Unfortunately, leagues do not exist for wheelchair tennis. So we try to create other opportunities for our players, such as these camps – Jason Allen, manager of wheelchair and technical support for USTA

MURRAY — Rick Messer felt like a fool as he attempted to maneuver the specially made wheelchair around the tennis court.

But the 42-year-old was happy in that he has learned that while a motorcycle accident could steal his ability to walk, it couldn’t steal his desire to seek — and conquer — challenges.

“It’s a lot harder than I thought it was going to be,” the Alabama native said of participating in the All Comers Wheelchair Tennis Camp sponsored by the USTA and Utah Tennis at the Sports Mall Athletic Club this weekend. “I was over there, and I looked like a fool, just trying to make the right cuts to hit the ball. … It’s extremely difficult.”

But the man who moved to Utah so he could pursue his dream of alpine skiing in the Paralympics said he has no doubt he’ll stick with the sport that’s so new to him, he’s still learning the terminology and rules. “It’s a challenge,” he said smiling. “And I like challenges.” Messer said sports, mostly skiing, has given him normalcy after a motorcycle accident 10 years ago left him paralyzed.

“I was hating the world when I first got hurt,” he said. “My therapist said, ‘I'll figure out something to get the wind back in your face.’” She sent him to a ski camp in Colorado, and the man who’d never played sports of any kind said, “It was all downhill from there. … They couldn’t keep me from it. I became a completely different person.” Messer was one of 24 people who participated in the four-day camp that concluded Sunday. About half of them were from Utah, while the others came from New York, Idaho and Georgia.

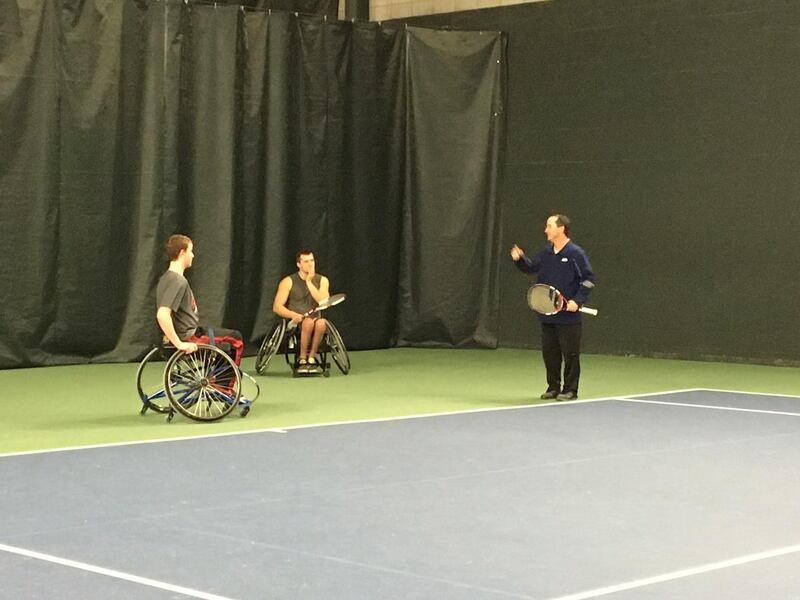

The purpose of the camp ranges from an introduction to the sport to allowing the U.S. national team coaches to find promising young talent.

“Unfortunately, leagues do not exist for wheelchair tennis,” said Jason Allen, manager of wheelchair and technical support for USTA. “So we try to create other opportunities for our players, such as these camps.”

Wheelchair tennis does, however, have a professional tour, and it is a Paralympic sport. The number of wheelchair tennis players is tough to know because the official count — 600 — comes from USTA sanctioned tournaments or events.

“We know that number is incorrect because a lot of people don’t play tournaments,” Allen said. “So we say there are probably around 1,300 people nationwide playing wheelchair tennis.”

Laurie Lambert of Utah Tennis organized the camp, which is about seven years old. She said the camp is just one of the local offerings for wheelchair tennis players.

“We try and get our wheelchair players out in the public playing in able-bodied tournaments and able-bodied leagues,” she said. “So more able-bodied people see them, and they might have friends or know someone who is in a chair.” Utah Tennis officials see hosting the camp as an opportunity to increase local opportunities.

“I think it’s just to make them love the sport even more,” Lambert said. “I mean, they definitely will be better tennis players at the end of the weekend. But just to connect them to each other, to love the sport and to want to keep playing year round.” Currently, Utah Tennis offers 52 weeks of wheelchair programing year-round that is free to all players. It all has junior camps and clinics about 24 weeks of the year.

“Our goal is just to grow,” she said. “We’re not talking hundreds of people, but if we grow two or three juniors and three adults a year, that’s success. We have about 100 (local) players on our email list.”

Most of those are in Salt Lake City, but certainly not all.

Nathan Hunter, who was born with spina bifida, is a sophomore at Grantsville High, and he’s one of two high school players participating in the camp.

“I tried able-bodied baseball and tennis, and my knees just started to wear down,” Hunter said. “I tried to find other opportunities, and in 2009-10, my parents found this. I’ve been hooked ever since.” Hunter competes with and against able-bodied athletes on Grantsville’s tennis team, which he said can be difficult.

While most of the rules are the same, the biggest difference is that wheelchair athletes get two bounces to return a ball, while able-bodied players get one bounce. That extra bounce, Hunter said, can give an opponent more time to get in position, while the opposite is true for him.

Still, he said playing with able-bodied athletes is making him a better player.

“I don’t think I would be as good as I am,” he said, noting he has coaches and teammates willing to play with him. “I discover for myself what I need to work on.”

Hunter dreams of playing in the Paralympics, and that dream became a bit more realistic when he met David Wagner at this weekend’s camp.

The 42-year-old is the most decorated wheelchair tennis player in history with eight Paralympic medals and 18 grand slam titles, and he’s coaching at this weekend’s event. He said it was a camp like this that helped him rekindle a passion for tennis he’d discovered just 10 months before a surfing accident left him paralyzed.

“I learned right away that there were a lot of options out there,” he said. “It absolutely helps. I mean, if you weren’t an athlete before you got hurt, just because you sit in a chair doesn’t mean you’re going to sit down and be an athlete.” Still, he said, whatever you love, you can find a way to do it if you’re willing to be creative.

“You might have to adapt something, change something to make it fit your disability,” he said. “But you can still do all of the same things.”

Jason Allen said the Utah camp is so successful, they’d like to replicate the model across the country.

“We do three of these All Comers camps a year, and we’d like the others to fall in line with the quality of this camp,” he said. “The amount of players, the level of coaching, they’re also very fiscally responsible with the money we give them. The players have a great time, so we want to duplicate this model throughout the country. We’d like to see over the next year and a half an increase from three camps to six nationwide. This is a developmental training ground for our next Paralympians and our pro tour.”

Wagner knows his success might inspire some of the athletes at the camp, but for him, it's as much about the first-time player who may only use the sport as a way to have fun with family or friends.

“It’s just great to see somebody for the first time get into a sports chair,” he said, relating a story about how Messer questioned the tilt in the wheels of a tennis chair. “And then he got out there and he made his first turn and hit his first ball, and he had the biggest grin on his face. It’s like, that’s what this is all about. Just having somebody who didn’t even know this was possible, to be able to do that, it’s awesome to be involved in something like that.”