SALT LAKE CITY — When Kathleen Lopez left her abusive relationship, she took only a diaper bag and her 8-month-old son. The baby gave her the courage to leave; it seemed inevitable the abuse would spill on to him if she stayed. In the middle of the night, they went to a battered-women’s shelter.

She felt like it took her a long time to work up courage to leave, though it was months, not years. She endured threats and apologies and then more abuse before making that escape more than 30 years ago, said Lopez, now 52, owner and CEO of Sentinel Sales & Management in American Fork, Utah.

Kathleen Lopez at her American Fork offices on Tuesday, Aug. 1, 2017. | Scott G Winterton, Deseret News

“I was young and naïve,” she said of that painful time in her life. “Early, I was in love and not able to process the red flags, though they were there.”

People experiencing domestic abuse feel like they’re all alone, although that’s far from true. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence says on average 20 people are abused by an intimate partner in America every minute — about 10 million women and men a year. One-third of women and one-fourth of men experience some form of physical violence by a partner within their lifetime. On a typical day, there are more than 20,000 phone calls placed to domestic violence hotlines nationwide.

Domestic abuse is a societal problem that has achieved an especially high media profile this summer in Utah with the death of several women as the result of domestic abuse, including most recently a Utah woman allegedly killed by her husband while the family was on a cruise. Earlier this summer, a mother and one of her sons were gunned down by a man she'd dated, who then killed himself.

Experts say victims of domestic violence ask themselves how they could have prevented the abuse and what might have helped them recognize it sooner, before it — and the relationship — became entrenched. Even if they do recognize it early, they may wonder what to do.

The answers to such seemingly straightforward questions are complex for those trying to carefully pick their way through the landmine of intimate-partner abuse.

Lopez hadn’t been raised in an abusive home. She didn’t know what it was at first, or how to handle it. “It can be a slow process recognizing it and a lot of psychological abuse can happen before it becomes physical abuse,” she told the Deseret News.

Kathleen Lopez at her American Fork offices on Tuesday, Aug. 1, 2017. | Scott G Winterton, Deseret News

What’s happening to me?

Many factors prevent people from recognizing early signs that someone is or will become abusive to an intimate partner.

“People forget that it didn’t start bad: a date, a dinner, let me get your coat and hit you in the face,” said Stephanie Nilva, who runs Day One, a group in New York City committed to preventing dating and domestic abuse. “It is good in the beginning and people love each other. Things that can become abusive can be mistaken for intense attraction and obsession.”

That early intense attraction can be a warning sign, too. When someone you’ve been dating for two weeks wants you to himself, “flattering and disturbing get mixed up,” she said.

A partner who lies, is jealous of your family and friends, acts possessive, blames others for his or her own behavior, wants to know where you are or who you’re with, tries to move the relationship forward too quickly, doesn’t want to introduce you to his family and friends, criticizes or blows up gives off red flags that shouldn’t be ignored, said Angela McIlveen, a family law attorney in Gastonia, North Carolina.

Self-awareness early in a relationship is a good prevention tool. If a relationship makes you feel uneasy, unsafe, anxious, judged or blamed, it’s not a relationship to pursue. And once kids and pets and shared finances are part of the picture, it’s much harder to extricate oneself, said psychologist Jude Miller Burke of Phoenix, author of “The Adversity Advantage: Turn Your Childhood Hardship into Career and Life Success.”

When abuse feels familiar, it's also hard to spot. Someone who grew up in a turbulent household may not know what a healthy relationship looks like, thinking it happens in all relationships. Those who haven’t had relationship experience may not have anything to compare it to, so they don’t see belittling, isolating or even slapping as aberrant. That pattern can be perpetuated from generation to generation, putting one’s children at risk, too.

Adverse childhood experiences (called ACEs in research), including domestic abuse and seeing a parent treated badly during one’s childhood, may create lifetime risk factors. The more ACEs a child accumulates, the greater the risk of suicide, homelessness, criminal justice involvement, chronic health problems and falling victim to domestic abuse or possibly becoming abusive as an adult.

What is probably the biggest barrier to spotting potential for abuse early on, though, is an abuser typically hides behind a façade of public charm, said Nancy Virden, a mental health and recovery advocate and founder of Always the Fight Ministries in Cleveland. “Abusers believe they are right and entitled to admiration. Publicly, they present as put-together, fit into the environment around them and often pass as the nicest, if not the most honest, guy in the room.”

That charm makes it easy to court someone. Virden says it may morph into power and control over a partner.

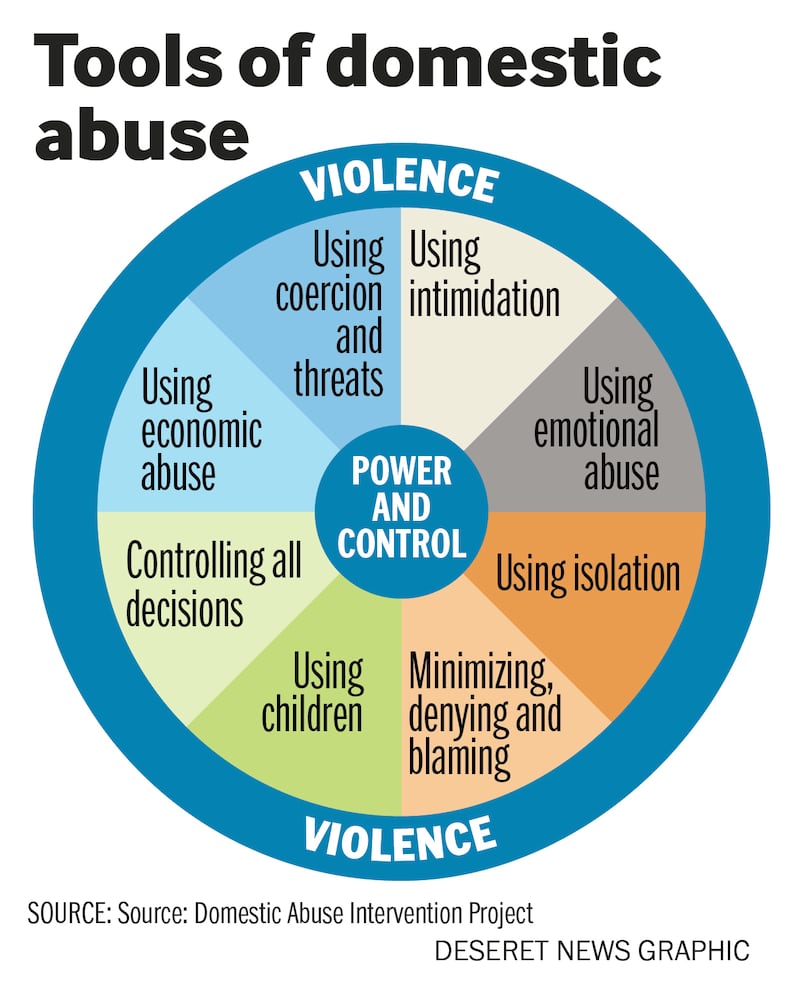

Domestic violence happens across a spectrum with various “real and dangerous” types of abuse, not just obvious, outright violence, said Jenn Oxborrow, executive director of the Utah Domestic Violence Coalition. In most cases, the victim is a woman, the abuser a man, but that can be reversed and abuse also sometimes occurs in same-sex relationships.

When a partner puts down people you love or your career or your passions, it shouldn’t be brushed off, she warned. “There are many early warning signs of abuse that can escalate pretty quickly. You need to get out,” she said. Any dynamic in a relationship that gives one person power and control over the other is abusive, she added.

Burke lists a “lack of sympathy” as another red flag that someone might be or become abusive.

Someone who sees early red flags should hit the brakes or at least slow things down until issues are resolved. Once abuse starts, “you need to go to your own counselor — and only one who is an expert with anger management and domestic violence.” Not all counselors and therapists understand the dynamics of domestic violence or what to do about it.

Recognizable patterns

While it may be hard to spot the warning signs and details vary between couples, the pattern of domestic violence is predictable. After an abusive incident, “the cycle of domestic abuse includes apologies and excuse-making,” Virden said. “A spouse who believes this so-called repentance will also apologize and excuse the abuse. It can take a long time to realize it’s an unending pattern.”

If abuse was obvious early on, people would leave before they were fully invested in a shared life. But it’s never that straightforward. Initially, bad behavior is blamed on a bad day or too much stress or a rough patch at work, for example.

“You see this cycle once, you’ll probably see it twice. You see it twice, I guarantee you are going to see it a third time,” said Jennifer Ponce, prevention education manager from Laura’s House, a domestic violence agency in Ladera Ranch, California. “It’s so dangerous. Little by little, that honeymoon phase starts disappearing.”

Ponce said it takes an average of seven times before someone actually leaves an established abusive relationship.

That number would not surprise Susan, a Salt Lake area woman who met her husband when both were in their late 20s; she’s now in her early 60s and asked that her real name not be used.

Her husband wore a tie, worked every day and was even somewhat chivalrous in manner. The first inkling she had of his temper occurred when one of his dogs got loose. He dragged it home and threw it down the stairs. When she objected, he apologized and said he was just upset.

"I could have said, 'That’s a sign. Steer clear.' I didn’t. I was in love," she said.

She married him. Once, they were teasing each other as they hiked and he pushed her “a little hard.” She thought it odd, but didn’t dwell on it.

Fast forward five years. They had a child. They had a good life. But he got really upset when their water bed broke. She helped him clean it up and made up the foldaway in the den. Later, lying there, she said, “You were so angry. I’ve never seen you like that. What was the deal?” It would be the first of several times over decades of marriage that he punched her.

A couple of friends in whom she confided told her that such abuse was so out of character for him. She realized they weren’t sure if they believed her. She healed physically and kind of wished it away, embarrassed and unsure how to address it. “He seldom said sorry. He barely acknowledged it happened.”

She was careful not to set him off, as if it was her problem, and they went on. “When I kept it private between the two of us, I became a co-conspirator,” she said. When the kids were grown, she left. She convinced herself her children didn’t know what was going on until later. She's not sure it's true, though. Between the incidents, the couple had “built a good life together, including community relationships, a nice house, the trappings of success."

When she left, he gave her an embrace: “We did a good job,” he told her. “We lasted a long time.”

The problem, as Susan sees it, is the person being abused often doesn’t know what’s normal in a relationship. “If I were to counsel anyone, I would say that when you question whether something’s OK or not, it’s really not OK. If you want a relationship to last, you have to deal with it as soon as possible.”

Bucking perception

Even individuals who figure out that their relationships are unhealthy struggle with what to do next. When an abused person confides in friends or seeks help, it’s not uncommon to be disbelieved, as Susan was. Shared friends are doubtful and sometimes dismissive, experts say, because the abuser’s charming façade is convincing and the victim may seem nervous, scattered, even untruthful. Virden said the problem extends beyond the circle of friends and family to religious leaders, even marriage counselors and in court.

Oxborrow tells what happened to a woman whose partner had stabbed and strangled her. In court, she kept laughing. “People not working with domestic violence might not understand that,” said Oxborrow. “It’s a limbic response to trauma. She was not in control of that response. She certainly didn’t think it was funny. It was her nervous reaction to being in the same room with him."

Couples counseling is largely ineffective for that very reason — the person “in control” may be able to manipulate perceptions in that setting, too. Experts say counseling is important, but the abuse victim needs to find an expert trained in domestic violence and get individual help.

The more signs of abuse there are, the more important safety planning becomes with a trained victim advocate. Even when one is not ready to leave the relationship, someone trained in domestic violence can help plan. Well-meaning friends may actually make things worse, said Oxborrow, who noted, “When we help someone plan by telling them to go to a friend or neighbor, in fact we could be putting that person at risk, too.”

Experts know that domestic violence is a complicated crime, she said. It’s not like being hit by a drunk driver or experiencing a bank robbery. “Those are random things. This is intentional, done by someone you’ve known and loved and trusted who is using that love and trust for personal gain and control. It’s complex psychologically. Working with a trained victim advocate who understands the complexity of that is really important to get survivors engaged in planning for their own safety.”

Most communities have trained victim advocates to help someone navigate to safety. They’ve worked with trauma survivors. They know how to help with emergency shelter, emergency child care and later housing. They know what it takes to heal and recover, Oxborrow said.

Before it starts

Day One, Nilva’s New York City group, aims for prevention. It works with teens to stop dating abuse and domestic violence through a combination of education, support services, legal advocacy and leadership development.

Nilva and others talk to adolescents in middle and high school about what a healthy relationship looks like. They pick apart what jealousy is and how to respond to it. That early learning is the best way to avoid perpetrating or enduring an abusive relationship, she said.

They tell young people it’s not appropriate that someone wants to check your phone to see who you’ve been talking to. It’s not all right when someone gets mad or abusive because you didn’t answer a text quick enough. The kids learn to spot blame shifting and irrational behavior.

They’re not just trying to help young people recognize warnings for abuse in relationships; they also hope education can stop young people from growing into perpetrators by teaching them how to have healthy relationships. Patterns become more entrenched with adults and Nilva said efforts to treat batterers are “disheartening,” compared to prevention.

California-based Laura’s House has a teen program that’s all about healthy relationships and abuse prevention, “so kids know what’s normal,” too. "The goal is to arm kids so in relationships they recognize red flags immediately for verbal, psychological, financial and physical abuse,” said Ponce.

If they aren’t sure, teens learn they can talk to someone trained in domestic violence, “someone like me who can lay out what a relationship should look like,” Ponce said.

They teach the elements of a healthy relationship: love, trust, respect and safety. “If at any point you don’t feel loved, you don’t feel trusted, you don’t feel respected and safe, those are the times you can start planning to leave. And those are what you should be looking for in a relationship,” Ponce said.

“What is important for victims to know is that there is the other side” of abuse, said Virden. “Myriads of people have been there and will walk a survivor through all the painful mess.”

Individuals in an abusive relationship can get free, confidential help and support, as can domestic violence survivors, by calling 1-800-897-5465 or by visiting udvc.org.