mentioned that he knew the coach. She asked him if he had ever considered coaching in college. “Yeah, but I worry about the time commitment,” he replied. She told him, “You should do it now while you’re young and can move around.”

Taylor called Neuheisel and was hired as a graduate assistant. A year later the new head coach at Cal, Steve Mariucci, who had coached wide receivers at Cal when Taylor played there, hired him to coach wide receivers. A year later, Mariucci left to take the head coaching job with the San Francisco 49ers and was replaced by Tom Holmoe, who retained Taylor as a quarterbacks coach.

After six years in the college coaching ranks, Taylor decided he had had enough. He was newly married and working long hours and struggling with the high cost of living in the Bay Area. He left Cal four years later and returned to high school coaching. He was strictly a West Coast offense practitioner until he saw Meyer’s teams at Utah.

“They were lighting up defenses, putting them on their heels,” he says. “It was just their mentality. It was a bit of an epiphany for me. I thought, I gotta do that. We (Folsom) were not where I thought we should be. We were mediocre. We weren’t doing a great job of maximizing players. I don’t blame the kids. There’s always a way.”

He called Meyer after the season to pick his brain about the spread offense. He spent four days in Las Vegas visiting with Meyer’s former OC at Utah, Mike Sanford, who was now the head coach at UNLV. During the next few years he visited spread coaches at Washington State, Oregon, Arizona, Cal and Boise State. And then he made the offense his own. He started a football class at Folsom, which provided him an opportunity to teach the offense to his players while also serving as his laboratory, a place where he could try new ideas on the dry-erase board. He came up with new wrinkles for the offense and new ways to teach it.

“It was polishing and tweaking,” he says.

He was so successful that college coaches became curious about what he was doing. One of them was Petersen, who was coaching Boise State at the time. He came to watch Browning, but he stayed after practice to grill Taylor with questions. He wanted to know his philosophy of coaching quarterbacks. They talked for 90 minutes. The next day Petersen called and invited him to talk to his quarterbacks at a clinic in Boise. After the clinic, Taylor mentioned to Petersen that he was considering a return to the college game. When EWU head coach Beau Baldwin began searching for an offensive coordinator, Petersen called him and told him about Taylor. Baldwin flew to California to meet with Taylor and hired him the next day.

It was a bold move for both coaches. Baldwin was hiring a coach straight out of high school to run his offense. Taylor was taking a 50 percent pay cut. He didn’t make much as a high school teacher, but he owned and operated lucrative quarterback schools around the state and further augmented his income as a TV color analyst for Cal football. He had to give up both jobs per NCAA rules. He sold his house and moved his wife and three children to Cheney, Washington. A few months later they moved to Salt Lake City and a new job.

“It’s been crazy,” says Taylor of the dramatic turn his life has taken in the last year. “I feel very fortunate to be here. In one sense, you want to smell the roses and enjoy it, but I’ve got to get focused on day-to-day improvement.”

Taylor, a genuinely affable and open man, pauses and then continues. “I absolutely feel the pressure. When you jump from one level to the next, there’s pressure to make it happen and everyone is looking at you to see if you’re the right guy. I try to stay focused and be willing to adapt. If I see something is not working, I try not to be stubborn and stick with it; I try to be open to different things … We’ve got everything we need here to be successful. If not, it’s on me.”

Email: drob@deseretnews.com